Everyone loves watching a good film albeit at the cinema or at home on the television etc. With a collection of over 1000 DVDs that includes a LOT of films, it is clear to see that this is another big passion of mine.

I can’t remember the very first film I went to see at the pictures but it was in the mid-1970’s and it possibly could have been the Disney animation adaptation of Robin Hood. Visits to the cinema over the decades as a child and older, with family have always held special memories for me.

Watching a film on the telly is always good but nothing beats the experience and sound quality of watching it on the big screen. Having a home cinema has always been a dream of mine but that probably won’t ever happen but one day I would like to get a decent surround sound system and projector with a large screen or a large telly to watch films on. I will say never say never on that one!

I like most film genres with my favourite being Horror and Science Fiction ones. I have favourite actors and actresses the same as anyone else does and they will be shown on this page. I am not going to list every film I have watched in my lifetime, that would be IMPOSSIBLE to remember but I will list films I have watched and enjoyed that I think are worth watching for someone else but of course, your opinions may differ from mine, that’s life.

About Film

A film, also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay, or flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmosphere through the use of moving images. Flick is, in general, a slang term, first recorded in 1926. It originates in the verb flicker, owing to the flickering appearance of early films. These images are generally accompanied by sound and, more rarely, other sensory stimulations. The word cinema, short for cinematography, is often used to refer to filmmaking and the film industry, and the art form that is the result of it.

The History Of Film

Precursors

The art of film has drawn on several earlier traditions in fields such as oral storytelling, literature, theatre, and visual arts. Forms of art and entertainment that have already featured moving or projected images include shadowgraphy (probably used since prehistoric times), camera obscura (a natural phenomenon that has possibly been used as an artistic aid since prehistoric times), shadow puppetry (possibly originated around 200 BCE in Central Asia, India, Indonesia or China) and the magic lantern (developed in the 1650’s, this multi-media phantasmagoria shows that magic lanterns were popular from 1790 throughout the first half of the 19th century and could feature mechanical slides, rear projection, mobile projectors, superimposition, dissolving views, live actors, smoke that was sometimes used to project images upon, odours, sounds, and even electric shocks).

Before Celluloid

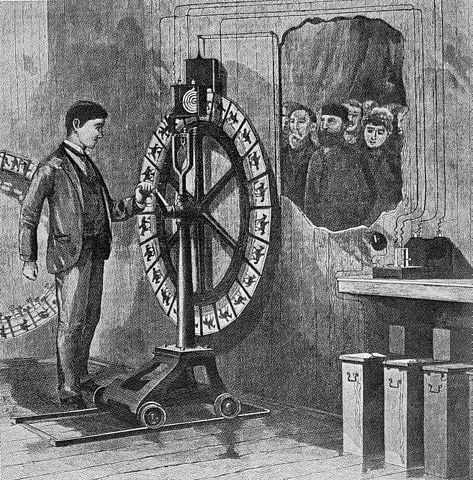

The stroboscopic animation principle was introduced in 1833 with the stroboscopic disc (better known as the phenakisticope) and later applied in the zoetrope (since 1866), the flip book (since 1868), and the praxinoscope (since 1877) before it became the basic principle for cinematography.

Prof. Stampfer’s Stroboscopische Scheibe No. X., created on the 22nd of June, 1833. This is side Nr. 10 of the reworked second series of Stampfer’s stroboscopic disc published by Trentsensky & Vieweg in the same year.

Experiments with early phenakisticope-based animation projectors were made at least as early as 1843 and publicly screened in 1847. Jules Duboscq marketed phenakisticope projection systems in France from circa 1853 until the 1890’s.

Photography was introduced in 1839, but initially, photographic emulsions needed such long exposures that the recording of moving subjects seemed impossible. At least as early as 1844, a photographic series of subjects posed in different positions was created to either suggest a motion sequence or document a range of different viewing angles. The advent of stereoscopic photography, with early experiments in the 1840’s and commercial success since the early 1850’s, raised interest in completing the photographic medium with the addition of means to capture colour and motion. In 1849, Joseph Plateau published the idea to combine his invention of the phenakisticope with the stereoscope, as suggested to him by stereoscope inventor Charles Wheatstone, and to use photographs of plaster sculptures in different positions to be animated in the combined device. In 1852, Jules Duboscq patented such an instrument as the Stereoscope-fantascope, ou Bioscope, but he only marketed it very briefly, without success. One Bioscope disc with stereoscopic photographs of a machine is in the Plateau collection of Ghent University, but no instruments or other discs have yet been found.

By the late 1850’s the first examples of instantaneous photography came about and provided hope that motion photography would soon be possible, but it took a few decades before it was successfully combined with a method to record a series of sequential images in real-time. In 1878, Eadweard Muybridge eventually managed to take a series of photographs of a running horse with a battery of cameras in a line along the track and published the results as The Horse in Motion on cabinet cards. Muybridge, as well as Etienne-Jules Marey, Ottomar Anschütz, and many others, would create many more chronophotography studies. Muybridge had the contours of dozens of his chronophotographic series traced onto glass discs and projected them with his zoopraxiscope in his lectures from 1880 to 1895.

An animation of the retouched Sallie Garner card from The Horse in Motion series by Eadweard Muybridge. The series was from 1878 – 1879.

