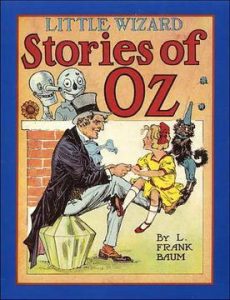

The Little Wizard Stories of Oz is related to the Oz series of books.

Click here to download this book.

Read this book online and get more download options and a bibliographic record on Project Gutenberg by clicking here.

You can download the main fourteen fantasy books in the Oz series by L. Frank Baum via Project Gutenberg by clicking here.

About Little Wizard Stories Of Oz

Little Wizard Stories of Oz is a set of six short stories written for young children by L. Frank Baum. The six tales were published in separate small booklets, Oz books in miniature, in 1913, and then in a collected edition in 1914 with illustrations by John R. Neill. Each booklet is 29 pages long, and printed in blue ink rather than black.

Development

The stories were part of a project, by Baum and his publisher Reilly & Britton, to revitalize and continue the series of Oz books that Baum had written up to that date. The story collection effectively constitutes a fifteenth Oz book by Baum.

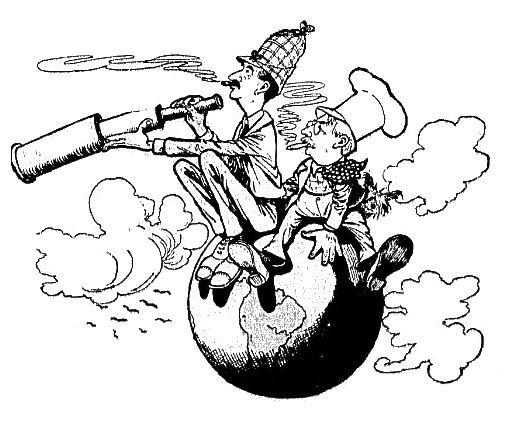

Baum had attempted to end the Oz series with the sixth book, The Emerald City of Oz (1910). In the final chapter of that book, he sealed off the Land of Oz from the outside world. He began a new series of books with The Sea Fairies (1911) and Sky Island (1912). Also, he reacted to his 1911 bankruptcy by increasing his literary output. He produced five books that year, his greatest output since 1907. Baum tried to launch two other juvenile novel series in 1911, with The Daring Twins, released under his own name, and The Flying Girl, under his Edith Van Dyne pseudonym.

None of the new series was as successful as the previous Baum and Van Dyne series, the Oz books and Aunt Jane’s Nieces. Both the Flying Girl and Daring Twins series ended with their second volumes, The Flying Girl and Her Chum and Phoebe Daring, both published in 1912. Disappointing sales through 1911 and 1912 convinced Baum and Reilly & Britton that a return to Oz was needed. Baum wrote The Patchwork Girl of Oz for a 1913 release, and in the same year, his publisher issued the six Little Wizard stories in individual booklets at a cost of $0.15 each. The goal was to reach the youngest beginning readers and create in them an interest in the larger Oz canon, as part of a promotion of L. Frank Baum and all of his books.

Content And Publication

The six tales in the Little Wizard Stories are:

The Cowardly Lion and the Hungry Tiger.

Little Dorothy and Toto.

Tiktok and the Nome King.

Ozma and the Little Wizard.

Jack Pumpkinhead and the Sawhorse.

The Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman.

The strategy of reaching beginning readers was successful enough for Reilly & Britton to repeat it within a few years. The publisher released selections from L. Frank Baum’s Juvenile Speaker (1910) in six smaller books called The Snuggle Tales in 1916 – 1917, and again as The Oz-Man Tales in 1920.

Four of the Little Wizard Stories were re-issued in 1932 in a new form, as The Little Oz Books with Jig Saw Oz Puzzles. A year or two later the four tales were released again, as part of a promotion for a Wizard of Oz radio program. Rand McNally published the six stories in three booklets in 1939.

Read more about Little Wizard Stories here.

Blog Posts

Books: The Oz Series By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Marvelous Land Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Ozma Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Dorothy And The Wizard In Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Road To Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Emerald City Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Patchwork Girl Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Tik-Tok Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Scarecrow Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Rinkitink In Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Lost Princess Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Tin Woodman Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Magic Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Glinda Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

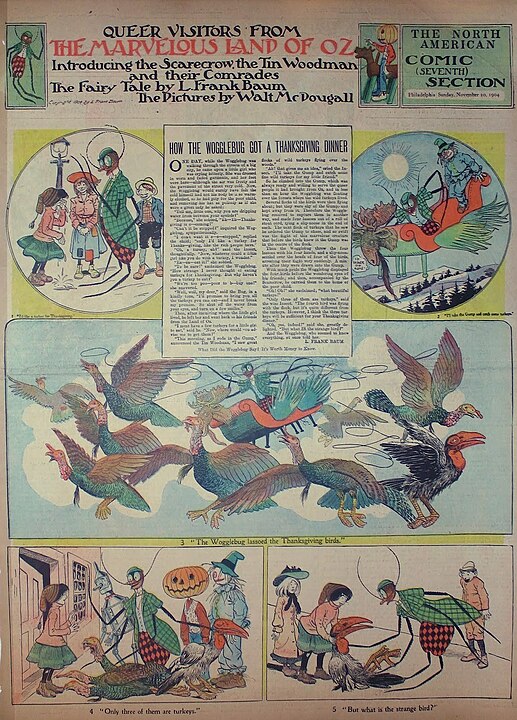

Books: Queer Visitors From The Marvelous Land Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Notes And Links

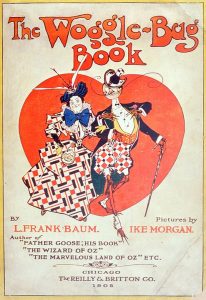

The 1905 first edition front cover image shown at the top of this page is copyright of John R. Neill and is in the Public Domain via Wikipedia. It has a fair use licence.

Project Gutenberg – Project Gutenberg is an online library of free e-books and was the first provider of free electronic books. Michael Hart, the founder of Project Gutenberg, invented e-books in 1971 and his memory continues to inspire the creation of them and related content today.

The Wonderful Wiki of Oz – Official website. A wonderful and welcoming encyclopedia of all things Oz that anyone can edit or contribute Oz-related information and Oz facts to enjoy.

The Oz Archive on Facebook – Archiving and celebrating the legacy of Oz.

The Oz Archive on Twitter – Archiving and celebrating the legacy of Oz.

The Oz Archive on Instagram – Archiving and celebrating the legacy of Oz.

The Oz Archive on TikTok – Archiving and celebrating the legacy of Oz.