I don’t practice Buddhism but I have been interested in it for a long time now. It is the only religion I have time for because it truly promotes peace without the need for an imaginary man in the sky and the fear and anything that is not peaceful associated with him.

About Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddha Dharma or Dharmavinaya (translated means doctrines and disciplines), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on a series of original teachings attributed to Gautama Buddha. Originating in ancient India as a movement professing śramaṇa between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, it gradually spread throughout much of Asia via the Silk Road. Presently, it is the world’s fourth-largest religion, with over 520 million followers (Buddhists) who comprise seven percent of the global population. Buddhism encompasses a variety of traditions, beliefs, and spiritual practices that are largely based on the Buddha’s teachings and their resulting interpreted philosophies.

As expressed in the Four Noble Truths of the Buddha, the goal of Buddhism is to overcome the suffering (duḥkha) caused by desire (taṇhā) and ignorance (avidyā) of reality’s true nature, including impermanence (anitya) and non-self (anātman). Most Buddhist traditions emphasize transcending the individual self through the attainment of nirvāṇa (translated means quenching) or by following the path of Buddhahood, ending the cycle of death and rebirth (saṃsāra). Buddhist schools vary in their interpretation of the paths to liberation (mārga) as well as the relative importance and canonicity assigned to various Buddhist texts, and their specific teachings and practices. Widely observed practices include meditation; observance of moral precepts; monasticism; taking refuge in the Buddha, the dharma, and the saṅgha; and the cultivation of perfections (pāramitā).

Two major extant branches of Buddhism are generally recognized by scholars: Theravāda (translated means School of the Elders) and Mahāyāna (translated means Great Vehicle). The Theravāda branch has a widespread following in Sri Lanka as well as in Southeast Asia (namely Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia). The Mahāyāna branch (which includes the traditions of Zen, Pure Land, Nichiren, Tiantai, Tendai, and Shingon) is predominantly practiced in Nepal, Bhutan, China, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. Additionally, Vajrayāna (translated means Indestructible Vehicle), a body of teachings attributed to Indian adepts, may be viewed as a separate branch or an aspect of the Mahāyāna tradition. Tibetan Buddhism, which preserves the Vajrayāna teachings of eighth-century India, is practised in the Himalayan states as well as in Mongolia and Russian Kalmykia. Historically, until the early 2nd millennium, Buddhism was widely practised in the Indian subcontinent; it also had a foothold to some extent in other places such as Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and the Philippines.

For a more detailed timeline of Buddhism click here.

Dharma Wheel

The Dharmachakra is a sacred symbol which represents Buddhism and its traditions.

Vesak Decorations In Sri Lanka

These lanterns are used in the Vesak Festival, which celebrates the birth, enlightenment and Parinirvana of Gautama Buddha.

The History Of Buddhism

Historical Roots

Historically, the roots of Buddhism lie in the religious thought of Iron Age India around the middle of the first millennium BCE This was a period of great intellectual ferment and socio-cultural change known as the Second urbanisation, marked by the growth of towns and trade, the composition of the Upanishads and the historical emergence of the Śramaṇa traditions.

New ideas developed both in the Vedic tradition in the form of the Upanishads and outside of the Vedic tradition through the Śramaṇa movements. The term Śramaṇa refers to several Indian religious movements parallel to but separate from the historical Vedic religion, including Buddhism, Jainism and others such as Ājīvika.

Several Śramaṇa movements are known to have existed in India before the 6th century BCE (pre-Buddha, pre-Mahavira), and these influenced both the āstika and nāstika traditions of Indian philosophy. According to Martin Wilshire, the Śramaṇa tradition evolved in India over two phases, namely Paccekabuddha and Savaka phases, the former being the tradition of individual ascetics and the latter of disciples, and that Buddhism and Jainism ultimately emerged from these. Brahmanical and non-Brahmanical ascetic groups shared and used several similar ideas but the Śramaṇa traditions also drew upon already established Brahmanical concepts and philosophical roots, states Wiltshire, to formulate their own doctrines. Brahmanical motifs can be found in the oldest Buddhist texts, using them to introduce and explain Buddhist ideas. For example, prior to Buddhist developments, the Brahmanical tradition internalised and variously reinterpreted the three Vedic sacrificial fires as concepts such as Truth, Rite, Tranquility or Restraint. Buddhist texts also refer to the three Vedic sacrificial fires, reinterpreting and explaining them as ethical conduct.

The Śramaṇa religions challenged and broke with the Brahmanic tradition on core assumptions such as Atman (soul, self), Brahman, and the nature of the afterlife, and they rejected the authority of the Vedas and Upanishads. Buddhism was one among several Indian religions that did so.

Read more about The History Of Buddhism here.

Mahākāśyapa

Mahākāśyapa meets an Ājīvika ascetic, one of the common Śramaṇa groups in ancient India.

Indian Buddhism

The history of Indian Buddhism may be divided into five periods: Early Buddhism (occasionally called pre-sectarian Buddhism), Nikaya Buddhism or Sectarian Buddhism: The period of the early Buddhist schools, Early Mahayana Buddhism, Late Mahayana, and the era of Vajrayana or the Tantric Age.

Read more about Indian Buddhism here.

Pre-Sectarian Buddhism

According to Lambert Schmithausen Pre-sectarian Buddhism is “the canonical period prior to the development of different schools with their different positions.”

The early Buddhist Texts include the four principal Pali Nikāyas (and their parallel Agamas found in the Chinese canon) together with the main body of monastic rules, which survive in the various versions of the patimokkha. However, these texts were revised over time, and it is unclear what constitutes the earliest layer of Buddhist teachings. One method to obtain information on the oldest core of Buddhism is to compare the oldest extant versions of the Theravadin Pāli Canon and other texts. The reliability of the early sources, and the possibility to draw out a core of the oldest teachings, is a matter of dispute. According to Vetter, inconsistencies remain, and other methods must be applied to resolve those inconsistencies.

According to Schmithausen, three positions held by scholars of Buddhism can be distinguished:

“Stress on the fundamental homogeneity and substantial authenticity of at least a considerable part of the Nikayic materials;”

“Scepticism with regard to the possibility of retrieving the doctrine of earliest Buddhism;”

“Cautious optimism in this respect.”

Read more about Pre-Sectarian Buddhism here.