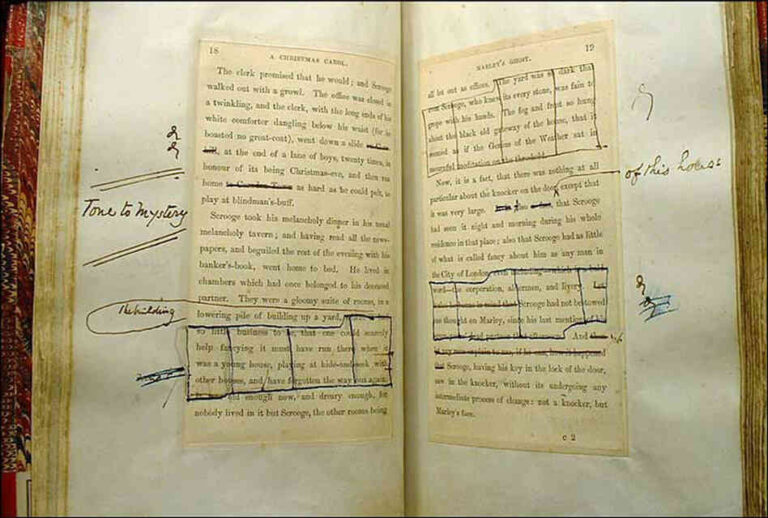

Anschutz made his first instantaneous photographs in 1881. He developed a portable camera that allowed shutter speeds as short as 1/1000 of a second in 1882. The quality of his pictures was generally regarded to be much higher than that of the chronophotography works of Muybridge and Etienne-Jules Marey. In 1886, Anschutz developed the Electrotachyscope, an early device that displayed short motion picture loops with 24 glass plate photographs on a 1.5-meter-wide rotating wheel that was hand-cranked to the speed of circa 30 frames per second. Different versions were shown at many international exhibitions, fairs, conventions, and arcades from 1887 until at least 1894. Starting in 1891, some 152 examples of a coin-operated peep-box Electrotachyscope model were manufactured by Siemens & Halske in Berlin and sold internationally. Nearly 34,000 people paid to see it at the Berlin Exhibition Park in the summer of 1892. Others saw it in London or at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. On the 25th of November 1894, Anschutz introduced an Electrotachyscope projector with a 6 x 8 meter screening in Berlin. Between the 22nd of February and the 30th of March 1895, a total of circa 7,000 paying customers came to view a 1.5-hour show of some 40 scenes at a 300-seat hall in the old Reichstag building in Berlin.

A picture of Ottomar’s Anschutz’s electrotachyscope, first published in Scientific American on the 16th of November, 1889.

Emile Reynaud already mentioned the possibility of projecting the images of the Praxinoscope in his 1877 patent application. He presented a praxinoscope projection device at the Societe Francaise de Photographie on the 4th of June 1880 but did not market his praxinoscope before 1882. He then further developed the device into the Theatre Optique which could project longer sequences with separate backgrounds, patented in 1888. He created several movies for the machine by painting images on hundreds of gelatin plates that were mounted into cardboard frames and attached to a cloth band. From the 28th of October 1892 to March 1900 Reynaud gave over 12,800 shows to a total of over 500,000 visitors at the Grevin Museu in Paris.

First Motion Pictures

By the end of the 1880’s, the introduction of lengths of celluloid photographic film and the invention of motion picture cameras, which could photograph a rapid sequence of images using only one lens, allowed the action to be captured and stored on a single compact reel of film.

Movies were initially shown publicly to one person at a time through peep show devices such as the Electrotachyscope, Kinetoscope, and the Mutoscope. Not much later, exhibitors managed to project films on large screens for theatre audiences.

The first public screenings of films at which admission was charged were made in 1895 by the American Woodville Latham and his sons, using films produced by their Eidoloscope company, by the Skladanowsky brothers, and by the arguably better known French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumiere with ten of their own productions. Private screenings had preceded these by several months, with Latham’s slightly predating the others.

Roundhay Garden Scene is a short silent motion picture filmed by French inventor Louis Le Prince at Oakwood Grange in Roundhay, Leeds, in northern England on the 14th of October 1888.

Pauvre Pierrot or Poor Pete as it is known in English is a French short animated film directed by Charles-Emile Reynaud in 1891 and was released in 1892.

Georges Melies’ Le Voyage dans la Lune or A Trip to the Moon as it is known in English is an early narrative film and also an early science fiction film, released in 1902.

The Bond is a two-reel propaganda film created by Charlie Chaplin at his own expense for the Liberty Loan Committee to help sell U.S. Liberty Bonds during World War I, released in 1918.

Early Evolution

The earliest films were simply one static shot that showed an event or action with no editing or other cinematic techniques. Typical films showed employees leaving a factory gate, people walking in the street, and the view from the front of a trolley as it traveled a city’s Main Street. According to legend, when a film showed a locomotive at high speed approaching the audience, the audience panicked and ran from the theater. Around the turn of the 20th century, films started stringing several scenes together to tell a story. The filmmakers who first put several shots or scenes discovered that, when one shot follows another, that act establishes a relationship between the content in the separate shots in the minds of the viewer. It is this relationship that makes all film storytelling possible. In a simple example, if a person is shown looking out a window, whatever the next shot shows, it will be regarded as the view the person was seeing. Each scene was a single stationary shot with the action occurring before it. The scenes were later broken up into multiple shots photographed from different distances and angles. Other techniques such as camera movement were developed as effective ways to tell a story with film. Until sound film became commercially practical in the late 1920’s, motion pictures were purely visual art, but these innovative silent films had gained a hold on the public imagination. Rather than leave audiences with only the noise of the projector as an accompaniment, theater owners hired a pianist or organist or, in large urban theaters, a full orchestra to play music that fit the mood of the film at any given moment. By the early 1920’s, most films came with a prepared list of sheet music to be used for this purpose, and complete film scores were composed for major productions.

The rise of European cinema was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, while the film industry in the United States flourished with the rise of Hollywood, typified most prominently by the innovative work of D. W. Griffith in The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916). However, in the 1920’s, European filmmakers such as Eisenstein, F. W. Murnau, and Fritz Lang, in many ways inspired by the meteoric wartime progress of film through Griffith, along with the contributions of Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and others, quickly caught up with American film-making and continued to further advance the medium.

Sound

In the 1920’s, the development of electronic sound recording technologies made it practical to incorporate a soundtrack of speech, music, and sound effects synchronized with the action on the screen. The resulting sound films were initially distinguished from the usual silent moving pictures or movies by calling them talking pictures or talkies. The revolution they wrought was swift. By 1930, silent film was practically extinct in the US and already being referred to as the old medium.

The evolution of sound in cinema began with the idea of combining moving images with existing phonograph sound technology. Early sound-film systems, such as Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope and the Vitaphone used by Warner Bros., laid the groundwork for synchronized sound in film. The Vitaphone system, produced alongside Bell Telephone Company and Western Electric, faced initial resistance due to expensive equipping costs, but sound in cinema gained acceptance with movies like Don Juan (1926) and The Jazz Singer (1927).

American film studios, while Europe standardized on Tobis-Klangfilm and Tri-Ergon systems. This new technology allowed for greater fluidity in film, giving rise to more complex and epic movies like King Kong (1933).

