I have many happy memories over the decades, especially family ones from when I was younger in the 70’s and ’80s and when my kids were younger. Sadly my mental health suffered in my adult years, especially in the 2010’s right up to the start of the 2020’s and it was difficult to enjoy them and love them like I used to but thankfully I can start to LOVE CHRISTMAS again.

For me, Christmas is about being with family and friends. It is enjoying good company and eating, drinking and being merry. It is reminiscing about the happy Christmases of old and remembering people and animals that shared those precious times with us but are no longer here with us. It is about wonderful Christmas trees and the giving and recieving of presents. It is about the beautiful colours that come with it. It is about traditions. It is about listening to Christmas music and watching Christmas films and programmes. It is about the spirit of Christmas and the feeling of peace. It is not just a holiday, it is a state of mind.

Living in the mostly Christian country of England when I was younger (not so much now) and being a former Christian myself I always celebrated Christmas regarding the birth of Jesus Christ.

The older I got, as an atheist, I came to realise the bible just contradicts itself and is full of fictional stories. The date of that birth itself, December the 25th, can’t be agreed upon or proved throughout the centuries (and I’m not bothering to cover all that below) but to be honest I don’t care about the date or what did or didn’t happen on it or if anyone involved with it is real but that is not here or there.

I am someone who tries hard to avoid talking about religion, royalty and politics but it would be impossible to talk about Christmas and not refer to religion regarding what is written below, however, it is written respectfully. As I have always said about religion, as long as it doesn’t involve harm or hatred and is peaceful, I will respect your right to believe whatever you like as long as you respect my right not to believe. Royalty and politics are briefly mentioned as it is hard to avoid them when it is part of Christmas history but mainly I wanted to keep this page interesting and informative about Christmas.

If you are reading this in December then have a very HAPPY CHRISTMAS!

A Nativity Scene made with Christmas lights.

About Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, primarily observed on December the 25th as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year, it follows the season of Advent (which begins four Sundays before) or the Nativity Fast, and initiates the season of Christmastide, which historically in the West lasts twelve days and culminates on Twelfth Night. Christmas Day is a public holiday in many countries, is celebrated religiously by a majority of Christians, as well as culturally by many non-Christians, and forms an integral part of the holiday season organised around it.

The traditional Christmas narrative recounted in the New Testament, known as the Nativity of Jesus, says that Jesus was born in Bethlehem, under messianic prophecies. When Joseph and Mary arrived in the city, the inn had no room so they were offered a stable where the Christ Child was soon born, with angels proclaiming this news to shepherds who then spread the word.

There are different hypotheses regarding the date of Jesus’ birth and in the early fourth century, the church fixed the date as December the 25th. This corresponds to the traditional date of the winter solstice on the Roman calendar. It is exactly nine months after the Annunciation on March the 25th, also the date of the spring equinox. Most Christians celebrate on December the 25th in the Gregorian calendar, which has been adopted almost universally in the civil calendars used in countries worldwide. However, some of the Eastern Christian Churches celebrate Christmas on December the 25th of the older Julian calendar, which currently corresponds to January the 7th in the Gregorian calendar. For Christians, believing that God came into the world in the form of man to atone for the sins of humanity, rather than knowing Jesus’ exact birth date, is considered to be the primary purpose of celebrating Christmas.

The celebratory customs associated in various countries with Christmas have a mix of pre-Christian, Christian, and secular themes and origins. Popular modern customs of the holiday include gift giving, completing an Advent calendar or Advent wreath, Christmas music and caroling, watching Christmas movies, viewing a Nativity play, an exchange of Christmas cards, church services, a special meal, and the display of various Christmas decorations, including Christmas trees, Christmas lights, nativity scenes, garlands, wreaths, mistletoe, and holly. In addition, several closely related and often interchangeable figures, known as Father Christmas, Santa Claus, Saint Nicholas, and the Christkind, are associated with bringing gifts to children during Christmas and have their own body of traditions and lore. Because gift-giving and many other aspects of the Christmas festival involve heightened economic activity, the holiday has become a significant event and a key sales period for retailers and businesses. Over the past few centuries, Christmas has had a steadily growing economic effect in many regions of the world.

Etymology

Other Names

In addition to Christmas, the holiday has had various other English names throughout its history. The Anglo-Saxons referred to the feast as midwinter, or, more rarely, as Nātiuiteð, which comes from the Latin nātīvitās. Nativity, meaning birth, is also from the Latin nātīvitās. In Old English, Gēola (Yule) referred to the period corresponding to December and January, which was eventually equated with Christian Christmas. Noel (also Nowel or Nowell, as in The First Nowell) entered English in the late 14th century and is from the Old French noël or naël, itself ultimately from the Latin nātālis (diēs) meaning birth (day).

Koleda is the traditional Slavic name for Christmas and the period from Christmas to Epiphany or, more generally, to Slavic Christmas-related rituals, some dating to pre-Christian times.

The History Of Christmas

In the 2nd century, the earliest church records indicate that Christians were remembering and celebrating the birth of Jesus, an observance that sprang up organically from the authentic devotion of ordinary believers although a set date was not agreed on. Though Christmas did not appear on the lists of festivals given by the early Christian writers Irenaeus and Tertullian, the early Church Fathers John Chrysostom, Augustine of Hippo, and Jerome attested to December the 25th as the date of Christmas toward the end of the fourth century. A passage in Commentary on the Prophet Daniel (AD 204) by Hippolytus of Rome identifies December the 25th as Jesus’s birth date, but this passage is considered a later interpolation.