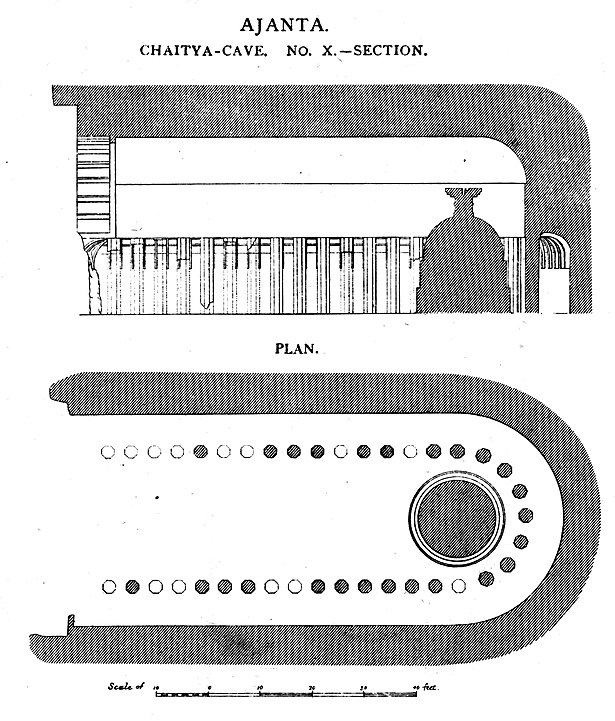

Ajanta Caves, Cave 10

Cave 10, is a first-period type chaitya worship hall with a stupa but no idols.

The Core Teachings

According to Mitchell, certain basic teachings appear in many places throughout the early texts, which has led most scholars to conclude that Gautama Buddha must have taught something similar to the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, Nirvana, the three marks of existence, the five aggregates, dependent origination, karma and rebirth.

According to N. Ross Reat, all of these doctrines are shared by the Theravada Pali texts and the Mahasamghika school’s Śālistamba Sūtra. A recent study by Bhikkhu Analayo concludes that the Theravada Majjhima Nikaya and Sarvastivada Madhyama Agama contain mostly the same major doctrines. Richard Salomon, in his study of the Gandharan texts (which are the earliest manuscripts containing early discourses), has confirmed that their teachings are “consistent with non-Mahayana Buddhism, which survives today in the Theravada school of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, but which in ancient times was represented by eighteen separate schools.”

However, some scholars argue that critical analysis reveals discrepancies among the various doctrines found in these early texts, which point to alternative possibilities for early Buddhism. The authenticity of certain teachings and doctrines has been questioned. For example, some scholars think that karma was not central to the teaching of the historical Buddha, while others disagree with this position. Likewise, there is scholarly disagreement on whether insight was seen as liberating in early Buddhism or whether it was a later addition to the practice of the four jhānas. Scholars such as Bronkhorst also think that the four noble truths may not have been formulated in earliest Buddhism, and did not serve in earliest Buddhism as a description of liberating insight. According to Vetter, the description of the Buddhist path may initially have been as simple as the term the middle way”. In time, this short description was elaborated, resulting in the description of the eightfold path.

Ashokan Era And The Early Schools

According to numerous Buddhist scriptures, soon after the parinirvāṇa (from Sanskrit: highest extinguishment) of Gautama Buddha, the first Buddhist council was held to collectively recite the teachings to ensure that no errors occurred in oral transmission. Many modern scholars question the historicity of this event. However, Richard Gombrich states that the monastic assembly recitations of the Buddha’s teaching likely began during Buddha’s lifetime, and they served a similar role in codifying the teachings.

The so-called Second Buddhist council resulted in the first schism in the Sangha. Modern scholars believe that this was probably caused when a group of reformists called Sthaviras (elders) sought to modify the Vinaya (monastic rule), and this caused a split with the conservatives who rejected this change, they were called Mahāsāṃghikas. While most scholars accept that this happened at some point, there is no agreement on the dating, especially if it dates to before or after the reign of Ashoka.

Buddhism may have spread only slowly throughout India until the time of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka (304 – 232 BCE), who was a public supporter of the religion. The support of Aśoka and his descendants led to the construction of more stūpas (such as at Sanchi and Bharhut), temples (such as the Mahabodhi Temple) and to its spread throughout the Maurya Empire and into neighbouring lands such as Central Asia and the island of Sri Lanka.

During and after the Mauryan period (322 – 180 BCE), the Sthavira community gave rise to several schools, one of which was the Thera vada school which tended to congregate in the south and another which was the Sarvāstivāda school, which was mainly in north India. Likewise, the Mahāsāṃghika groups also eventually split into different Sanghas. Originally, these schisms were caused by disputes over monastic disciplinary codes of various fraternities, but eventually, by about 100 CE if not earlier, schisms were being caused by doctrinal disagreements too.

Following (or leading up to) the schisms, each Saṅgha started to accumulate their own version of Tripiṭaka (triple basket of texts). In their Tripiṭaka, each school included the Suttas of the Buddha, and a Vinaya basket (disciplinary code) and some schools also added an Abhidharma basket which was text on detailed scholastic classification, summary and interpretation of the Suttas. The doctrine details in the Abhidharma of various Buddhist schools differ significantly, and these were composed starting about the third century BCE and through the 1st millennium CE.

Read more about Ashokan Era And The Early Schools here, here and here.

Sanchi Stupa Number 3

This Stupa is near Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, India.

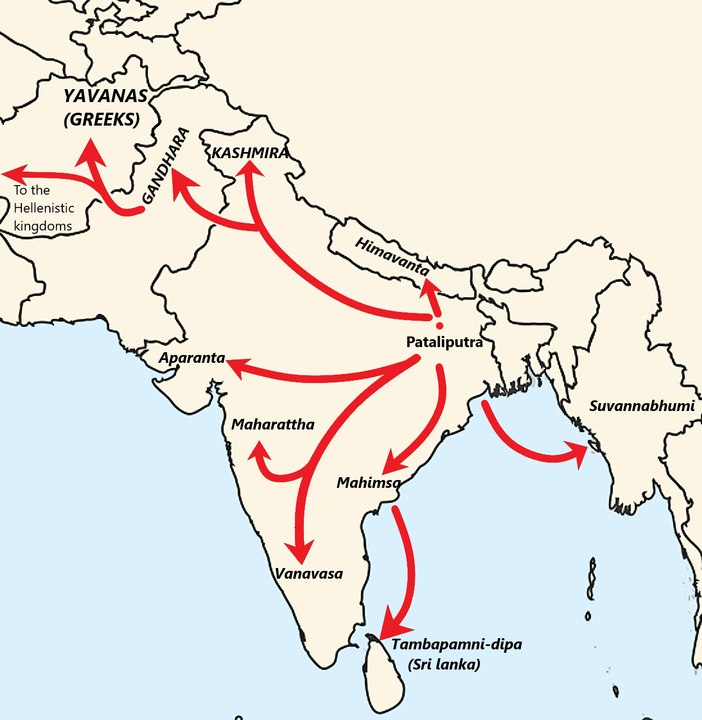

Buddhist Missions

Map of the Buddhist missions during the reign of Ashoka according to the Edicts of Ashoka. Sourced fromː Cousins, LS. “On the Vibhajjavadins. The Mahimsasaka, Dhammaguttaka, Kassapiya and Tambapanniya branches of the ancient Theriyas”, Buddhist Studies Review 18, 2 (2001), TABLE E.