As the television threat emerged in the 1940’s and 1950’s, the film industry needed to innovate to attract audiences. In terms of sound technology, this meant the development of surround sound and more sophisticated audio systems, such as Cinerama’s seven-channel system. However, these advances required a large number of personnel to operate the equipment and maintain the sound experience in cinemas.

In 1966, Dolby Laboratories introduced the Dolby A noise reduction system, which became a standard in the recording industry and eliminated the hissing sound associated with earlier standardization efforts. Dolby Stereo, a revolutionary surround sound system, followed and allowed cinema designers to take acoustics into consideration when designing cinemas. This innovation enabled audiences in smaller venues to enjoy comparable audio experiences to those in larger city cinemas.

Today, the future of sound in film remains uncertain, with potential influences from artificial intelligence, remastered audio, and personal viewing experiences shaping its development. However, it is clear that the evolution of sound in cinema has been marked by continuous innovation and a desire to create more immersive and engaging experiences for audiences.

Colour

A significant technological advancement in the film industry was the introduction of natural colour, where colour was captured directly from nature through photography, as opposed to being manually added to black-and-white prints using techniques like hand-coloring or stencil-coloring. Early colour processes often produced colours that appeared far from natural. Unlike the rapid transition from silent films to sound films, colour’s replacement of black-and-white happened more gradually.

The crucial innovation was the three-strip version of the Technicolor process, first used in animated cartoons in 1932. The process was later applied to live-action short films, specific sequences in feature films, and finally, to an entire feature film, Becky Sharp, in 1935. Although the process was expensive, the positive public response, as evidenced by increased box office revenue, generally justified the additional cost. Consequently, the number of films made in color gradually increased year after year.

The 1950’s: The Growing Influence Of Television

In the early 1950’s, the proliferation of black-and-white television started seriously depressing North American cinema attendance. In an attempt to lure audiences back into cinemas, bigger screens were installed, widescreen processes, polarised 3D projection, and stereophonic sound were introduced, and more films were made in colour, which soon became the rule rather than the exception. Some important mainstream Hollywood films were still being made in black-and-white as late as the mid-1960’s, but they marked the end of an era. Colour television receivers had been available in the U.S. since the mid-1950’s, but at first, they were very expensive and few broadcasts were in colour. During the 1960’s, prices gradually came down, colour broadcasts became common, and sales boomed. The overwhelming public verdict in favour of colour was clear. After the final flurry of black-and-white films had been released in mid-decade, all Hollywood studio productions were filmed in colour, with the usual exceptions made only at the insistence of star filmmakers such as Peter Bogdanovich and Martin Scorsese.

The 1960’s And Later

The decades following the decline of the studio system in the 1960’s saw changes in the production and style of film. Various New Wave movements (including the French New Wave, New German Cinema wave, Indian New Wave, Japanese New Wave, New Hollywood, and Egyptian New Wave) and the rise of film-school-educated independent filmmakers contributed to the changes the medium experienced in the latter half of the 20th century. Digital technology has been the driving force for change throughout the 1990’s and into the 2000’s. Digital 3D projection largely replaced earlier problem-prone 3D film systems and has become popular in the early 2010’s.

Salah Zulfikar, one of the most popular actors in the golden age of Egyptian Cinema.

Etymology And Alternative Terms

The name film originally referred to the thin layer of photochemical emulsion on the celluloid strip that used to be the actual medium for recording and displaying motion pictures.

The most common term in Europe is film while in the United States, movie is preferred.

Archaic terms include animated pictures and animated photography. Common terms for the field, in general, include the big screen, the silver screen, the movies, and cinema. The last of these is commonly used, as an overarching term, in scholarly texts and critical essays. In the early years, the word sheet was sometimes used instead of screen.

Recording And Transmission Of The Film

The moving images of a film are created by photographing actual scenes with a motion-picture camera, by photographing drawings or miniature models using traditional animation techniques, by means of C.G.I. and computer animation, or by a combination of some or all of these techniques, and other visual effects.

Before the introduction of digital production, a series of still images were recorded on a strip of chemically sensitised celluloid (photographic film stock), usually at a rate of 24 frames per second. The images are transmitted through a movie projector at the same rate as they were recorded, with a Geneva drive ensuring that each frame remains still during its short projection time. A rotating shutter causes stroboscopic intervals of darkness, but the viewer does not notice the interruptions due to flicker fusion. The apparent motion on the screen is the result of the fact that the visual sense cannot discern the individual images at high speeds, so the impressions of the images blend with the dark intervals and are thus linked together to produce the illusion of one moving image. An analogous optical soundtrack (a graphic recording of the spoken words, music, and other sounds) runs along a portion of the film exclusively reserved for it and is not projected.

Contemporary films are usually fully digital through the entire process of production, distribution, and exhibition.

Film Theory

Film theory seeks to develop concise and systematic concepts that apply to the study of film as art. The concept of film as an art-form began in 1911 with Ricciotto Canudo’s manifest The Birth of the Sixth Art. The Moscow Film School, the oldest film school in the world, was founded in 1919, in order to teach about and research film theory. Formalist film theory, led by Rudolf Arnheim, Bela Balazs, and Siegfried Kracauer, emphasized how film differed from reality and thus could be considered a valid fine art. Andre Bazin reacted against this theory by arguing that film’s artistic essence lay in its ability to mechanically reproduce reality, not in its differences from reality, and this gave rise to realist theory. More recent analysis spurred by Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalysis and Ferdinand de Saussure’s semiotics among other things has given rise to psychoanalytic film theory, structuralist film theory, feminist film theory, and others. On the other hand, critics from the analytical philosophy tradition, influenced by Wittgenstein, try to clarify misconceptions used in theoretical studies and produce analysis of a film’s vocabulary and its link to a form of life.

The Bolex H16 Reflex camera.

Language

Film is considered to have its own language. James Monaco wrote a classic text on film theory, titled How to Read a Film, that addresses this. Director Ingmar Bergman famously said, “Andrei Tarkovsky for me is the greatest director, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.” An example of the language is a sequence of back and forth images of one speaking actor’s left profile, followed by another speaking actor’s right profile, then a repetition of this, which is a language understood by the audience to indicate a conversation. This describes another theory of film, the 180-degree rule, as a visual story-telling device with an ability to place a viewer in a context of being psychologically present through the use of visual composition and editing. The Hollywood style includes this narrative theory, due to the overwhelming practice of the rule by movie studios based in Hollywood, California, during film’s classical era. Another example of cinematic language is having a shot that zooms in on the forehead of an actor with an expression of silent reflection that cuts to a shot of a younger actor who vaguely resembles the first actor, indicating that the first person is remembering a past self, an edit of compositions that causes a time transition.