In the East, the birth of Jesus was celebrated in connection with the Epiphany on January the 6th. This holiday was not primarily about Christ’s birth, but rather his baptism. Christmas was promoted in the East as part of the revival of Orthodox Christianity that followed the death of the pro-Arian Emperor Valens at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. The feast was introduced in Constantinople in 379, in Antioch by John Chrysostom towards the end of the fourth century, probably in 388, and in Alexandria in the following century. The Georgian Iadgari demonstrates that Christmas was celebrated in Jerusalem by the sixth century.

Post-Classical History

Christmas played a role in the Arian controversy of the fourth century. After this controversy ran its course, the prominence of the holiday declined for a few centuries.

In the Early Middle Ages, Christmas Day was overshadowed by Epiphany, which in Western Christianity focused on the visit of the magi. However, the medieval calendar was dominated by Christmas-related holidays. The forty days before Christmas became the forty days of St. Martin (which began on November the 11th, the feast of St. Martin of Tours), now known as Advent. In Italy, former Saturnalian traditions were attached to Advent. Around the 12th century, these traditions transferred again to the Twelve Days of Christmas (December the 25th to January the 5th). This is a time that appears in the liturgical calendars as Christmastide or Twelve Holy Days.

In 567, the Council of Tours put in place the season of Christmastide, proclaiming the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast. This was done to solve the administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east.

The prominence of Christmas Day increased gradually after Charlemagne was crowned Emperor on Christmas Day in 800. King Edmund the Martyr was anointed on Christmas in 855 and King William I of England was crowned on Christmas Day 1066.

By the High Middle Ages, the holiday had become so prominent that chroniclers routinely noted where various magnates celebrated Christmas. King Richard II of England hosted a Christmas feast in 1377 at which 28 oxen and 300 sheep were eaten. The Yule boar was a common feature of medieval Christmas feasts. Carolling also became popular and was originally performed by a group of dancers who sang. The group was composed of a lead singer and a ring of dancers that provided the chorus. Various writers of the time condemned carolling as lewd, indicating that the unruly traditions of Saturnalia and Yule may have continued in this form. Misrule (drunkenness, promiscuity, gambling) was also an important aspect of the festival. In England, gifts were exchanged on New Year’s Day, and there was a special Christmas ale.

Christmas during the Middle Ages was a public festival that incorporated ivy, holly, and other evergreens. Christmas gift-giving during the Middle Ages was usually between people with legal relationships, such as tenants and landlords. The annual indulgence in eating, dancing, singing, sporting, and card playing escalated in England, and by the 17th century, the Christmas season featured lavish dinners, elaborate masques, and pageants. In 1607, King James I insisted that a play be acted on Christmas night and that the court indulge in games. It was during the Reformation in 16th – 17th-century Europe that many Protestants changed the gift bringer to the Christ Child or Christkindl, and the date of giving gifts changed from December the 6th to Christmas Eve.

The Nativity by unknown.

This beautiful image comes from a 14th-century Missal. It is made from parchment and originates from East Anglia. It is considered a very important manuscript as it is one of the earliest examples of a Missal of an English source.

Sarum Missals were books produced by the Church during the Middle Ages for celebrating Mass throughout the year

The Coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas of 800 by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld.

Modern History

17th And 18th Centuries

Following the Protestant Reformation, many of the new denominations, including the Anglican Church and Lutheran Church, continued to celebrate Christmas. In 1629, the Anglican poet John Milton penned On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity, a poem that has since been read by many during Christmastide. Donald Heinz, a professor at California State University, states that Martin Luther inaugurated a period in which Germany would produce a unique culture of Christmas, much copied in North America. Among the congregations of the Dutch Reformed Church, Christmas was celebrated as one of the principal evangelical feasts.

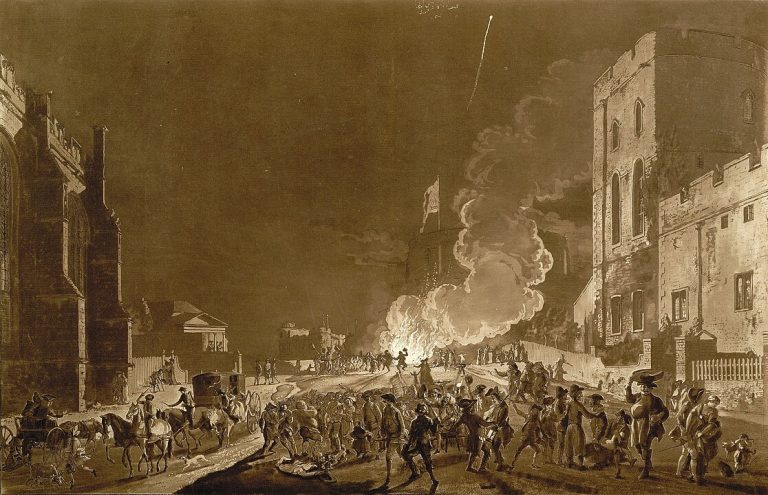

However, in 17th century England, some groups such as the Puritans strongly condemned the celebration of Christmas, considering it a Catholic invention and the trappings of popery or the rags of the Beast. In contrast, the established Anglican Church pressed for a more elaborate observance of feasts, penitential seasons, and saints’ days. The calendar reform became a major point of tension between the Anglican party and the Puritan party. The Catholic Church also responded, promoting the festival in a more religiously oriented form. King Charles I of England directed his noblemen and gentry to return to their landed estates in midwinter to keep up their old-style Christmas generosity. Following the Parliamentarian victory over Charles I during the English Civil War, England’s Puritan rulers banned Christmas in 1647.