Post-Ashokan Expansion

According to the edicts of Aśoka, the Mauryan emperor sent emissaries to various countries west of India to spread Dharma, particularly in eastern provinces of the neighbouring Seleucid Empire, and even farther to Hellenistic kingdoms of the Mediterranean. It is a matter of disagreement among scholars whether or not these emissaries were accompanied by Buddhist missionaries.

In central and west Asia, Buddhist influence grew, through Greek-speaking Buddhist monarchs and ancient Asian trade routes, a phenomenon known as Greco-Buddhism. An example of this is evidenced in Chinese and Pali Buddhist records, such as Milindapanha and the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhāra. The Milindapanha describes a conversation between a Buddhist monk and the 2nd-century BCE Greek king Menander, after which Menander abdicates and goes into monastic life in the pursuit of nirvana. Some scholars have questioned the Milindapanha version, expressing doubts about whether Menander was Buddhist or just favourably disposed to Buddhist monks.

The Kushan empire (30 – 375 CE) came to control the Silk Road trade through Central and South Asia, which brought them to interact with Gandharan Buddhism and the Buddhist institutions of these regions. The Kushans patronised Buddhism throughout their lands, and many Buddhist centres were built or renovated (the Sarvastivada school was particularly favoured), especially by Emperor Kanishka (128 – 151 CE). Kushan support helped Buddhism to expand into a world religion through their trade routes. Buddhism spread to Khotan, the Tarim Basin, and China, and eventually to other parts of the far east. Some of the earliest written documents of the Buddhist faith are the Gandharan Buddhist texts, dating from about the 1st century CE, and connected to the Dharmaguptaka school.

The Islamic conquest of the Iranian Plateau in the 7th century, followed by the Muslim conquests of Afghanistan and the later establishment of the Ghaznavid kingdom with Islam as the state religion in Central Asia between the 10th- and 12th century led to the decline and disappearance of Buddhism from most of these regions.

Read more about Post-Ashokan Expansion here.

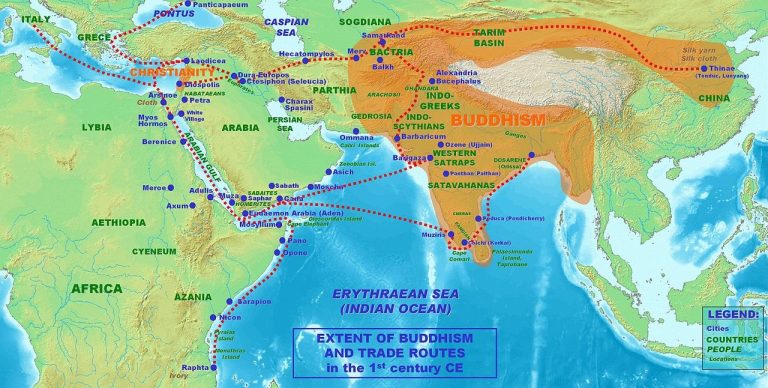

The Extent Of Buddhism And Trade

This map shows the extent of Buddhism and trade routes in the 1st century CE.

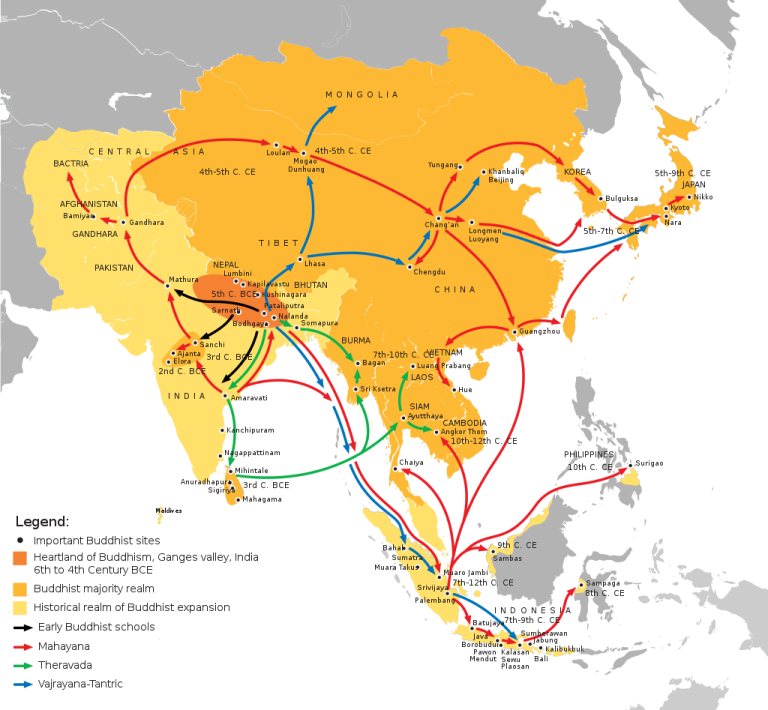

The Buddhist Expansion Throughout Asia

A map showing the expansion of Buddhism, originated from India in VI century BCE to the rest of Asia until the present.

Mahāyāna Buddhism

The origins of Mahāyāna (Great Vehicle) Buddhism are not well understood and there are various competing theories about how and where this movement arose. Theories include the idea that it began as various groups venerating certain texts or that it arose as a strict forest ascetic movement.

The first Mahāyāna works were written sometime between the 1st century BCE and the 2nd century CE. Much of the early extant evidence for the origins of Mahāyāna comes from early Chinese translations of Mahāyāna texts, mainly those of Lokakṣema. (2nd century CE). Some scholars have traditionally considered the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras to include the first versions of the Prajnaparamita series, along with texts concerning Akṣobhya, which were probably composed in the 1st century BCE in the south of India.