Montage

Read more about Montage here.

Montage is a film editing technique in which separate pieces of film are selected, edited, and assembled to create a new section or sequence within a film. This technique can be used to convey a narrative or to create an emotional or intellectual effect by juxtaposing different shots, often for the purpose of condensing time, space, or information. Montage can involve flashbacks, parallel action, or the interplay of various visual elements to enhance the storytelling or create symbolic meaning.

The concept of montage emerged in the 1920’s, with pioneering Soviet filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein and Lev Kuleshov developing the theory of montage. Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin (1925) is a prime example of the innovative use of montage, where he employed complex juxtapositions of images to create a visceral impact on the audience.

As the art of montage evolved, filmmakers began incorporating musical and visual counterpoint to create a more dynamic and engaging experience for the viewer. The development of scene construction through mise-en-scène, editing, and special effects led to more sophisticated techniques that can be compared to those utilized in opera and ballet.

The French New Wave movement of the late 1950’s and 1960’s also embraced the montage technique, with filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut using montage to create distinctive and innovative films. This approach continues to be influential in contemporary cinema, with directors employing montage to create memorable sequences in their films.

In contemporary cinema, montage continues to play an essential role in shaping narratives and creating emotional resonance. Filmmakers have adapted the traditional montage technique to suit the evolving aesthetics and storytelling styles of modern cinema:

Rapid editing and fast-paced montages: With the advent of digital editing tools, filmmakers can now create rapid and intricate montages to convey information or emotions quickly. Films like Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream (2000) and Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Dead (2004) employ fast-paced editing techniques to create immersive and intense experiences for the audience.

Music video influence: The influence of music videos on film has led to the incorporation of stylized montage sequences, often accompanied by popular music. Films like Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) and Baby Driver (2017) use montage to create visually striking sequences that are both entertaining and narratively functional.

Sports and training montages: The sports and training montage has become a staple in modern cinema, often used to condense time and show a character’s growth or development. Examples of this can be found in films like Rocky (1976), The Karate Kid (1984), and Million Dollar Baby (2004).

Cross-cutting and parallel action: Contemporary filmmakers often use montage to create tension and suspense by cross-cutting between parallel storylines. Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010) and Dunkirk (2017) employ complex cross-cutting techniques to build narrative momentum and heighten the audience’s emotional engagement.

Thematic montage: Montage can also be used to convey thematic elements or motifs in a film. Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) employs montage to create a visual language that reflects the film’s themes of family, nostalgia, and loss.

As the medium of film continues to evolve, montage remains an integral aspect of visual storytelling, with filmmakers finding new and innovative ways to employ this powerful technique.

Film Criticism

Film criticism is the analysis and evaluation of films. In general, these works can be divided into two categories, academic criticism by film scholars and journalistic film criticism that appears regularly in newspapers and other media. Film critics working for newspapers, magazines, and broadcast media mainly review new releases. Normally they only see any given film once and have only a day or two to formulate their opinions. Despite this, critics have an important impact on the audience response and attendance at films, especially those of certain genres. Mass marketed action, horror, and comedy films tend not to be greatly affected by a critic’s overall judgment of a film. The plot summary and description of a film and the assessment of the director’s and screenwriters’ work that makes up the majority of most film reviews can still have an important impact on whether people decide to see a film. For prestige films such as most dramas and art films, the influence of reviews is important. Poor reviews from leading critics at major papers and magazines will often reduce audience interest and attendance.

The impact of a reviewer on a given film’s box office performance is a matter of debate. Some observers claim that movie marketing in the 2000’s is so intense, well-coordinated and well financed that reviewers cannot prevent a poorly written or filmed blockbuster from attaining market success. However, the cataclysmic failure of some heavily promoted films which were harshly reviewed, as well as the unexpected success of critically praised independent films indicates that extreme critical reactions can have considerable influence. Other observers note that positive film reviews have been shown to spark interest in little-known films. Conversely, there have been several films in which film companies have so little confidence that they refuse to give reviewers an advanced viewing to avoid widespread panning of the film. However, this usually backfires, as reviewers are wise to the tactic and warn the public that the film may not be worth seeing and the films often do poorly as a result. Journalist film critics are sometimes called film reviewers. Critics who take a more academic approach to films, through publishing in film journals and writing books about films using film theory or film studies approaches, study how film and filming techniques work, and what effect they have on people. Rather than having their reviews published in newspapers or appearing on television, their articles are published in scholarly journals or up-market magazines. They also tend to be affiliated with colleges or universities as professors or instructors.

In 1986, Roger Ebert, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism said, “If a movie can illuminate the lives of other people who share this planet with us and show us not only how different they are but, how even so, they share the same dreams and hurts, then it deserves to be called great.”

Industry

Read more about Industry here. Read more about World Cinema

The making and showing of motion pictures became a source of profit almost as soon as the process was invented. Upon seeing how successful their new invention, and its product, was in their native France, the Lumieres quickly set about touring the Continent to exhibit the first films privately to royalty and publicly to the masses. In each country, they would normally add new, local scenes to their catalogue and, quickly enough, found local entrepreneurs in the various countries of Europe to buy their equipment and photograph, export, import, and screen additional product commercially. The Oberammergau Passion Play of 1898 was the first commercial motion picture ever produced. Other pictures soon followed, and motion pictures became a separate industry that overshadowed the vaudeville world. Dedicated theaters and companies formed specifically to produce and distribute films, while motion picture actors became major celebrities and commanded huge fees for their performances. By 1917 Charlie Chaplin had a contract that called for an annual salary of one million dollars. From 1931 to 1956, film was also the only image storage and playback system for television programming until the introduction of videotape recorders.

In the United States, much of the film industry is centered around Hollywood, California. Other regional centers exist in many parts of the world, such as Mumbai-centered Bollywood, the Indian film industry’s Hindi cinema which produces the largest number of films in the world. Though the expense involved in making films has led cinema production to concentrate under the auspices of movie studios, recent advances in affordable film making equipment have allowed independent film productions to flourish.

