You can download all of the fourteen fantasy books in the Oz series by L. Frank Baum via Project Gutenberg by clicking on The Oz Series By L. Frank Baum link in Blog Posts below.

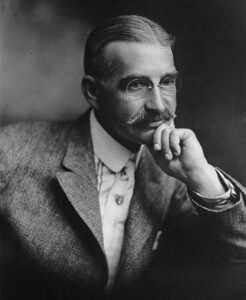

About L. Frank Baum

Lyman Frank Baum was an American author best known for his children’s books, particularly The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and its sequels. He wrote 14 novels in the Oz series, plus 41 other novels (not including four lost, unpublished novels), 83 short stories, over 200 poems, and at least 42 scripts. He made numerous attempts to bring his works to the stage and screen; the 1939 adaptation of the first Oz book became a landmark of 20th-century cinema.

Born and raised in upstate New York, Baum moved west after an unsuccessful stint as a theatre producer and playwright. He and his wife opened a store in South Dakota and he edited and published a newspaper. They then moved to Chicago, where he worked as a newspaper reporter and published children’s literature, coming out with the first Oz book in 1900. While continuing his writing, among his final projects he sought to establish a movie studio focused on children’s films in Los Angeles, California.

His works anticipated such later commonplaces as television, augmented reality, laptop computers (The Master Key), wireless telephones (Tik-Tok of Oz), women in high-risk and action-heavy occupations (Mary Louise in the Country), and the ubiquity of clothes advertising (Aunt Jane’s Nieces at Work).

L. Frank Baum’s Childhood And Early Life

Baum was born in Chittenango, New York, in 1856 into a devout Methodist family. He had German, Scots-Irish, and English ancestry. He was the seventh of nine children of Cynthia Ann (née Stanton) and Benjamin Ward Baum, only five of whom survived into adulthood. “Lyman” was the name of his father’s brother, but he always disliked it and preferred his middle name, Frank.

His father succeeded in many businesses, including barrel-making, oil drilling in Pennsylvania, and real estate. Baum grew up on his parents’ expansive estate called Rose Lawn, which he fondly recalled as a sort of paradise. Rose Lawn was located in Mattydale, New York. Frank was a sickly, dreamy child, tutored at home with his siblings. From the age of 12, he spent two miserable years at Peekskill Military Academy but, after being severely disciplined for daydreaming, he had a possibly psychogenic heart attack and was allowed to return home.

Baum started writing early in life, possibly prompted by his father buying him a cheap printing press. He had always been close to his younger brother Henry (Harry) Clay Baum, who helped in the production of The Rose Lawn Home Journal. The brothers published several issues of the journal, including advertisements from local businesses, which they gave to family and friends for free. By the age of 17, Baum established a second amateur journal called The Stamp Collector, printed an 11-page pamphlet called Baum’s Complete Stamp Dealers’ Directory, and started a stamp dealership with friends.

At 20, Baum took on the national craze of breeding fancy poultry. He specialized in raising the Hamburg chicken. In March 1880, he established a monthly trade journal, The Poultry Record, and in 1886, when Baum was 30 years old, his first book was published: The Book of the Hamburgs: A Brief Treatise upon the Mating, Rearing, and Management of the Different Varieties of Hamburgs.

Baum had a flair for being the spotlight of fun in the household, including during times of financial difficulties. His selling of fireworks made the Fourth of July memorable. His skyrockets, Roman candles, and fireworks filled the sky, while many people around the neighborhood would gather in front of the house to watch the displays. Christmas was even more festive. Baum dressed as Santa Claus for the family. His father would place the Christmas tree behind a curtain in the front parlor so that Baum could talk to everyone while he decorated the tree without people managing to see him. He maintained this tradition all his life.

L. Frank Baum served for two years as a cadet at the Peekskill Military School, which overlooked the Hudson. He was about 12 years old in this 1868 photograph.