There is no evidence that Mahāyāna ever referred to a separate formal school or sect of Buddhism, with a separate monastic code (Vinaya), but rather that it existed as a certain set of ideals, and later doctrines, for bodhisattvas. Records written by Chinese monks visiting India indicate that both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna monks could be found in the same monasteries, with the difference that Mahāyāna monks worshipped figures of Bodhisattvas, while non-Mahayana monks did not.

Mahāyāna initially seems to have remained a small minority movement that was in tension with other Buddhist groups, struggling for wider acceptance. However, during the fifth and sixth centuries CE, there seems to have been a rapid growth of Mahāyāna Buddhism, which is shown by a large increase in epigraphic and manuscript evidence in this period. However, it still remained a minority in comparison to other Buddhist schools.

Mahāyāna Buddhist institutions continued to grow in influence during the following centuries, with large monastic university complexes such as Nalanda (established by the 5th-century CE Gupta emperor, Kumaragupta I) and Vikramashila (established under Dharmapala c. 783 to 820) becoming quite powerful and influential. During this period of Late Mahāyāna, four major types of thought developed: Mādhyamaka, Yogācāra, Buddha-nature (Tathāgatagarbha), and the epistemological tradition of Dignaga and Dharmakirti. According to Dan Lusthaus, Mādhyamaka and Yogācāra have a great deal in common, and the commonality stems from early Buddhism.

Read more about Mahāyāna Buddhism here.

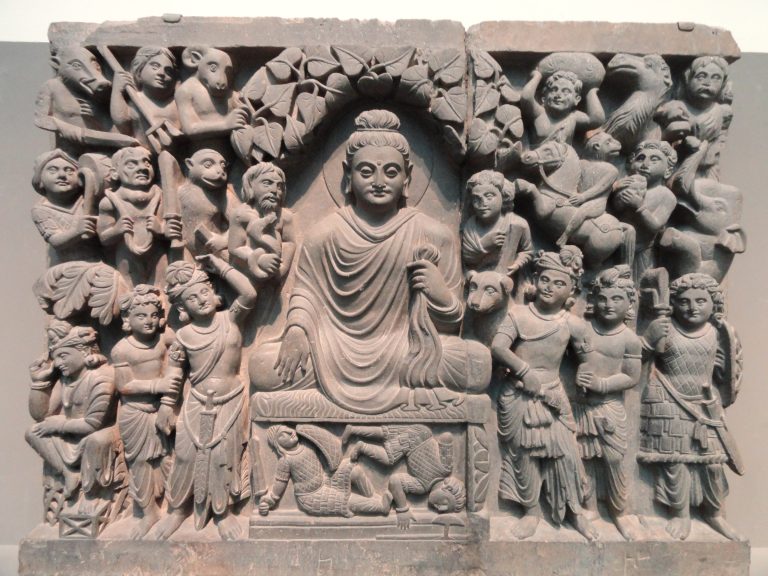

A Buddhist Triad

A Buddhist triad depicting (from left to right) a Kushan devotee, the Bodhisattva Maitreya, the Buddha, the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, and a Buddhist monk. Circa second–third-century from Guimet Museum, Paris, France.

Late Indian Buddhism And Tantra

During the Gupta period (4th – 6th centuries) and the empire of Harṣavardana (c. 590 – 647 CE), Buddhism continued to be influential in India, and large Buddhist learning institutions such as Nalanda and Valabahi Universities were at their peak. Buddhism also flourished under the support of the Pāla Empire (8th -12th centuries). Under the Guptas and Palas, Tantric Buddhism or Vajrayana developed and rose to prominence. It promoted new practices such as the use of mantras, dharanis, mudras, mandalas and the visualization of deities and Buddhas and developed a new class of literature, the Buddhist Tantras. This new esoteric form of Buddhism can be traced back to groups of wandering yogi magicians called mahasiddhas.

The question of the origins of early Vajrayana has been taken up by various scholars. David Seyfort Ruegg has suggested that Buddhist tantra employed various elements of a pan-Indian religious substrate which is not specifically Buddhist, Shaiva or Vaishnava.

According to Indologist Alexis Sanderson, various classes of Vajrayana literature developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and Saivism. Sanderson has argued that Buddhist tantras can be shown to have borrowed practices, terms, rituals and more from Shaiva tantras. He argues that Buddhist texts even directly copied various Shaiva tantras, especially the Bhairava Vidyapitha tantras. Ronald M. Davidson meanwhile, argues that Sanderson’s claims for direct influence from Shaiva Vidyapitha texts are problematic because “the chronology of the Vidyapitha tantras is by no means so well established” and that the Shaiva tradition also appropriated non-Hindu deities, texts and traditions. Thus while “there can be no question that the Buddhist tantras were heavily influenced by Kapalika and other Saiva movements” argues Davidson, “the influence was apparently mutual.”

Already during this later era, Buddhism was losing state support in other regions of India, including the lands of the Karkotas, the Pratiharas, the Rashtrakutas, the Pandyas and the Pallavas. This loss of support in favour of Hindu faiths like Vaishnavism and Shaivism is the beginning of the long and complex period of the Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent. The Islamic invasions and conquest of India (10th to 12th century), further damaged and destroyed many Buddhist institutions, leading to its eventual near disappearance from India by the 1200’s.

Read more about Late Indian Buddhism And Tantra here.

Nalanda University

This is the site of Nalanda University, a great centre of Mahāyāna thought.

Vajrabhairava

This is a thangka (a Tibetan Buddhist painting on cotton, silk appliqué, usually depicting a Buddhist) showing Vajrabhairava, circa 1740. Vajrayana adopted deities such as Bhairava, known as Yamantaka in Tibetan Buddhism.

Spread To East And Southeast Asia

The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism to China is most commonly thought to have started in the late 2nd or the 1st century CE, though the literary sources are all open to question. The first documented translation efforts by foreign Buddhist monks in China were in the 2nd century CE, probably as a consequence of the expansion of the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin.

The first documented Buddhist texts translated into Chinese are those of the Parthian An Shigao (148 – 180 CE). The first known Mahāyāna scriptural texts are translations into Chinese by the Kushan monk Lokakṣema in Luoyang, between 178 and 189 CE. From China, Buddhism was introduced to its neighbours Korea (4th century), Japan (6th – 7th centuries), and Vietnam (c. 1st – 2nd centuries).