Profit is a key force in the industry, due to the costly and risky nature of filmmaking; many films have large cost overruns, an example being Kevin Costner’s Waterworld. Yet many filmmakers strive to create works of lasting social significance. The Academy Awards (also known as the Oscars) are the most prominent film awards in the United States, providing recognition each year to films, based on their artistic merits (but it has got so woke lately that is questionable indeed). There is also a large industry for educational and instructional films made in lieu of or in addition to lectures and texts. Revenue in the industry is sometimes volatile due to the reliance on blockbuster films released in movie theaters. The rise of alternative home entertainment has raised questions about the future of the cinema industry, and Hollywood employment has become less reliable, particularly for medium and low-budget films.

World Cinema

Read more about World Cinema here.

World cinema is a term in film theory that refers to films made outside of the American motion picture industry, particularly those in opposition to the aesthetics and values of commercial American cinema. The Third Cinema of Latin America and various national cinemas are commonly identified as part of world cinema. The term has been criticized for Americentrism and for ignoring the diversity of different cinematic traditions around the world.

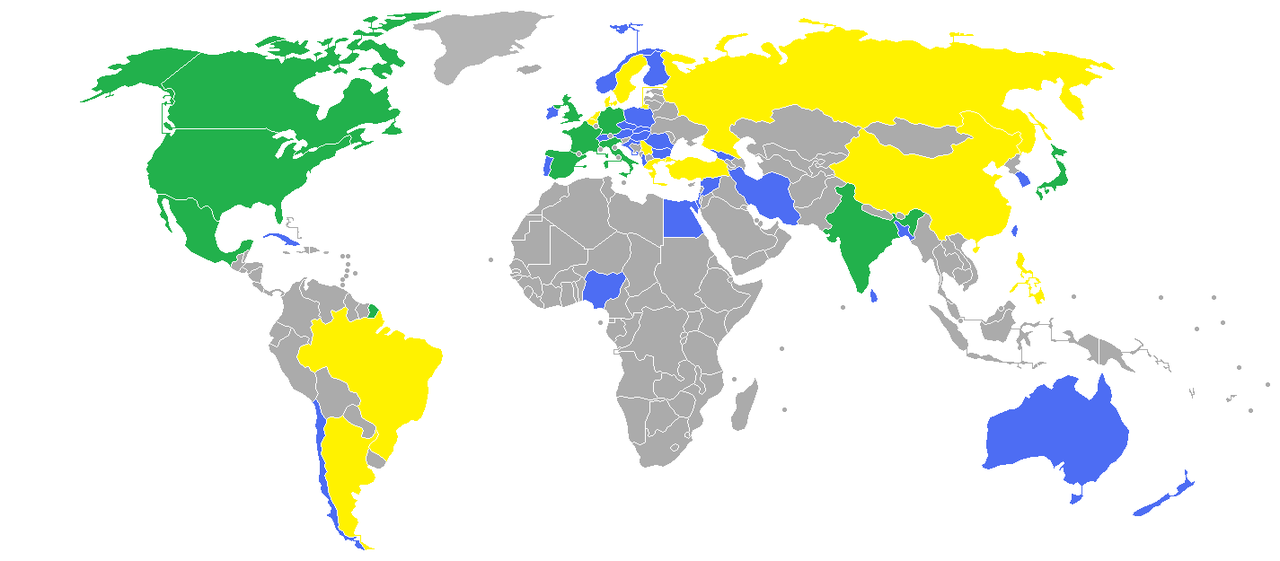

Most productive cinemas around the world based on IMDb (as of 2009). Over 10,000 titles (green), over 5,000 (yellow), over 1,000 (blue).

Associated Fields

Read more about Film theory here, Product placement here, and Propaganda here.

Derivative academic fields of study may both interact with and develop independently of filmmaking, as in film theory and analysis. Fields of academic study have been created that are derivative or dependent on the existence of film, such as film criticism, film history, divisions of film propaganda in authoritarian governments, or psychological on subliminal effects (e.g., of a flashing soda can during a screening). These fields may further create derivative fields, such as a movie review section in a newspaper or a television guide. Sub-industries can spin off from film, such as popcorn makers, and film-related toys (e.g., Star Wars figures). Sub-industries of pre-existing industries may deal specifically with film, such as product placement and other advertising within films.

Terminology

The terminology used for describing motion pictures varies considerably between British and American English. In British usage, the name of the medium is film. The word movie is understood but seldom used. Additionally, the pictures (plural) is used semi-frequently to refer to the place where movies are exhibited, while in American English this may be called the movies, but it is becoming outdated. In other countries, the place where movies are exhibited may be called a cinema or movie theatre. By contrast, in the United States, movie is the predominant form. Although the words film and movie are sometimes used interchangeably, film is more often used when considering artistic, theoretical, or technical aspects. The term movies more often refers to entertainment or commercial aspects, such as where to go for a fun evening on a date. For example, a book titled How to Understand a Film would probably be about the aesthetics or theory of film, while a book entitled Let’s Go to the Movies would probably be about the history of entertaining movies and blockbusters.

Further terminology is used to distinguish various forms and media used in the film industry. Motion pictures and moving pictures are frequently used terms for film and movie productions specifically intended for theatrical exhibition, such as, for instance, Star Wars. DVD and videotape are video formats that can reproduce a photochemical film. A reproduction based on such is called a transfer. After the advent of theatrical film as an industry, the television industry began using videotape as a recording medium. For many decades, the tape was solely an analogue medium onto which moving images could be either recorded or transferred. Film and filming refer to the photochemical medium that chemically records a visual image and the act of recording respectively. However, the act of shooting images with other visual media, such as with a digital camera, is still called filming and the resulting works are often called films as interchangeable with movies, despite not being shot on film. Silent films need not be utterly silent but are films and movies without an audible dialogue, including those that have a musical accompaniment. The word, Talkies, refers to the earliest sound films created to have audible dialogue recorded for playback along with the film, regardless of a musical accompaniment. Cinema either broadly encompasses both films and movies, or it is roughly synonymous with film and theatrical exhibition, and both are capitalised when referring to a category of art. The silver screen refers to the projection screen used to exhibit films and, by extension, is also used as a metonym for the entire film industry.