Protests followed as pro-Christmas rioting broke out in several cities and for weeks Canterbury was controlled by the rioters, who decorated doorways with holly and shouted royalist slogans. Football, among the sports the Puritans banned on a Sunday, was also used as a rebellious force. When Puritans outlawed Christmas in England in December 1647 the crowd brought out footballs as a symbol of festive misrule. The book, The Vindication of Christmas (London, 1652), argued against the Puritans and makes note of Old English Christmas traditions, dinner, roast apples on the fire, card playing, dances with plow-boys and maidservants, old Father Christmas and carol singing. During the ban, semi-clandestine religious services marking Christ’s birth continued to be held, and people sang carols in secret.

It was restored as a legal holiday in England with the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 when Puritan legislation was declared null and void, with Christmas again freely celebrated in England. Many Calvinist clergymen disapproved of Christmas celebrations. As such, in Scotland, the Presbyterian Church of Scotland discouraged the observance of Christmas, and though James VI commanded its celebration in 1618, church attendance was scant. The Parliament of Scotland officially abolished the observance of Christmas in 1640, claiming that the church had been purged of all superstitious observation of days. Whereas in England, Wales and Ireland Christmas Day is a common law holiday, having been a customary holiday since time immemorial, it was not until 1871 that it was designated a bank holiday in Scotland. The diary of James Woodforde, from the latter half of the 18th century, details the observance of Christmas and celebrations associated with the season over several years.

As in England, Puritans in Colonial America staunchly opposed the observation of Christmas. The Pilgrims of New England pointedly spent their first 25th of December in the New World working normally. Puritans such as Cotton Mather condemned Christmas both because scripture did not mention its observance and because Christmas celebrations of the day often involved boisterous behaviour. Many non-Puritans in New England deplored the loss of the holidays enjoyed by the labouring classes in England. Christmas observance was outlawed in Boston in 1659. The ban on Christmas observance was revoked in 1681 by English governor Edmund Andros, but it was not until the mid-19th century that celebrating Christmas became fashionable in the Boston region.

At the same time, Christian residents of Virginia and New York observed the holiday freely. Pennsylvania Dutch settlers, predominantly Moravian settlers of Bethlehem, Nazareth, and Lititz in Pennsylvania and the Wachovia settlements in North Carolina, were enthusiastic celebrators of Christmas. The Moravians in Bethlehem had the first Christmas trees in America as well as the first Nativity Scenes. Christmas fell out of favour in the United States after the American Revolution, when it was considered an English custom. George Washington attacked Hessian (German) mercenaries on the day after Christmas during the Battle of Trenton on December the 26th, 1776. Christmas was much more popular in Germany than in America at this time.

With the atheistic Cult of Reason in power during the era of Revolutionary France, Christian Christmas religious services were banned and the Three Kings cake was renamed the equality cake under anticlerical government policies.

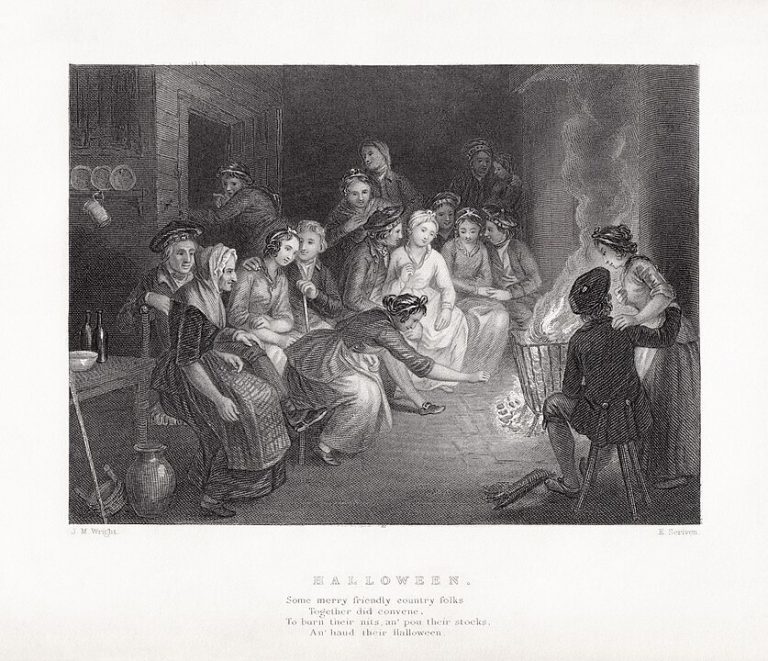

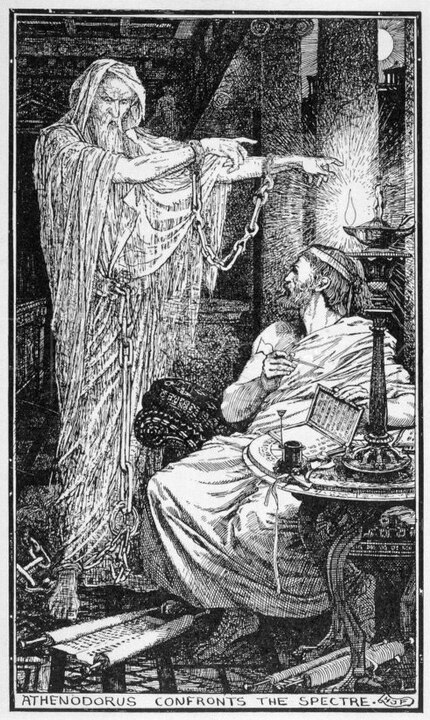

The Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas by Josiah King.

This was published after Christmas and reinstated as a holy day in England. It shows the frontispiece to King’s pamphlet The Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas, published in 1687. He had previously published a pamphlet with a very similar title The Examination and Tryall of Old Father Christmas in 1658 using the same image as the frontispiece.