L. Frank Baum’s Career

Theatre

Baum embarked on his lifetime infatuation—and wavering financial success—with the theatre. A local theatrical company duped him into replenishing their stock of costumes on the promise of leading roles coming his way. Disillusioned, Baum left the theatre—temporarily—and went to work as a clerk in his brother-in-law’s dry goods company in Syracuse. This experience may have influenced his story “The Suicide of Kiaros”, first published in the literary journal The White Elephant. A fellow clerk one day had been found locked in a storeroom dead, probably from suicide.

Baum could never stay away long from the stage. He performed in plays under the stage names of Louis F. Baum and George Brooks. In 1880, his father built him a theatre in Richburg, New York, and Baum set about writing plays and gathering a company to act in them. The Maid of Arran proved a modest success, a melodrama with songs based on William Black’s novel A Princess of Thule. Baum wrote the play and composed songs for it (making it a prototypical musical, as its songs relate to the narrative), and acted in the leading role. His aunt Katharine Gray played his character’s aunt. She was the founder of Syracuse Oratory School, and Baum advertised his services in her catalogue to teach theatre, including stage business, playwriting, directing, translating (French, German, and Italian), revision, and operettas.

On November 9, 1882, Baum married Maud Gage, a daughter of Matilda Joslyn Gage, a famous women’s suffrage and feminist activist. While Baum was touring with The Maid of Arran, the theatre in Richburg caught fire during a production of Baum’s ironically titled parlour drama Matches, destroying the theatre as well as the only known copies of many of Baum’s scripts, including Matches, as well as costumes.

The South Dakota Years

In July 1888, Baum and his wife moved to Aberdeen, Dakota Territory where he opened a store called “Baum’s Bazaar”. His habit of giving out wares on credit led to the eventual bankrupting of the store, so Baum turned to editing the local newspaper The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer where he wrote the column Our Landlady. Following the death of Sitting Bull at the hands of Indian agency police, Baum urged the wholesale extermination of all America’s native peoples in a column that he wrote on December 20, 1890. He wrote:

“The Pioneer has before declared that our only safety depends upon the total extirmination [sic] of the Indians. Having wronged them for centuries, we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth”.

Baum’s description of Kansas in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is based on his experiences in drought-ridden South Dakota. During much of this time, Matilda Joslyn Gage was living in the Baum household. While Baum was in South Dakota, he sang in a quartet which included James Kyle, who became one of the first Populist (People’s Party) Senators in the U.S.

Writing

Baum’s newspaper failed in 1891, and he, Maud, and their four sons moved to the Humboldt Park section of Chicago, where Baum took a job reporting for the Evening Post. Beginning in 1897, he founded and edited a magazine called The Show Window, later known as the Merchants Record and Show Window, which focused on store window displays, retail strategies and visual merchandising. The major department stores of the time created elaborate Christmas time fantasies, using clockwork mechanisms that made people and animals appear to move. The former Show Window magazine is still currently in operation, now known as VMSD magazine (visual merchandising + store design), based in Cincinnati. In 1900, Baum published a book about window displays in which he stressed the importance of mannequins in drawing customers. He also had to work as a travelling salesman.

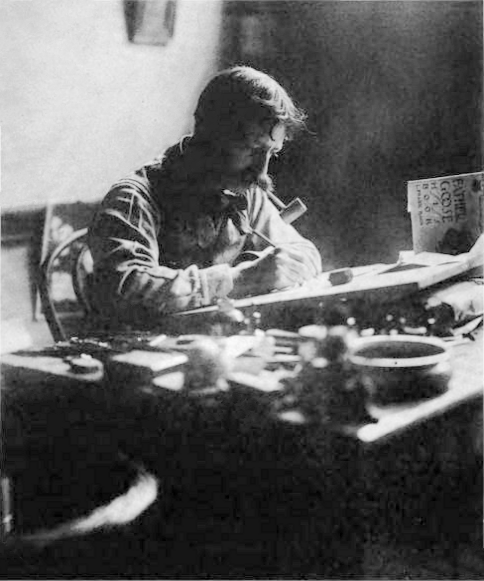

In 1897, he wrote and published Mother Goose in Prose, a collection of Mother Goose rhymes written as prose stories and illustrated by Maxfield Parrish. Mother Goose was a moderate success and allowed Baum to quit his sales job (which had had a negative impact on his health). In 1899, Baum partnered with illustrator W. W. Denslow to publish Father Goose, His Book, a collection of nonsense poetry. The book was a success, becoming the best-selling children’s book of the year.