Widescreen refers to a larger width to height in the frame, compared to earlier historic aspect ratios. A feature-length film, or feature film, is of a conventional full length, usually 60 minutes or more, and can commercially stand by itself without other films in a ticketed screening. A short is a film that is not as long as a feature-length film, often screened with other shorts, or preceding a feature-length film. An independent is a film made outside the conventional film industry.

In U.S. usage, one talks of a screening or projection of a movie or video on a screen at a public or private theatre. In British English, a film showing happens at a cinema, never a theatre, which is a different medium and place altogether. A cinema usually refers to an arena designed specifically to exhibit films, where the screen is affixed to a wall, while a theatre usually refers to a place where live, non-recorded action or combination thereof occurs from a podium or other type of stage, including the amphitheatre. Theatres can still screen movies in them, though the theatre would be retrofitted to do so. One might propose going to the cinema when referring to the activity, or sometimes to the pictures in British English, whereas the U.S. expression is usually going to the movies. A cinema usually shows a mass-marketed movie using a front-projection screen process with either a film projector or, more recently, with a digital projector. But, cinemas may also show theatrical movies from their home video transfers that include Blu-ray Disc, DVD, and videocassette when they possess sufficient projection quality or based upon need, such as movies that exist only in their transferred state, which may be due to the loss or deterioration of the film master and prints from which the movie originally existed. Due to the advent of digital film production and distribution, physical film might be absent entirely. A double feature is a screening of two independently marketed, stand-alone feature films. A viewing is a watching of a film. Sales and at the box office refer to tickets sold at a theatre, or more currently, rights sold for individual showings. A release is the distribution and often simultaneous screening of a film. A preview is a screening in advance of the main release.

Any film may also have a sequel, which portrays events following those in the film. Bride of Frankenstein is an early example. When there are more films than one with the same characters, story arcs, or subject themes, these movies become a series, such as the James Bond series. And, existing outside a specific story timeline usually, does not exclude a film from being part of a series. A film that portrays events occurring earlier in a timeline with those in another film, but is released after that film, is sometimes called a prequel, an example being Butch and Sundance: The Early Days.

The credits, or end credits, are a list that gives credit to the people involved in the production of a film. Films from before the 1970’s usually start a film with credits, often ending with only a title card, saying The End or some equivalent, often an equivalent that depends on the language of the production. From then onward, a film’s credits usually appear at the end of most films. However, films with credits that end a film often repeat some credits at or near the start of a film and therefore appear twice, such as that film’s acting leads, while less frequently some appearing near or at the beginning only appear there, not at the end, which often happens to the director’s credit. The credits appearing at or near the beginning of a film are usually called titles or beginning titles. A post-credits scene is a scene shown after the end of the credits. Ferris Bueller’s Day Off has a post-credit scene in which Ferris tells the audience that the film is over and they should go home.

A film’s cast refers to a collection of the actors and actresses who appear, or star, in a film. A star is an actor or actress, often a popular one, and in many cases, a celebrity who plays a central character in a film. Occasionally the word can also be used to refer to the fame of other members of the crew, such as a director or other personality, such as Martin Scorsese. A crew is usually interpreted as the people involved in a film’s physical construction outside cast participation, and it could include directors, film editors, photographers, grips, gaffers, set decorators, prop masters, and costume designers. A person can both be part of a film’s cast and crew, such as Woody Allen, who directed and starred in Take the Money and Run.

A film goer, movie goer, or film buff is a person who likes or often attends films and movies, and any of these, though more often the latter, could also see oneself as a student of films and movies. Intense interest in films, film theory, and film criticism, is known as cinephilia. A film enthusiast is known as a cinephile or cineaste.

Preview

Read more about Test screening here.

A preview performance refers to a showing of a film to a select audience, usually for the purposes of corporate promotions, before the public film premiere itself. Previews are sometimes used to judge audience reaction, which if unexpectedly negative, may result in recutting or even refilming certain sections based on the audience response. One example of a film that was changed after a negative response from the test screening is 1982’s First Blood. After the test audience responded very negatively to the death of protagonist John Rambo (a Vietnam veteran) at the end of the film, the company wrote and re-shot a new ending in which the character survives.

Read more about the Film trailer here.

Trailers or previews are advertisements for films that will be shown in 1 to 3 months at a cinema. Back in the early days of cinema, with cinemas that had only one or two screens, only certain trailers were shown for the films that were going to be shown there. Later, when cinemas added more screens or new cinemas were built with a lot of screens, all different trailers were shown even if they were not going to play that film in that cinema. Film studios realised that the more trailers that were shown (even if it was not going to be shown in that particular cinema) the more patrons would go to a different cinema to see the film when it came out. The term trailer comes from their having originally been shown at the end of a film. That practice did not last long because patrons tended to leave the theatre after the films ended, but the name stuck. Trailers are now shown before the film, or when the first film in a double feature begins. Film trailers are also common on DVD’s and Blu-ray Discs, as well as on the Internet and mobile devices. Trailers are created to be engaging and interesting for viewers. As a result, in the Internet era, viewers often seek out trailers to watch them. Of the ten billion videos watched online annually in 2008, film trailers ranked third, after news and user-created videos. Teasers are a much shorter preview or advertisement that lasts only 10 to 30 seconds. Teasers are used to get patrons excited about a film coming out in the next six to twelve months. Teasers may be produced even before the film production is completed.

The Role Of Film In Culture

Films are cultural artefacts created by specific cultures, facilitating intercultural dialogue. It is considered to be an important art form that provides entertainment and historical value, often visually documenting a period of time. The visual basis of the medium gives it a universal power of communication, often stretched further through the use of dubbing or subtitles to translate the dialogue into other languages. Just seeing a location in a film is linked to higher tourism to that location, demonstrating how powerful the suggestive nature of the medium can be.

Education And Propaganda

Read more about Educational films here and Propaganda films here.