19th Century

In the early 19th century, Christmas festivities and services became widespread with the rise of the Oxford Movement in the Church of England that emphasised the centrality of Christmas in Christianity and charity to the poor, along with Charles Dickens, Washington Irving, and other authors emphasising family, children, kind-heartedness, gift-giving, and Father Christmas (for Dickens) or Santa Claus (for Irving).

In the early-19th century, writers imagined Tudor-period Christmas as a time of heartfelt celebration. In 1843, Charles Dickens wrote the novel A Christmas Carol, which helped revive the spirit of Christmas and seasonal merriment. Its instant popularity played a major role in portraying Christmas as a holiday emphasising family, goodwill, and compassion.

Dickens sought to construct Christmas as a family-centred festival of generosity, linking worship and feasting, within a context of social reconciliation. Superimposing his humanitarian vision of the holiday, in what has been termed Carol Philosophy, Dickens influenced many aspects of Christmas that are celebrated today in Western culture, such as family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games, and a festive generosity of spirit. A prominent phrase from the tale, Merry Christmas, was popularised following the appearance of the story. This coincided with the appearance of the Oxford Movement and the growth of Anglo-Catholicism, which led to a revival in traditional rituals and religious observances.

In 1822, Clement Clarke Moore wrote the poem A Visit From St. Nicholas (popularly known by its first line Twas the Night Before Christmas). The poem helped popularise the tradition of exchanging gifts, and seasonal Christmas shopping began to assume economic importance. This also started the cultural conflict between the holiday’s spiritual significance and its associated commercialism which some see as corrupting the holiday. In her 1850 book The First Christmas in New England, Harriet Beecher Stowe includes a character who complains that the true meaning of Christmas was lost in a shopping spree.

While the celebration of Christmas was not yet customary in some regions in the U.S., Henry Wadsworth Longfellow detected a transition state about Christmas in New England in 1856. He stated that the old Puritan feeling prevented it from being a cheerful, hearty holiday, though every year made it more so. In Reading, Pennsylvania, a newspaper remarked in 1861, that “even our Presbyterian friends who have hitherto steadfastly ignored Christmas threw open their church doors and assembled in force to celebrate the anniversary of the Savior’s birth.”

The First Congregational Church of Rockford, Illinois, (although of genuine Puritan stock) was preparing for a grand Christmas jubilee, a news correspondent reported in 1864. By 1860, fourteen states including several from New England had adopted Christmas as a legal holiday. In 1875, Louis Prang introduced the Christmas card to Americans. He has been called the father of the American Christmas card. On June the 28th, 1870, Christmas was formally declared a United States federal holiday.

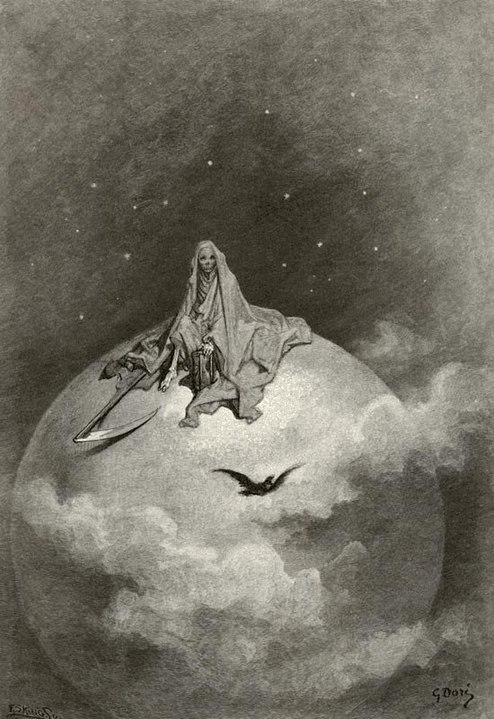

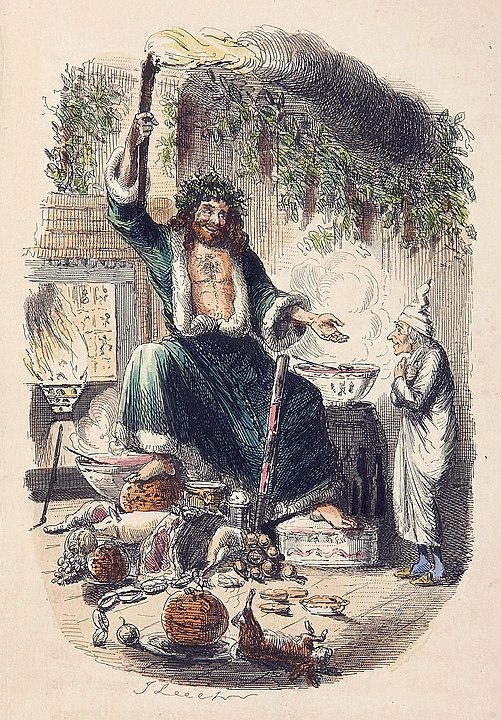

Scrooge’s Third Visitor by John Leech.

This image is from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol published in 1843. It is from one of four hand-coloured etchings included in the first edition. There were also four black and white engravings.

The Queen’s Christmas Tree at Windsor Castle by Joseph Lionel Williams.

This wood engraving print was made for The Illustrated London News, Christmas Number 1848.

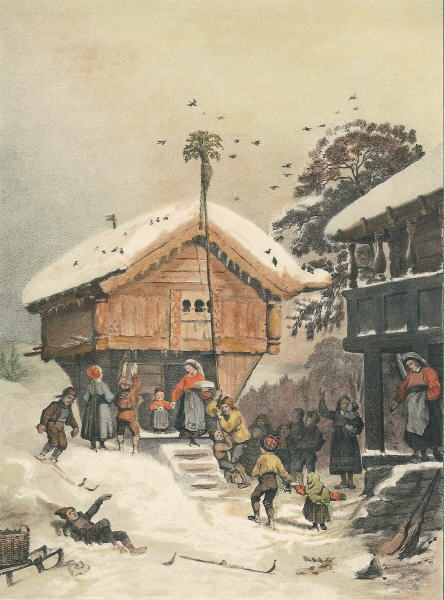

A Norwegian Christmas by Adolph Tidemand.