During the Chinese Tang dynasty (618 – 907), Chinese Esoteric Buddhism was introduced from India and Chan Buddhism (Zen) became a major religion. Chan continued to grow in the Song dynasty (960 – 1279) and it was during this era that it strongly influenced Korean Buddhism and Japanese Buddhism. Pure Land Buddhism also became popular during this period and was often practised together with Chan. It was also during the Song that the entire Chinese canon was printed using over 130,000 wooden printing blocks.

During the Indian period of Esoteric Buddhism (from the 8th century onwards), Buddhism spread from India to Tibet and Mongolia. Johannes Bronkhorst states that the esoteric form was attractive because it allowed both a secluded monastic community as well as the social rites and rituals important to laypersons and to kings for the maintenance of a political state during succession and wars to resist invasion. During the Middle Ages, Buddhism slowly declined in India, while it vanished from Persia and Central Asia as Islam became the state religion.

The Theravada school arrived in Sri Lanka sometime in the 3rd century BCE. Sri Lanka became a base for its later spread to Southeast Asia after the 5th century CE (Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia and coastal Vietnam). Theravada Buddhism was the dominant religion in Burma during the Mon Hanthawaddy Kingdom (1287 – 1552). It also became dominant in the Khmer Empire during the 13th and 14th centuries and in the Thai Sukhothai Kingdom during the reign of Ram Khamhaeng (1237/1247 – 1298).

The Angkor Thom

The Angkor Thom was built in Cambodia by Khmer King Jayavarman VII (circa 1120 – 1218).

Shakyamuni Buddha

Details of Shakyamuni Buddha’s life are mentioned in many Early Buddhist Texts but are inconsistent. His social background and life details are difficult to prove, and the precise dates are uncertain.

Early texts have the Buddha’s family name as Gautama (Pali: Gotama), while some texts give Siddhartha as his surname. He was born in Lumbini, present-day Nepal and grew up in Kapilavastu, a town in the Ganges Plain, near the modern Nepal–India border, and he spent his life in what is now modern Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Some hagiographic legends state that his father was a king named Suddhodana, and his mother was Queen Maya. Scholars such as Richard Gombrich consider this a dubious claim because a combination of evidence suggests he was born in the Shakya community, which was governed by a small oligarchy or republic-like council where there were no ranks but where seniority mattered instead. Some of the stories about Buddha, his life, his teachings, and claims about the society he grew up in may have been invented and interpolated at a later time into the Buddhist texts

According to early texts such as the Pali Ariyapariyesanā-sutta (The discourse on the noble quest) and its Chinese parallel from the Buddhist text Madhyama Āgama, Gautama was moved by the suffering (dukkha) of life and death, and its endless repetition due to rebirth. He thus set out on a quest to find liberation from suffering (also known as nirvana). Early texts and biographies state that Gautama first studied under two teachers of meditation, namely Āḷāra Kālāma (Sanskrit: Arada Kalama) and Uddaka Ramaputta (Sanskrit: Udraka Ramaputra), learning meditation and philosophy, particularly the meditative attainment of the sphere of nothingness from the former, and the sphere of neither perception nor non-perception from the latter.

Finding these teachings to be insufficient to attain his goal, he turned to the practice of severe asceticism, which included a strict fasting regime and various forms of breath control. This too fell short of attaining his goal, and then he turned to the meditative practice of dhyana. He famously sat in meditation under a Ficus religiosa tree ( now called the Bodhi Tree) in the town of Bodh Gaya and attained Awakening (Bodhi).

According to various early texts like the Mahāsaccaka-sutta, and the Samaññaphala Sutta, on awakening, the Buddha gained insight into the workings of karma and his former lives, as well as achieving the ending of the mental defilements (asavas), the ending of suffering, and the end of rebirth in saṃsāra. This event also brought certainty about the Middle Way as the right path of spiritual practice to end suffering. As a fully enlightened Buddha, he attracted followers and founded a Sangha (monastic order). He spent the rest of his life teaching the Dharma he had discovered, and then died, achieving final nirvana, at the age of 80 in Kushinagar, India.

Buddha’s teachings were propagated by his followers, which in the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE became various Buddhist schools of thought, each with its own basket of texts containing different interpretations and authentic teachings of the Buddha; these over time evolved into many traditions of which the more well known and widespread in the modern era are Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism.

Mahajanapadas And Janapadas (Circa 500 BCE)

This map shows ancient kingdoms and cities of India during the time of the Buddha (circa 500 BCE) which is now modern-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan.

Emaciated Buddha Statue

This statue in an Ubosoth in Bangkok and represents the stage of his asceticism.

Worldview

The term Buddhism is an occidental neologism, commonly (and rather roughly according to Donald S. Lopez Jr.) used as a translation for the Dharma of the Buddha, fójiào in Chinese, bukkyō in Japanese, nang pa sangs rgyas pa’i chos in Tibetan, buddhadharma in Sanskrit, buddhaśāsana in Pali.

Read more here.

The Four Noble Truths – Dukkha And Its Ending

The Four Truths express the basic orientation of Buddhism: we crave and cling to impermanent states and things, which is dukkha (translated as incapable of satisfying and painful). This keeps us caught in saṃsāra, the endless cycle of repeated rebirth, dukkha and dying again. But there is a way to liberation from this endless cycle to the state of nirvana, namely following the Noble Eightfold Path.

The truth of dukkha is the basic insight that life in this mundane world, with its clinging and craving to impermanent states and things, is dukkha, and unsatisfactory. We expect happiness from states and things which are impermanent, and therefore cannot attain real happiness.

In Buddhism, dukkha is one of the three marks of existence, along with impermanence and anattā (non-self). Buddhism, like other major Indian religions, asserts that everything is impermanent (anicca), but, unlike them, also asserts that there is no permanent self or soul in living beings (anattā). The ignorance or misperception (avijjā) that anything is permanent or that there is self in any being is considered a wrong understanding, and the primary source of clinging and dukkha.

Dukkha arises when we crave (Pali: taṇhā) and cling to these changing phenomena. The clinging and craving produce karma, which ties us to samsara, the cycle of death and rebirth. Craving includes kama-tanha, craving for sense-pleasures; bhava-tanha, craving to continue the cycle of life and death, including rebirth; and vibhava-tanha, craving to not experience the world and painful feelings.