Film is used for a range of goals, including education and propaganda due to its ability to effectively intercultural dialogue. When the purpose is primarily educational, a film is called an educational film. Examples are recordings of academic lectures and experiments, or a film based on a classic novel. Film may be propaganda, in whole or in part, such as the films made by Leni Riefenstahl in Nazi Germany, U.S. war film trailers during World War II, or artistic films made under Stalin by Sergei Eisenstein. They may also be works of political protest, as in the films of Andrzej Wajda, or more subtly, the films of Andrei Tarkovsky. The same film may be considered educational by some, and propaganda by others as the Film is used for a range of goals, including education and propaganda due to its ability to effectively intercultural dialogue. When the purpose is primarily educational, a film is called an educational film. Examples are recordings of academic lectures and experiments, or a film based on a classic novel. Film may be propaganda, in whole or in part, such as the films made by Leni Riefenstahl in Nazi Germany, U.S. war film trailers during World War II, or artistic films made under Stalin by Sergei Eisenstein. They may also be works of political protest, as in the films of Andrzej Wajda, or more subtly, the films of Andrei Tarkovsky. The same film may be considered educational by some, and propaganda by others as the categorisation of a film can be subjective.

Production

Read more about Filmmaking here.

At its core, the means to produce a film depend on the content the filmmaker wishes to show, and the apparatus for displaying it e.g. the zoetrope merely requires a series of images on a strip of paper. Film production can, therefore, take as little as one person with a camera, or even without a camera, as in Stan Brakhage’s 1963 film Mothlight, or thousands of actors, extras, and crew members for a live-action, feature-length epic. The necessary steps for almost any film can be boiled down to conception, planning, execution, revision, and distribution. The more involved the production, the more significant each of the steps becomes. In a typical production cycle of a Hollywood-style film, these main stages are defined as development, pre-production, production, post-production and distribution.

This production cycle usually takes three years. The first year is taken up with development. The second year comprises preproduction and production. The third year, post-production and distribution. The bigger the production, the more resources it takes, and the more important financing becomes. Most feature films are artistic works from the creators’ perspective, e.g., film directors, cinematographers, screenwriters and for-profit business entities for the production companies.

Crew

Read more about the Film crew here.

A film crew is a group of people hired by a film company, and employed during the production or photography phase, for the purpose of producing a film or motion picture. Crew is distinguished from cast, who are the actors who appear in front of the camera or provide voices for characters in the film. The crew interacts with but is also distinct from the production staff, consisting of producers, managers, company representatives, their assistants, and those whose primary responsibility falls in the pre-production or post-production phases, such as screenwriters and film editors. Communication between production and crew generally passes through the director and his/her staff of assistants. Medium-to-large crews are generally divided into departments with well-defined hierarchies and standards for interaction and cooperation between the departments. Other than acting, the crew handles everything in the photography phase such as props and costumes, shooting, sound, electrics, i.e., lights, sets, and production special effects. Caterers (known in the film industry as craft services) are usually not considered part of the crew.

Technology

Read more about Cinema Techniques here.

Film stock consists of transparent celluloid, acetate, or polyester base coated with an emulsion containing light-sensitive chemicals. Cellulose nitrate was the first type of film base used to record motion pictures, but due to its flammability was eventually replaced by safer materials. Stock widths and the film format for images on the reel have had a rich history, though most large commercial films are still shot on (and distributed to theatres) as 35 mm prints. Originally moving picture film was shot and projected at various speeds using hand-cranked cameras and projectors; though 1000 frames per minute (162/3 frame/s) is generally cited as a standard silent speed, research indicates most films were shot between 16 frame/s and 23 frame/s and projected from 18 frame/s on up (often reels included instructions on how fast each scene should be shown). When synchronised sound film was introduced in the late 1920’s, a constant speed was required for the sound head. 24 frames per second was chosen because it was the slowest (and thus cheapest) speed which allowed for sufficient sound quality. The standard was set with Warner Bros.’s The Jazz Singer and their Vitaphone system in 1927. Improvements since the late 19th century include the mechanisation of cameras which allows them to record at a consistent speed and quiet camera design thus allowing sound recorded on-set to be usable without requiring large blimps to encase the camera, the invention of more sophisticated filmstocks and lenses, allowing directors to film in increasingly dim conditions, and the development of synchronized sound, allowing sound to be recorded at exactly the same speed as its corresponding action. The soundtrack can be recorded separately from shooting the film, but many parts of the soundtrack are usually recorded simultaneously for live-action pictures.

As a medium, film is not limited to motion pictures, since the technology developed as the basis for photography. It can be used to present a progressive sequence of still images in the form of a slideshow. Film has also been incorporated into multimedia presentations and often has importance as primary historical documentation. However, historic films have problems in terms of preservation and storage, and the motion picture industry is exploring many alternatives. Most films on cellulose nitrate base have been copied onto modern safety films. Some studios save colour films through the use of separation masters which are three B&W negatives each exposed through red, green, or blue filters (essentially a reverse of the Technicolor process). Digital methods have also been used to restore films, although their continued obsolescence cycle makes them (as of 2006) a poor choice for long-term preservation. Film preservation of decaying film stock is a matter of concern to both film historians and archivists and to companies interested in preserving their existing products in order to make them available to future generations (and thereby increase revenue). Preservation is generally a higher concern for nitrate and single-strip color films, due to their high decay rates; black-and-white films on safety bases and color films preserved on Technicolor imbibition prints tend to keep up much better, assuming proper handling and storage.

Some films in recent decades have been recorded using analogue video technology similar to that used in television production. Modern digital video cameras and digital projectors are gaining ground as well. These approaches are preferred by some film-makers, especially because footage shot with digital cinema can be evaluated and edited with non-linear editing systems (N.L.E.) without waiting for the film stock to be processed. The migration was gradual, and as of 2005, most major motion pictures were still shot on film.

Independent

Read more about Independent film here.

Independent filmmaking often takes place outside Hollywood or other major studio systems. An independent film (or indie film) is a film initially produced without financing or distribution from a major film studio. Creative, business and technological reasons have all contributed to the growth of the indie film scene in the late 20th and early 21st century. On the business side, the costs of big-budget studio films also lead to conservative choices in cast and crew. There is a trend in Hollywood towards co-financing (over two-thirds of the films put out by Warner Bros. in 2000 were joint ventures, up from 10% in 1987). A hopeful director is almost never given the opportunity to get a job on a big-budget studio film unless he or she has significant industry experience in film or television. Also, the studios rarely produce films with unknown actors, particularly in lead roles.