This painting is from 1846.

20th Century

During the First World War and particularly (but not exclusively) in 1914, a series of informal truces took place for Christmas between opposing armies. The truces, which were organised spontaneously by fighting men, ranged from promises not to shoot (shouted at a distance to ease the pressure of war for the day) to friendly socialising, gift-giving and even sport between enemies. These incidents became a well-known and semi-mythologised part of popular memory. They have been described as a symbol of common humanity even in the darkest of situations and used to demonstrate to children the ideals of Christmas.

Up to the 1950’s in the United Kingdom, many Christmas customs were restricted to the upper and middle classes. Most of the population had not yet adopted many Christmas rituals that later became popular, including Christmas trees. Christmas dinner would normally include beef or goose, not turkey as would later be common. Children would get fruit and sweets in their stockings rather than elaborate gifts. The full celebration of a family Christmas with all the trimmings only became widespread with increased prosperity from the 1950’s. National papers were published on Christmas Day until 1912. Post was still delivered on Christmas Day until 1961. League football matches continued in Scotland until the 1970’s while in England they ceased at the end of the 1950’s.

The Christmas Visit by unknown.

This postcard is from circa 1910.

Nativity

The gospels of Luke and Matthew describe Jesus as being born in Bethlehem to the Virgin Mary. In the Gospel of Luke, Joseph and Mary travel from Nazareth to Bethlehem to be counted for a census, and Jesus is born there and placed in a manger. Angels proclaim him a saviour for all people, and three shepherds come to adore him. In the Gospel of Matthew, by contrast, three magi follow a star to Bethlehem to bring gifts to Jesus, born the king of the Jews. King Herod orders the massacre of all the boys less than two years old in Bethlehem, but the family flees to Egypt and later returns to Nazareth.

Read more about The Nativity here.

Adoration of the Shepherds by Gerard van Honthorst.

This painting of Mary, Jesus and the shepherds was created in 1622.

Relation To Concurrent Celebrations

Many popular customs associated with Christmas developed independently of the commemoration of Jesus’ birth, with some claiming that certain elements are Christianised and have origins in pre-Christian festivals that were celebrated by pagan populations who were later converted to Christianity. Other scholars reject these claims and affirm that Christmas customs largely developed in a Christian context. The prevailing atmosphere of Christmas has also continually evolved since the holiday’s inception, ranging from a sometimes raucous, drunken, carnival-like state in the Middle Ages, to a tamer family-oriented and children-centered theme introduced in a 19th-century transformation. The celebration of Christmas was banned on more than one occasion within certain groups, such as the Puritans and Jehovah’s Witnesses (who do not celebrate birthdays in general), due to concerns that it was too unbiblical.

Prior to and through the early Christian centuries, winter festivals were the most popular of the year in many European pagan cultures. Reasons included the fact that less agricultural work needed to be done during the winter, as well as an expectation of better weather as spring approached. Celtic winter herbs such as mistletoe and ivy, and the custom of kissing under a mistletoe, are common in modern Christmas celebrations in the English-speaking countries.

The pre-Christian Germanic peoples (including the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse) celebrated a winter festival called Yule, held in the late December to early January period, yielding modern English yule, today used as a synonym for Christmas. In Germanic language-speaking areas, numerous elements of modern Christmas folk custom and iconography may have originated from Yule, including the Yule log, Yule boar, and the Yule goat. Often leading a ghostly procession through the sky (the Wild Hunt), the long-bearded god Odin is referred to as the Yule one and Yule father in Old Norse texts, while other gods are referred to as Yule beings. On the other hand, as there are no reliable existing references to a Christmas log prior to the 16th century, the burning of the Christmas block may have been an early modern invention by Christians unrelated to the pagan practice.

In eastern Europe also, pre-Christian traditions were incorporated into Christmas celebrations there, an example being the Koleda, which shares parallels with the Christmas carol.

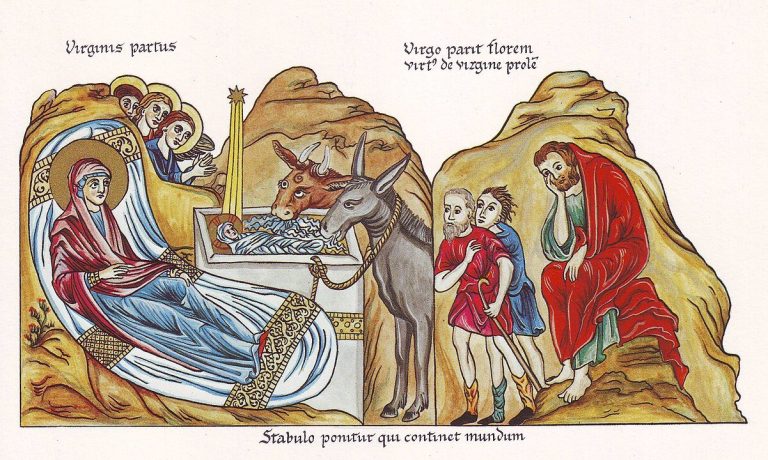

The Nativity of Christ by Herrad of Landsberg.

This 12th-century, medieval illustration is from the Hortus deliciarum.