Dukkha ceases or can be confined when craving and clinging cease or are confined. This also means that no more karma is being produced, and rebirth ends. Cessation is nirvana, blowing out, and peace of mind.

By following the Buddhist path to moksha, liberation, one starts to disengage from craving and clinging to impermanent states and things. The term path is usually taken to mean the Noble Eightfold Path, but other versions of the path can also be found in the Nikayas. The Theravada tradition regards insight into the four truths as liberating in itself.

Read more about Dukkah here.

Read more about The Four Noble Truths here.

Enlightenment Of Buddha

This exhibit is in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA, and is Kushan dynasty, late 2nd to early 3rd century CE, Gandhara.

The Four Noble Truths

This is the Buddha teaching the Four Noble Truths. The image is from a Sanskrit manuscript in Nalanda, Bihar, India.

The Cycle Of Rebirth

Saṃsāra

Saṃsāra means wandering or world, with the connotation of cyclic, circuitous change. It refers to the theory of rebirth and cyclicality of all life, matter, and existence, a fundamental assumption of Buddhism, as with all major Indian religions. Samsara in Buddhism is considered to be dukkha, unsatisfactory and painful, perpetuated by desire and avidya (ignorance), and the resulting karma. Liberation from this cycle of existence, nirvana, has been the foundation and the most important historical justification of Buddhism.

Buddhist texts assert that rebirth can occur in six realms of existence, namely three good realms (heavenly, demi-god, human) and three evil realms (animal, hungry ghosts, hellish). Samsara ends if a person attains nirvana, the blowing out of the afflictions through insight into impermanence and non-self.

The Wheel Of Life

This traditional Tibetan Buddhist Thangka depicts The Wheel Of Life with its six realms.

Rebirth

Rebirth refers to a process whereby beings go through a succession of lifetimes as one of many possible forms of sentient life, each running from conception to death. In Buddhist thought, this rebirth does not involve a soul or any fixed substance. This is because the Buddhist doctrine of anattā (Sanskrit: anātman, no-self doctrine) rejects the concepts of a permanent self or an unchanging, eternal soul found in other religions.

The Buddhist traditions have traditionally disagreed on what it is in a person that is reborn, as well as how quickly the rebirth occurs after death. Some Buddhist traditions assert that the no self doctrine means that there is no enduring self, but there is avacya (inexpressible) personality (pudgala) which migrates from one life to another.

The majority of Buddhist traditions, in contrast, assert that vijñāna (a person’s consciousness) though evolving, exists as a continuum and is the mechanistic basis of what undergoes the rebirth process. The quality of one’s rebirth depends on the merit or demerit gained by one’s karma (i.e. actions), as well as that accrued on one’s behalf by a family member. Buddhism also developed a complex cosmology to explain the various realms or planes of rebirth.

Each individual rebirth takes place within one of five realms according to Theravadins, or six according to other schools (heavenly, demi-gods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hellish).

In East Asian and Tibetan Buddhism, rebirth is not instantaneous, and there is an intermediate state (Tibetan bardo) between one life and the next. The orthodox Theravada position rejects the intermediate state and asserts that the rebirth of a being is immediate. However there are passages in the Samyutta Nikaya of the Pali Canon that seem to lend support to the idea that the Buddha taught about an intermediate stage between one life and the next.

Read more here.

Ramabhar Stupa

The Ramabhar Stupa is in Kushinagar, Uttar Pradesh, India, and is regionally believed to be Buddha’s cremation site containing the Buddha’s ashes, placed by the ancient Malla people (the Malla tribe).

Karma

In Buddhism, karma (from Sanskrit: action, work) drives saṃsāra (the endless cycle of suffering and rebirth for each being). Good, skilful deeds (Pāli: kusala) and bad, unskilful deeds (Pāli: akusala) produce seeds in the unconscious receptacle (ālaya) that mature later either in this life or in a subsequent rebirth. The existence of karma is a core belief in Buddhism, as with all major Indian religions, and it implies neither fatalism nor that everything that happens to a person is caused by karma.

A central aspect of the Buddhist theory of karma is that intent (cetanā) matters and is essential to bring about a consequence or phala (fruit) or vipāka (result). However, good or bad karma accumulates even if there is no physical action, and just having ill or good thoughts creates karmic seeds; thus, actions of body, speech or mind all lead to karmic seeds. In the Buddhist traditions, life aspects affected by the law of karma in past and current births of a being include the form of rebirth, the realm of rebirth, social class, character and major circumstances of a lifetime. It operates like the laws of physics, without external intervention, on every being in all six realms of existence including human beings and gods.

A notable aspect of the karma theory in Buddhism is merit transfer. A person accumulates merit not only through intentions and ethical living but also is able to gain merit from others by exchanging goods and services, such as through dāna (charity to monks or nuns). Further, a person can transfer one’s own good karma to living family members and ancestors.

Read more here.

Liberation

The cessation of the kleshas and the attainment of nirvana (nibbāna), with which the cycle of rebirth ends, has been the primary and the soteriological goal of the Buddhist path for monastic life since the time of the Buddha. The term path is usually taken to mean the Noble Eightfold Path, but other versions of the path can also be found in the Nikayas. In some passages in the Pali Canon, a distinction is being made between right knowledge or insight (sammā-ñāṇa), and right liberation or release (sammā-vimutti), as the means to attain cessation and liberation.

Nirvana literally means blowing out, quenching, and becoming extinguished. In early Buddhist texts, it is the state of restraint and self-control that leads to the blowing out and the ending of the cycles of sufferings associated with rebirths and redeaths. Many later Buddhist texts describe nirvana as identical to anatta with complete emptiness and nothingness.

The nirvana state has been described in Buddhist texts partly in a manner similar to other Indian religions, as the state of complete liberation, enlightenment, highest happiness, bliss, fearlessness, freedom, permanence, non-dependent origination, unfathomable, and indescribable. It has also been described in part differently, as a state of spiritual release marked by emptiness and realisation of non-self.

While Buddhism considers the liberation from saṃsāra as the ultimate spiritual goal, in traditional practice, the primary focus of a vast majority of lay Buddhists has been to seek and accumulate merit through good deeds, donations to monks and various Buddhist rituals in order to gain better rebirths rather than nirvana.