In 1897 Mother Goose by L. Frank Baum and Maxfield Parrish was used to promote a breakfast cereal (part 1 of 12 as a free premium).

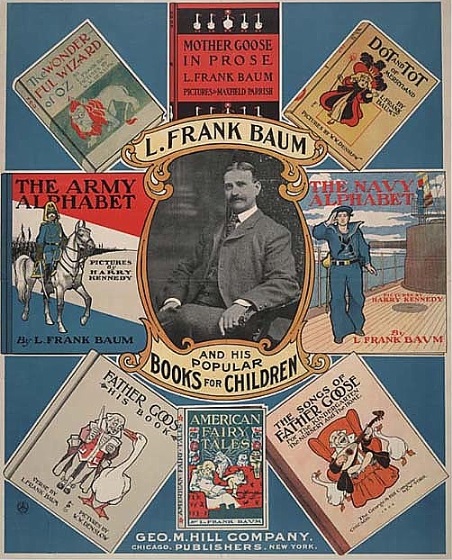

Promotional Poster for Popular Books For Children, circa 1901.

W. W. Denslow in 1900.

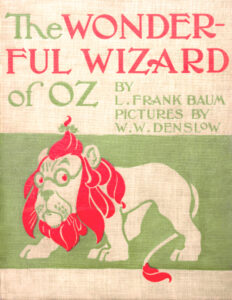

The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz

In 1900, Baum and Denslow (with whom he shared the copyright) published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz to much critical acclaim and financial success. The book was the best-selling children’s book for two years after its initial publication. Baum went on to write thirteen more novels based on the places and people of the Land of Oz.

The Wizard Of Oz: Fred R. Hamlin’s Musical Extravaganza

Two years after Wizard‘s publication, Baum and Denslow teamed up with composer Paul Tietjens and director Julian Mitchell to produce a musical stage version of the book under Fred R. Hamlin. Baum and Tietjens had worked on a musical of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1901 and based closely upon the book, but it was rejected. This stage version opened in Chicago in 1902 (the first to use the shortened title, The Wizard of Oz), then ran on Broadway for 293 stage nights from January to October 1903. It returned to Broadway in 1904, where it played from March to May and again from November to December. It successfully toured the United States with much of the same cast, as was done in those days, until 1911, and then became available for amateur use. The stage version starred Anna Laughlin as Dorothy Gale, alongside David C. Montgomery and Fred Stone as the Tin Woodman and Scarecrow respectively, which shot the pair to instant fame.

The stage version differed quite a bit from the book and was aimed primarily at adults. Toto was replaced with Imogene the Cow, and Tryxie Tryfle (a waitress) and Pastoria (a streetcar operator) were added as fellow cyclone victims. The Wicked Witch of the West was eliminated entirely in the script, and the plot became about how the four friends were allied with the usurping Wizard and were hunted as traitors to Pastoria II, the rightful King of Oz. It is unclear how much control or influence Baum had on the script; it appears that many of the changes were written by Baum against his wishes due to contractual requirements with Hamlin. Jokes in the script, mostly written by Glen MacDonough, called for explicit references to President Theodore Roosevelt, Senator Mark Hanna, Rev. Andrew Danquer, and oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller. Although the use of the script was rather free-form, the line about Hanna was ordered dropped as soon as Hamlin got word of his death in 1904.

Beginning with the success of the stage version, most subsequent versions of the story, including newer editions of the novel, have been titled The Wizard of Oz, rather than using the full, original title. In more recent years, restoring the full title has become increasingly common, particularly to distinguish the novel from the Hollywood film.