Observance And Traditions

Christmas Day is celebrated as a major festival and public holiday in countries around the world, including many whose populations are mostly non-Christian. In some non-Christian areas, periods of former colonial rule introduced the celebration (e.g. Hong Kong); in others, Christian minorities or foreign cultural influences have led populations to observe the holiday. Countries such as Japan, where Christmas is popular despite there being only a small number of Christians, have adopted many of the cultural aspects of Christmas, such as gift-giving, decorations, and Christmas trees. A similar example is in Turkey, being Muslim-majority and with a small number of Christians, where Christmas trees and decorations tend to line public streets during the festival.

Among countries with a strong Christian tradition, a variety of Christmas celebrations have developed that incorporate regional and local cultures.

Christmas at the Annunciation Church in Nazareth.

This photo by Dan Hadani, from his collection Collection at the National Library of Israel, was taken on Christmas Eve, 1965.

Decorations

Nativity scenes are known from 10th-century Rome. They were popularised by Saint Francis of Assisi from 1223, quickly spreading across Europe. Different types of decorations developed across the Christian world, dependent on local tradition and available resources, and can vary from simple representations of the crib to far more elaborate sets. Renowned manger scene traditions include the colourful Krakow szopka in Poland, which imitate Krakow’s historical buildings as settings, the elaborate Italian presepi (Neapolitan, Genoese and Bolognese), or the Provencal creches in southern France, using hand-painted terracotta figurines called santons. In certain parts of the world, notably Sicily, living nativity scenes following the tradition of Saint Francis are a popular alternative to static creches. The first commercially produced decorations appeared in Germany in the 1860’s, inspired by paper chains made by children. In countries where a representation of the Nativity scene is very popular, people are encouraged to compete and create the most original or realistic ones. Within some families, the pieces used to make the representation are considered a valuable family heirloom.

The traditional colours of Christmas decorations are red, green, and gold. Red symbolises the blood of Jesus, which was shed in his crucifixion, green symbolises eternal life, and in particular the evergreen tree, which does not lose its leaves in the winter and gold is the first colour associated with Christmas, as one of the three gifts of the Magi, symbolising royalty.

The Christmas tree was first used by German Lutherans in the 16th century, with records indicating that a Christmas tree was placed in the Cathedral of Strassburg in 1539, under the leadership of the Protestant Reformer, Martin Bucer. In the United States, these German Lutherans brought the decorated Christmas tree with them. The Moravians put lighted candles on the trees. When decorating the Christmas tree, many individuals place a star at the top of the tree symbolising the Star of Bethlehem, a fact recorded by The School Journal in 1897. Professor David Albert Jones of Oxford University wrote that in the 19th century, it became popular for people to also use an angel to top the Christmas tree in order to symbolise the angels mentioned in the accounts of the Nativity of Jesus. Aditionally, in the context of a Christian celebration of Christmas, the Christmas tree, being evergreen in colour, is symbolic of Christ, who offers eternal life and the candles or lights on the tree represent the Light of the World. Christian services for family use and public worship have been published for the blessing of a Christmas tree, after it has been erected. The Christmas tree is considered by some as Christianisation of pagan tradition and ritual surrounding the Winter Solstice, which included the use of evergreen boughs, and an adaptation of pagan tree worship. According to eighth-century biographer Æddi Stephanus, Saint Boniface (634 – 709), who was a missionary in Germany, took an ax to an oak tree dedicated to Thor and pointed out a fir tree, which he stated was a more fitting object of reverence because it pointed to heaven and it had a triangular shape, which he said was symbolic of the Trinity. The English language phrase Christmas tree is first recorded in 1835 and represents an importation from the German language.

Since the 16th century, the poinsettia, a native plant from Mexico, has been associated with Christmas carrying the Christian symbolism of the Star of Bethlehem; in that country it is known in Spanish as the Flower of the Holy Night. Other popular holiday plants include holly, mistletoe, red amaryllis, and Christmas cactus.

Other traditional decorations include bells, candles, candy canes, stockings, wreaths, and angels. Both the displaying of wreaths and candles in each window are a more traditional Christmas display. The concentric assortment of leaves, usually from an evergreen, make up Christmas wreaths and are designed to prepare Christians for the Advent season. Candles in each window are meant to demonstrate the fact that Christians believe that Jesus Christ is the ultimate light of the world.

Christmas lights and banners may be hung along streets, music played from speakers, and Christmas trees placed in prominent places. It is common in many parts of the world for town squares and consumer shopping areas to sponsor and display decorations. Rolls of brightly coloured paper with secular or religious Christmas motifs are manufactured to wrap gifts. In some countries, Christmas decorations are traditionally taken down on the Twelfth Night.

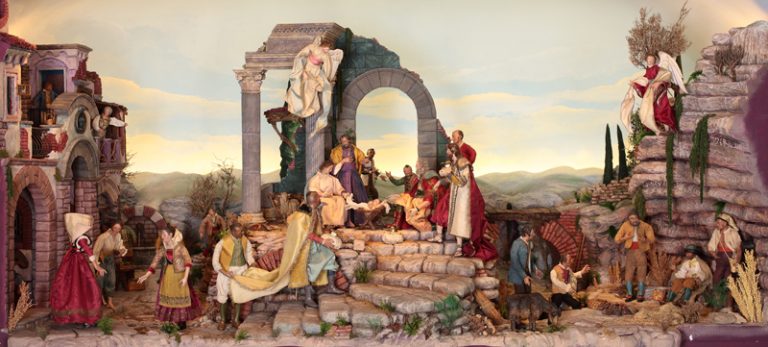

A typical Neapolitan Nativity scene by unknown.

This Eighteenth-century nativity scene painting is also known as a presepe or presepio and can be found at the Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art in Bilbao, Spain.

Local creches are renowned for their ornate decorations and symbolic figurines, often mirroring daily life.