Buddha’s Spiritual Liberation

An aniconic depiction of the Buddha’s spiritual liberation (moksha) or awakening (bodhi), at Sanchi. It shows Mucilinda with his Wives around the Buddha who is not depicted, only symbolized by the Bodhi tree and the empty seat.

Dependent Arising

Pratityasamutpada, also called dependent arising, or dependent origination is the Buddhist theory to explain the nature and relations of being, becoming, existence and ultimate reality. Buddhism asserts that there is nothing independent, except the state of nirvana. All physical and mental states depend on and arise from other pre-existing states, and in turn from them arise other dependent states while they cease.

The dependent arisings have a causal conditioning, and thus Pratityasamutpada is the Buddhist belief that causality is the basis of ontology, not a creator God nor the ontological Vedic concept called universal Self (Brahman) nor any other transcendent creative principle. However, Buddhist thought does not understand causality in terms of Newtonian mechanics; rather it understands it as conditioned arising. In Buddhism, dependent arising refers to conditions created by a plurality of causes that necessarily co-originate a phenomenon within and across lifetimes, such as karma in one life creating conditions that lead to rebirth in one of the realms of existence for another lifetime.

Buddhism applies the theory of dependent arising to explain the origination of endless cycles of dukkha and rebirth, through Twelve Nidānas (or twelve links). It states that because Avidyā (ignorance) exists, Saṃskāras (karmic formations) exist; because Saṃskāras exist therefore Vijñāna (consciousness) exists; and in a similar manner, it links Nāmarūpa (the sentient body), Ṣaḍāyatana (our six senses), Sparśa (sensory stimulation), Vedanā (feeling), Taṇhā (craving), Upādāna (grasping), Bhava (becoming), Jāti (birth), and Jarāmaraṇa (old age, death, sorrow, and pain). By breaking the circuitous links of the Twelve Nidanas, Buddhism asserts that liberation from these endless cycles of rebirth and dukkha can be attained.

Not-Self And Emptiness

A related doctrine in Buddhism is that of anattā (Pali) or anātman (Sanskrit). It is the view that there is no unchanging, permanent self, soul or essence in phenomena. The Buddha and Buddhist philosophers who follow him such as Vasubandhu and Buddhaghosa, generally argue for this view by analyzing the person through the schema of the five aggregates and then attempting to show that none of these five components of personality can be permanent or absolute. This can be seen in Buddhist discourses such as the Anattalakkhana Sutta.

Emptiness or voidness (Skt: Śūnyatā, Pali: Suññatā), is a related concept with many different interpretations throughout the various Buddhisms. In early Buddhism, it was commonly stated that all five aggregates are void (rittaka), hollow (tucchaka), and coreless (asāraka), for example as in the Pheṇapiṇḍūpama Sutta (SN 22:95). Similarly, in Theravada Buddhism, it often simply means that the five aggregates are empty of a Self.

Emptiness is a central concept in Mahāyāna Buddhism, especially in Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka school, and in the Prajñāpāramitā sutras. In Madhyamaka philosophy, emptiness is the view which holds that all phenomena (dharmas) are without any svabhava (literally own-nature or self-nature) and are thus without any underlying essence, and so are empty of being independent. This doctrine sought to refute the heterodox theories of svabhava circulating at the time.

The Three Jewels

All forms of Buddhism revere and take spiritual refuge in the three jewels (triratna): Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

Read more here.

Dharma Wheel And Triratna Symbols From Sanchi Stupa Number 2

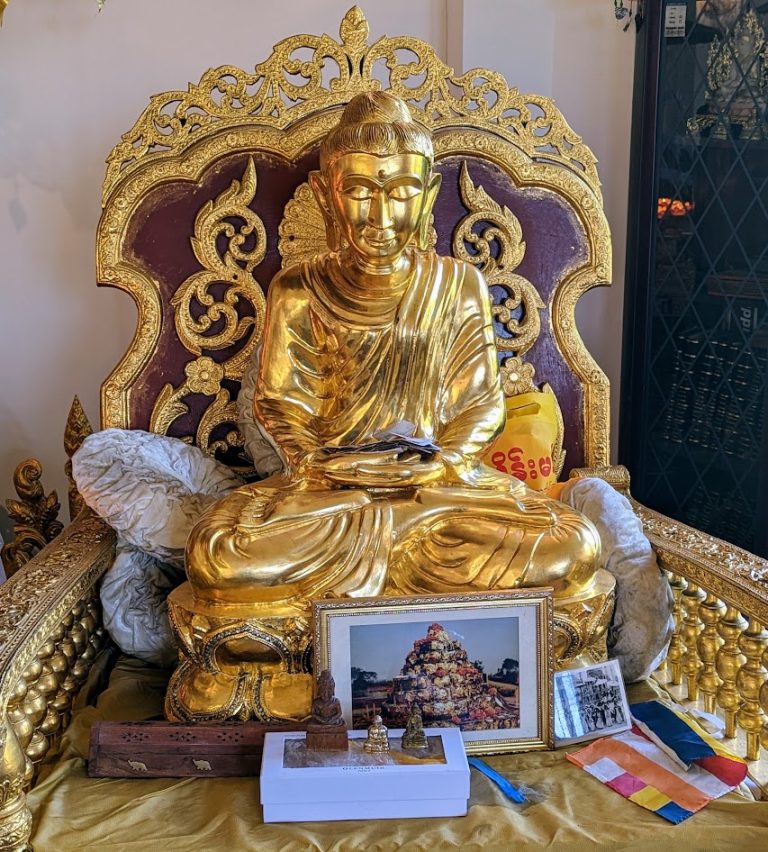

Buddha

While all varieties of Buddhism revere Buddha and Buddhahood, they have different views on what these are. Regardless of their interpretation, the concept of Buddha is central to all forms of Buddhism.

In Theravada Buddhism, a Buddha is someone who has become awake through their own efforts and insight. They have put an end to their cycle of rebirths and have ended all unwholesome mental states which lead to bad action and thus are morally perfected. While subject to the limitations of the human body in certain ways (for example, in the early texts, the Buddha suffers from backaches), a Buddha is said to be deep, immeasurable, hard-to-fathom as is the great ocean, and also has immense psychic powers (abhijñā). Theravada generally sees Gautama Buddha (the historical Buddha Sakyamuni) as the only Buddha of the current era.