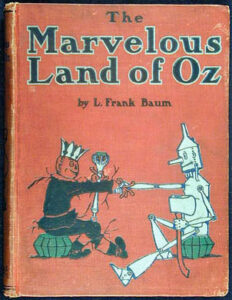

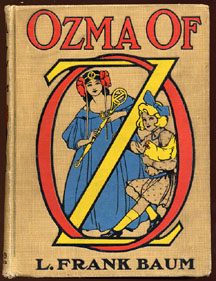

Baum wrote a new Oz book, The Marvelous Land of Oz, with a view to making it into a stage production, which was titled The Woggle-Bug, but Montgomery and Stone baulked at appearing when the original was still running. The Scarecrow and Tin Woodman were then omitted from this adaptation, which was seen as a self-rip-off by critics and proved to be a major flop before it could reach Broadway. He also worked for years on a musical version of Ozma of Oz, which eventually became The Tik-Tok Man of Oz. This did fairly well in Los Angeles, but not well enough to convince producer Oliver Morosco to mount a production in New York. He also began a stage version of The Patchwork Girl of Oz, but this was ultimately realized as a film.

A 1903 poster of Dave Montgomery as the Tin Man in Fred R. Hamlin’s musical stage version of The Wizard Of Oz.

Later Life And Work

With the success of Wizard on page and stage, Baum and Denslow hoped for further success and published Dot and Tot of Merryland in 1901. The book was one of Baum’s weakest, and its failure further strained his faltering relationship with Denslow. It was their last collaboration. Baum worked primarily with John R. Neill on his fantasy work beginning in 1904, but Baum met Neill a few times (all before he moved to California) and often found Neill’s art not humorous enough for his liking. He was particularly offended when Neill published The Oz Toy Book: Cut-outs for the Kiddies without authorization.

Baum reportedly designed the chandeliers in the Crown Room of the Hotel del Coronado; however, that attribution has yet to be corroborated. Several times during the development of the Oz series, Baum declared that he had written his last Oz book and devoted himself to other works of fantasy fiction based in other magical lands, including The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus and Queen Zixi of Ix. However, he returned to the series each time, persuaded by popular demand, letters from children, and the failure of his new books. Even so, his other works remained very popular after his death, with The Master Key appearing on St. Nicholas Magazine’s survey of readers’ favourite books well into the 1920s.

In 1905, Baum declared plans for an Oz amusement park. In an interview, he mentioned buying “Pedloe Island” off the coast of California to turn it into an Oz park. However, there is no evidence that he purchased such an island, and no one has ever been able to find any island whose name even resembles Pedloe in that area. Nevertheless, Baum stated to the press that he had discovered a Pedloe Island off the coast of California and that he had purchased it to be “the Marvelous Land of Oz,” intending it to be “a fairy paradise for children.” Eleven-year-old Dorothy Talbot of San Francisco was reported to be ascendant to the throne on March 1, 1906, when the Palace of Oz was expected to be completed. Baum planned to live on the island, with administrative duties handled by the princess and her all-child advisers. Plans included statues of the Scarecrow, Tin Woodman, Jack Pumpkinhead, and H.M. Woggle-Bug, T.E. Baum abandoned his Oz park project after the failure of The Woggle-Bug, which was playing at the Garrick Theatre in 1905.

Because of his lifelong love of theatre, he financed elaborate musicals, often to his financial detriment. One of Baum’s worst financial endeavours was his The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays (1908), which combined a slideshow, film, and live actors with a lecture by Baum as if he were giving a travelogue to Oz. However, Baum ran into trouble and could not pay his debts to the company that produced the films. He did not get back to a stable financial situation for several years, after he sold the royalty rights to many of his earlier works, including The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. This resulted in the M.A. Donahue Company publishing cheap editions of his early works with advertising which purported that Baum’s newer output was inferior to the less expensive books that they were releasing. He claimed bankruptcy in August 1911. However, Baum had shrewdly transferred most of his property into Maud’s name, except for his clothing, his typewriter, and his library (mostly of children’s books, such as the fairy tales of Andrew Lang, whose portrait he kept in his study)—all of which, he successfully argued, was essential to his occupation. Maud handled the finances anyway, and thus Baum lost much less than he could have.

Read more about Later Life And Work here.