A Christmas tree and presents.

The official White House Christmas tree for 1962 by Robert Knudsen.

The official White House Christmas tree above is in the entrance hall. It is usually located in the Blue Room, this was one of a few instances since 1961 where the tree has been displayed here.

It was presented by President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy at the Christmas Reception on the 12th of December, 1962 at the White House, U.S.A.

The Christ Candle in the centre of an Advent wreath.

This is traditionally lit in many church services. This one is in the chancel of Broadway United Methodist Church, located in New Philadelphia, U.S.A.

The Advent wreath consists of four coloured candles of the same size, arranged around a larger white Christ candle.

Nativity Play

For the Christian celebration of Christmas, the viewing of the Nativity play is one of the oldest Christmastime traditions, with the first reenactment of the Nativity of Jesus taking place in 1223 A.D. In that year, Francis of Assisi assembled a Nativity scene outside of his church in Italy and children sung Christmas carols celebrating the birth of Jesus. Each year, this grew larger and people travelled from afar to see Francis’ depiction of the Nativity of Jesus that came to feature drama and music. Nativity plays eventually spread throughout all of Europe, where they remain popular. Christmas Eve and Christmas Day church services often came to feature Nativity plays, as did schools and theatres. In France, Germany, Mexico and Spain, Nativity plays are often reenacted outdoors in the streets.

Read more about Nativity Play here.

Children in Oklahoma reenact a Nativity play.

These children are performing their nativity play in 2007 at the First Presbyterian Church in Edmond, Oklahoma, U.S.A.

Music And Carols

The earliest extant specifically Christmas hymns appear in fourth-century Rome. Latin hymns such as Veni redemptor gentium, written by Ambrose, Archbishop of Milan, were austere statements of the theological doctrine of the Incarnation in opposition to Arianism. Corde natus ex Parentis (Of the Father’s love begotten) by the Spanish poet Prudentius (died 413) is still sung in some churches today. In the 9th and 10th centuries, the Christmas Sequence or Prose was introduced in North European monasteries, developing under Bernard of Clairvaux into a sequence of rhymed stanzas. In the 12th century the Parisian monk Adam of St. Victor began to derive music from popular songs, introducing something closer to the traditional Christmas carol. Christmas carols in English appear in a 1426 work of John Awdlay who lists twenty-five “caroles of Cristemas”, probably sung by groups of wassailers, who went from house to house.

Read more about Music And Carols here.

Christmas carolers in Jersey.

Child singers in Bucharest by unknown.

This picture is from 1842 and depicts the singers carrying a star with an icon of a saint on it.

Christmas Food

A special Christmas family meal is traditionally an important part of the holiday celebration, and the food that is served varies greatly from country to country. Some regions have special meals for Christmas Eve, such as Sicily, where 12 kinds of fish are served. In the United Kingdom and countries influenced by its traditions, a standard Christmas meal usually includes turkey, goose or other large bird, gravy, potatoes, vegetables, sometimes bread, cider or some other alcoholic drink for the adults. Special desserts are also prepared, such as Christmas pudding, mince pies, Christmas cake, Panettone and a Yule log cake. A traditional Christmas meal in Central Europe features fried carp or other fish.

Read more about Christmas Food here.

A Christmas dinner setting.

Christmas Cards

Christmas cards are illustrated messages of greeting exchanged between friends and family members during the weeks preceding Christmas Day. The traditional greeting reads wishing you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year, much like that of the first commercial Christmas card, produced by Sir Henry Cole in London in 1843. The custom of sending them has become popular among a wide cross-section of people with the emergence of the modern trend towards exchanging E-cards.

Christmas cards are purchased in considerable quantities and feature artwork, is commercially designed and relevant to the season. The content of the design might relate directly to the Christmas narrative, with depictions of the Nativity of Jesus, or Christian symbols such as the Star of Bethlehem, or a white dove, which can represent both the Holy Spirit and Peace on Earth. Other Christmas cards are more secular and can depict Christmas traditions, mythical figures such as Father Christmas, objects directly associated with Christmas such as candles, holly, and baubles, or a variety of images associated with the season, such as Christmastide activities, snow scenes, and the wildlife of the northern winter.

Some prefer cards with a poem, prayer, or Biblical verse, while others distance themselves from religion with an all-inclusive Season’s greetings.

Read more about Christmas Cards here.

A Christmas postcard with Father Christmas and some of his reindeer by unknown.

This card was published by the Souvenir Post Card Company in New York, U.S.A. in 1907.

Christmas Stamps

A number of nations have issued commemorative stamps at Christmastide. Postal customers will often use these stamps to mail Christmas cards, and they are popular with philatelists. These stamps are regular postage stamps, unlike Christmas seals, and are valid for postage year-round. They usually go on sale sometime between early October and early December and are printed in considerable quantities.

Read more about Christmas Stamps here.

Christmas Gifts

The exchanging of gifts is one of the core aspects of the modern Christmas celebration, making it the most profitable time of year for retailers and businesses throughout the world. On Christmas, people exchange gifts based on the Christian tradition associated with Saint Nicholas, and the gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh which were given to the baby Jesus by the Magi. The practice of gift giving in the Roman celebration of Saturnalia may have influenced Christian customs, but on the other hand the Christian core dogma of the Incarnation, however, solidly established the giving and receiving of gifts as the structural principle of that recurrent yet unique event, because it was the Biblical Magi, together with all their fellow men, who received the gift of God through man’s renewed participation in the divine life. However, Thomas J. Talley holds that the Roman Emperor Aurelian placed the alternate festival on December the 25th in order to compete with the growing rate of the Christian Church, which had already been celebrating Christmas on that date first.

Read more about Christmas Gifts here.

Christmas gifts under a Christmas tree.