Before the advent of digital alternatives, the cost of professional film equipment and stock was also a hurdle to being able to produce, direct, or star in a traditional studio film. The advent of consumer camcorders in 1985, and more importantly, the arrival of high-resolution digital video in the early 1990’s, have lowered the technology barrier to film production significantly. Both production and post-production costs have been significantly lowered. In the 2000’s, the hardware and software for post-production could be installed in a commodity-based personal computer. Technologies such as DVD’s, FireWire connections and a wide variety of professional and consumer-grade video editing software make film-making relatively affordable.

Since the introduction of digital video D.V. technology, the means of production have become more democratised. Filmmakers can conceivably shoot a film with a digital video camera and edit the film, create and edit the sound and music, and mix the final cut on a high-end home computer. However, while the means of production may be democratised, financing, distribution, and marketing remain difficult to accomplish outside the traditional system. Most independent filmmakers rely on film festivals to get their films noticed and sold for distribution. The arrival of internet-based video websites such as YouTube and Veoh has further changed the filmmaking landscape, enabling indie filmmakers to make their films available to the public.

The Lumiere Brothers were among the first filmmakers.

Open Content Film

Read more about Open content film here.

An open-content film is much like an independent film, but it is produced through open collaborations. Its source material is available under a license which is permissive enough to allow other parties to create fan fiction or derivative works, than a traditional copyright. Like independent filmmaking, open source filmmaking takes place outside Hollywood or other major studio systems. For example, the film Balloon was based on a real event during the Cold War.

Fan Film

Read more about Fan films here.

A fan film is a film or video inspired by a film, television program, comic book or a similar source, created by fans rather than by the source’s copyright holders or creators. Fan filmmakers have traditionally been amateurs, but some of the most notable films have actually been produced by professional filmmakers as film school class projects or as demonstration reels. Fan films vary tremendously in length, from short faux-teaser trailers for non-existent motion pictures to rarer full-length motion pictures.

Distribution

Read more about Film distribution here and Film release here.

Film distribution is the process through which a film is made available for viewing by an audience. This is normally the task of a professional film distributor, who would determine the marketing strategy of the film, the media by which a film is to be exhibited or made available for viewing, and may set the release date and other matters. The film may be exhibited directly to the public either through a cinema (historically the main way films were distributed) or television for personal home viewing including on DVD-Video or Blu-ray Disc, video-on-demand, online downloading, television programs through broadcast syndication etc. Other ways of distributing a film include rental or personal purchase of the film in a variety of media and formats, such as VHS tape or DVD, or Internet downloading or streaming using a computer.

Animation

Read more about Animation here.

Animation is a technique in which each frame of a film is produced individually, whether generated as a computer graphic (by photographing a drawn image), or by repeatedly making small changes to a model unit (see claymation and stop motion), and then photographing the result with a special animation camera. When the frames are strung together and the resulting film is viewed at a speed of 16 or more frames per second, there is an illusion of continuous movement (due to the phi phenomenon). Generating such a film is very labour-intensive and tedious, though the development of computer animation has greatly sped up the process. Because animation is very time-consuming and often very expensive to produce, the majority of animation for television and films comes from professional animation studios. However, the field of independent animation has existed at least since the 1950’s, with animation being produced by independent studios and sometimes by a single person. Several independent animation producers have gone on to enter the professional animation industry.

Limited animation is a way of increasing production and decreasing the costs of animation by using shortcuts in the animation process. This method was pioneered by U.P.A. and popularized by Hanna-Barbera in the United States, and by Osamu Tezuka in Japan, and adapted by other studios as cartoons moved from movie theatres to television. Although most animation studios are now using digital technologies in their productions, there is a specific style of animation that depends on film. Camera-less animation, made famous by filmmakers like Norman McLaren, Len Lye, and Stan Brakhage, is painted and drawn directly onto pieces of film, and then run through a projector.

Further Information

Click on the links below to read more about the subject matter.

Bibliography of film by genre.

Docufiction (hybrid genre).

Glossary of motion picture terms.

Index of video-related articles.

List of books on films.

List of film awards.

List of film festivals.

Lists of films.

List of film periodicals.

List of years in film.

Lost film.

Outline of film.

Television film.

The Movies, a simulation game about the film industry, taking place at the dawn of cinema.

Web film.

Read more about Film here.

Blog Posts

Films: Angel Studios.

Films: Sound Of Freedom.

Films: Tim Ballard.

Notes And Links

Article source: Wikipedia and is subject to change.

Bence Szemerey on Pexels – The image shown at the top of this page is the copyright of Bence Szemerey. You can find more great work from the photographer Bence and lots more free stock photos at Pexels.

The Prof. Stampfer’s Stroboscopische Scheibe No. X animation above is the copyright of Simon Ritter von Stampfer and is in the public domain.

The Horse In Motion animation above is the copyright of Eadweard Muybridge and is in the public domain.

The image above of a picture of Ottomar’s Anschutz’s electrotachyscope is copyright unknown as is in the public domain.

The video above of Roundhay Garden Scene is in the public domain. You can read more about the film by clicking here.

The video above of Pauvre Pierrot is in the public domain. You can read more about the film by clicking here.

The video above of Le voyage dans la lune is in the public domain. You can read more about the film by clicking here.

The video above of The Bond is in the public domain. You can read more about the film by clicking here.

The image above of a picture of Salah Zulfikar, is copyright unknown as is in the public domain.

The image above of The Bolex H16 Reflex camera is the copyright of Wikipedia user Janke and is in the public domain.

The image above of The Most Productive Cinemas Around The World is copyright unknown via Wikipedia. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of The Lumiere Brothers is copyright unknown as is in the public domain.

The image above of an Animated Horse is the copyright of Wikipedia user Janke and is in the public domain. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.5).

Creative Commons – Official website. They offer better sharing, advancing universal access to knowledge and culture, and fostering creativity, innovation, and collaboration.

IMDb – Official website. IMDb is an online database of information related to films, television series, podcasts, home videos, video games, and streaming content online, including cast, production crew and personal biographies, plot summaries, trivia, ratings, and fan and critical reviews.

IMDb on YouTube.

Wikipedia – Official website. Wikipedia is a free online encyclopedia that anyone can edit in good faith. Its purpose is to benefit readers by containing information on all branches of knowledge. Hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation, it consists of freely editable content, whose articles also have numerous links to guide readers to more information.