L. Frank Baum and characters in The Fairylogue and Radio Plays in 1908.

Death

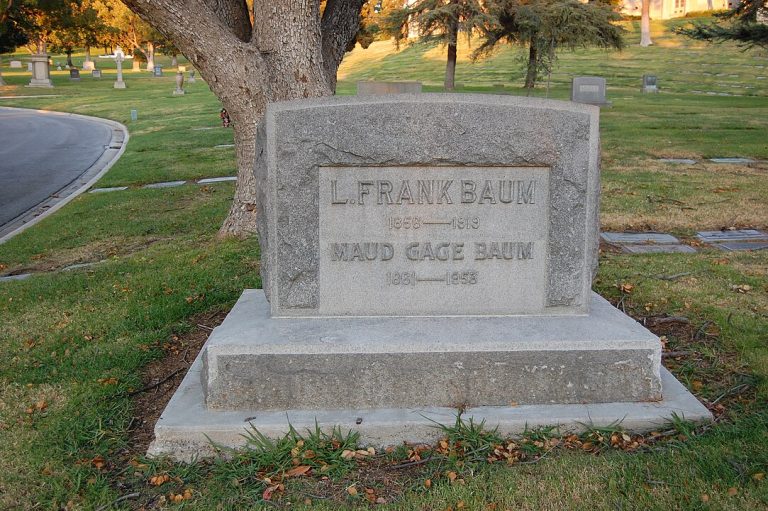

On May 5, 1919, Baum suffered a stroke, slipped into a coma and died the following day, at the age of 62. His last words were spoken to his wife during a brief period of lucidity: “Now we can cross the Shifting Sands.” He was buried in Glendale’s Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery.

His final Oz book, Glinda of Oz, was published on July 10, 1920, a year after his death. The Oz series was continued long after his death by other authors, notably Ruth Plumly Thompson, who wrote an additional twenty-one Oz books.

Frank L. Baum’s grave at Forest Lawn Cemetery, Glendale, California in 2011.

Blog Posts

Books: The Oz Series By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Marvelous Land Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Ozma Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Dorothy And The Wizard In Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Road To Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Emerald City Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Patchwork Girl Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Tik-Tok Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Scarecrow Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Rinkitink In Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Lost Princess Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Tin Woodman Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Magic Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Glinda Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: Queer Visitors From The Marvelous Land Of Oz.

Books: Little Wizard Stories Of Oz.

Books: Queer Visitors From The Marvelous Land Of Oz By L. Frank Baum.

Books: The Woggle-Bug Book By L. Frank Baum.

Notes And Links

The image above of L. Frank Baum shown at the top of this page is copyright of George Steckel.

The image above of L. Frank Baum as a cadet at the Peekskill Military School is copyright unknown.

The image above of Mother Goose by L. Frank Baum and Maxfield Parrish is copyright unknown.

The image above of the Promotional Poster for Popular Books For Children, circa 1901 is copyright unknown.

The image above of W. W. Denslow in 1900 is copyright unknown.

The image above of a 1903 poster of Dave Montgomery as the Tin Man in Fred R. Hamlin’s musical stage version of The Wizard Of Oz is copyright of U.S. Lithograph Co.

All the above images are in the Public Domain via Wikipedia.

The image above of Frank L. Baum’s grave at Forest Lawn Cemetery, Glendale, California in 2011 is copyright of Wikipedia user Meribona. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Project Gutenberg – Project Gutenberg is an online library of free e-books and was the first provider of free electronic books. Michael Hart, the founder of Project Gutenberg, invented e-books in 1971 and his memory continues to inspire the creation of them and related content today.

Creative Commons – Official website. They offer better sharing, advancing universal access to knowledge and culture, and fostering creativity, innovation, and collaboration.

The Wonderful Wiki of Oz – Official website. A wonderful and welcoming encyclopedia of all things Oz that anyone can edit or contribute Oz-related information and Oz facts to enjoy.

The Oz Archive on Facebook – Archiving and celebrating the legacy of Oz.

The Oz Archive on Twitter – Archiving and celebrating the legacy of Oz.

The Oz Archive on Instagram – Archiving and celebrating the legacy of Oz.

The Oz Archive on TikTok – Archiving and celebrating the legacy of Oz.