Gift-Bearing Figures

Several figures are associated with Christmas and the seasonal giving of gifts. Among these, the best known of these figures today is the red-dressed Father Christmas (more well-known in the United Kingdom although the American term Santa Claus is becoming more popular. Amongst many names around the world, he is known as Pere Noel, Joulupukki, Babbo Natale, Ded Moroz and tomte. The Scandinavian tomte (also called nisse) is sometimes depicted as a gnome instead of Santa Claus.

The name Santa Claus can be traced back to the Dutch Sinterklaas (Saint Nicholas). Nicholas was a 4th-century Greek bishop of Myra, a city in the Roman province of Lycia, whose ruins are 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from modern Demre in southwest Turkey. Among other saintly attributes, he was noted for the care of children, generosity, and the giving of gifts. His feast day, December the 6th, came to be celebrated in many countries with the giving of gifts.

Saint Nicholas traditionally appeared in bishop’s attire, accompanied by helpers, inquiring about the behaviour of children during the past year before deciding whether they deserved a gift or not. By the 13th century, Saint Nicholas was well known in the Netherlands, and the practice of gift-giving in his name spread to other parts of central and southern Europe. At the Reformation in 16th- and 17th-century Europe, many Protestants changed the gift bringer to the Christ Child or Christkindl, corrupted in English to Kris Kringle, and the date of giving gifts changed from December the 6th to Christmas Eve.

The modern popular image of Father Christmas, however, was created in the United States, and in particular in New York. The transformation was accomplished with the aid of notable contributors including Washington Irving and the German-American cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840 – 1902). Following the American Revolutionary War, some of the inhabitants of New York City sought out symbols of the city’s non-English past. New York had originally been established as the Dutch colonial town of New Amsterdam and the Dutch Sinterklaas tradition was reinvented as Saint Nicholas.

Current tradition in several Latin American countries (such as Venezuela and Colombia) holds that while Father Christmas makes the toys, he then gives them to Baby Jesus, who is the one who delivers them to the children’s homes, a reconciliation between traditional religious beliefs and the iconography of Santa Claus imported from the United States.

In South Tyrol (Italy), Austria, Czech Republic, Southern Germany, Hungary, Liechtenstein, Slovakia, and Switzerland, the Christkind (Jezisek in Czech, Jezuska in Hungarian and Jezisko in Slovak) brings the presents. Greek children get their presents from Saint Basil on New Year’s Eve, the eve of that saint’s liturgical feast. The German St. Nikolaus is not identical to the Weihnachtsmann (who is the German version of Father Christmas). St. Nikolaus wears a bishop’s dress and still brings small gifts (usually candies, nuts, and fruits) on December the 6th and is accompanied by Knecht Ruprecht. Although many parents around the world routinely teach their children about Father Christmas and other gift bringers, some have come to reject this practice, considering it deceptive.

Multiple gift-giver figures exist in Poland, varying between regions and individual families. St Nicholas (Swiety Mikolaj) dominates Central and North-East areas, the Starman (Gwiazdor) is most common in Greater Poland, Baby Jesus (Dzieciątko) is unique to Upper Silesia, with the Little Star (Gwiazdka) and the Little Angel (Aniołek) being common in the South and the South-East. Grandfather Frost (Dziadek Mroz) is less commonly accepted in some areas of Eastern Poland. It is worth noting that across all of Poland, St Nicholas is the gift giver on Saint Nicholas Day on December the 6th.

You can read a well-known poem about St. Nicholas here.

Read more about Gift-Bearing Figures here.

Saint Nicholas.

See Also

Christmas in July – Second Christmas celebration.

Christmas Peace – Finnish tradition.

Christmas Sunday – Sunday after Christmas.

List of Christmas novels – Christmas as depicted in literature.

Little Christmas – Alternative title for 6 January.

Nochebuena – Evening or entire day before Christmas Day.

Mithraism in comparison with other belief systems.

Christmas by medium – Christmas represented in different media.

Blog Posts

Links

Liliboas on iStock. The image shown at the top of this page of a Christmas tree and presents is the copyright of Liliboas. You can find more great work from the photographer Lili and lots more free stock photos at iStock.

The image above of a nativity scene made with Christmas lights is the copyright of Wikipedia user Crumpled Fire. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.0).

The image above of the Nativity by unknown comes via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of the Coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas of 800 by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld comes via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of the Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas by Josiah King comes via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of the Queen’s Christmas Tree at Windsor Castle by Joseph Lionel Williams comes via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of a Norwegian Christmas by Adolph Tidemand comes via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of the Christmas visit by unknown comes via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of Adoration of the Shepherds by Gerard van Honthorst comes via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of the Nativity of Christ by Herrad of Landsberg comes via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of Christmas at the Annunciation Church in Nazareth is the copyright of Wikipedia user Israel Press and Photo Agency. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The image above of a typical Neapolitan Nativity scene by unknown comes from the Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The image above of the official White House Christmas tree for 1962 by Robert Knudsen comes from the Kennedy Library via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of the Christ Candle in the centre of an Advent wreath is the copyright of Wikipedia user PFAStudent. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of children in Oklahoma reenact a Nativity play is the copyright of Wikipedia user Wesley Fryer. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.0).

The image above of Christmas carolers in Jersey is copyright of Wikipedia user Man vyi and is in the public domain.

The image above of a Christmas dinner setting is the copyright of Wikipedia user Austin McGee. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.0).

The image above of a Christmas postcard with Father Christmas and some of his reindeer by unknown comes via Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

The image above of Christmas gifts under a Christmas tree is the copyright of Wikipedia user Kelvin Kay. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.0).

The image above of Saint Nicholas is the copyright of Wikipedia user CrazyPhunk. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).