Mahāyāna Buddhism meanwhile, has a vastly expanded cosmology, with various Buddhas and other holy beings (aryas) residing in different realms. Mahāyāna texts not only revere numerous Buddhas besides Shakyamuni, such as Amitabha and Vairocana but also see them as transcendental or supramundane (lokuttara) beings. Mahāyāna Buddhism holds that these other Buddhas in other realms can be contacted and are able to benefit beings in this world. In Mahāyāna, a Buddha is a kind of spiritual king, a protector of all creatures with a lifetime that is countless eons long, rather than just a human teacher who has transcended the world after death. Shakyamuni’s life and death on earth is then usually understood as a mere appearance or a manifestation skilfully projected into earthly life by a long-enlightened transcendent being, who is still available to teach the faithful through visionary experiences.

Read more here.

Dharma

The second of the three jewels is Dharma (Pali: Dhamma), which in Buddhism refers to the Buddha’s teaching, which includes all of the main ideas outlined above. While this teaching reflects the true nature of reality, it is not a belief to be clung to, but a pragmatic teaching to be put into practice. It is likened to a raft which is for crossing over (to nirvana) not for holding on to. It also refers to the universal law and cosmic order which that teaching both reveals and relies upon. It is an everlasting principle which applies to all beings and worlds. In that sense it is also the ultimate truth and reality about the universe, it is thus the way that things really are.

Read more here.

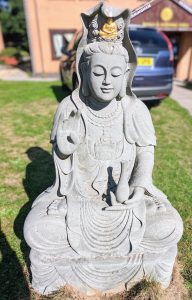

Sangha

The third jewel in which Buddhists take refuge in is the Sangha, which refers to the monastic community of monks and nuns who follow Gautama Buddha’s monastic discipline which was designed to shape the Sangha as an ideal community, with the optimum conditions for spiritual growth. The Sangha consists of those who have chosen to follow the Buddha’s ideal way of life, which is one of celibate monastic renunciation with minimal material possessions (such as an alms bowl and robes).

The Sangha is seen as important because they preserve and pass down Buddha Dharma. As Gethin states “the Sangha lives the teaching, preserves the teaching as Scriptures and teaches the wider community. Without the Sangha, there is no Buddhism. The Sangha also acts as a field of merit for laypersons, allowing them to make spiritual merit or goodness by donating to the Sangha and supporting them. In return, they keep their duty to preserve and spread the Dharma everywhere for the good of the world.

There is also a separate definition of Sangha, referring to those who have attained any stage of awakening, whether or not they are monastics. This sangha is called the āryasaṅgha, the noble Sangha. All forms of Buddhism generally revere these āryas (Pali: ariya, the noble ones or the holy ones) who are spiritually attained beings. Aryas have attained the fruits of the Buddhist path. Becoming an arya is a goal in most forms of Buddhism. The āryasaṅgha includes holy beings such as bodhisattvas, arhats and stream-enterers.

Buddhist Monks And Nuns Praying In The Buddha Tooth Relic Temple Of Singapore

Other Key Mahāyāna Views

Mahāyāna Buddhism also differs from Theravada and the other schools of early Buddhism in promoting several unique doctrines which are contained in Mahāyāna sutras and philosophical treatises.

One of these is the unique interpretation of emptiness and dependent origination found in the Madhyamaka school. Another very influential doctrine for Mahāyāna is the main philosophical view of the Yogācāra school variously, termed Vijñaptimātratā-vāda (the doctrine that there are only ideas or mental impressions) or Vijñānavāda (the doctrine of consciousness). According to Mark Siderits, what classical Yogācāra thinkers like Vasubandhu had in mind is that we are only ever aware of mental images or impressions, which may appear as external objects, but, as he says, “there is actually no such thing outside the mind.” There are several interpretations of this main theory, many scholars see it as a type of Idealism, others as a kind of phenomenology.

Another very influential concept unique to Mahāyāna is that of Buddha-nature (buddhadhātu) or Tathagata-womb (tathāgatagarbha). Buddha-nature is a concept found in some 1st-millennium CE Buddhist texts, such as the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras. According to Paul Williams these Sutras suggest that “all sentient beings contain a Tathagata’ as their ‘essence, core inner nature, Self”. According to Karl Brunnholzl “the earliest Mahayana sutras that are based on and discuss the notion of tathāgatagarbha as the buddha potential that is innate in all sentient beings began to appear in written form in the late second and early third century.” For some, the doctrine seems to conflict with the Buddhist anatta doctrine (non-Self), leading scholars to posit that the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras were written to promote Buddhism to non-Buddhists. This can be seen in texts like the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, which state that Buddha-nature is taught to help those who have fear when they listen to the teaching of anatta. Buddhist texts like the Ratnagotravibhāga clarify that the Self implied in Tathagatagarbha doctrine is actually not self. Various interpretations of the concept have been advanced by Buddhist thinkers throughout the history of Buddhist thought and most attempt to avoid anything like the Hindu Atman doctrine.

These Indian Buddhist ideas, in various synthetic ways, form the basis of subsequent Mahāyāna philosophy in Tibetan Buddhism and East Asian Buddhism.

Blog Posts

Notes And Links

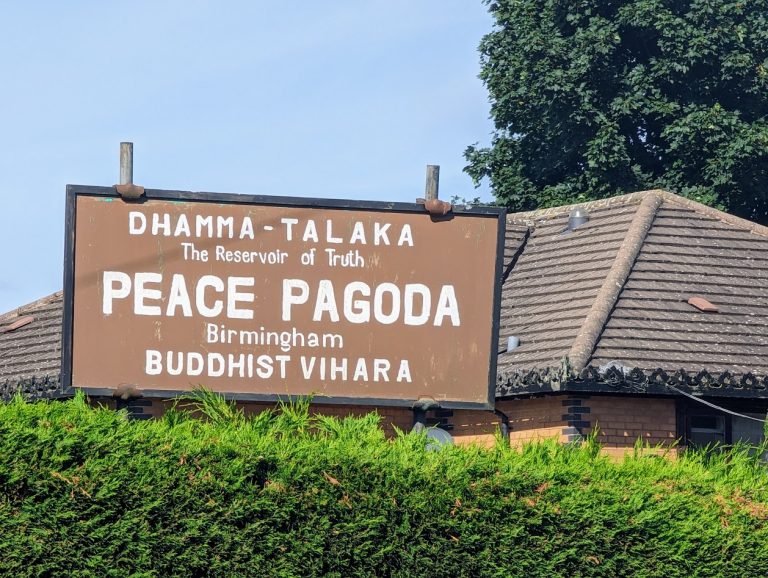

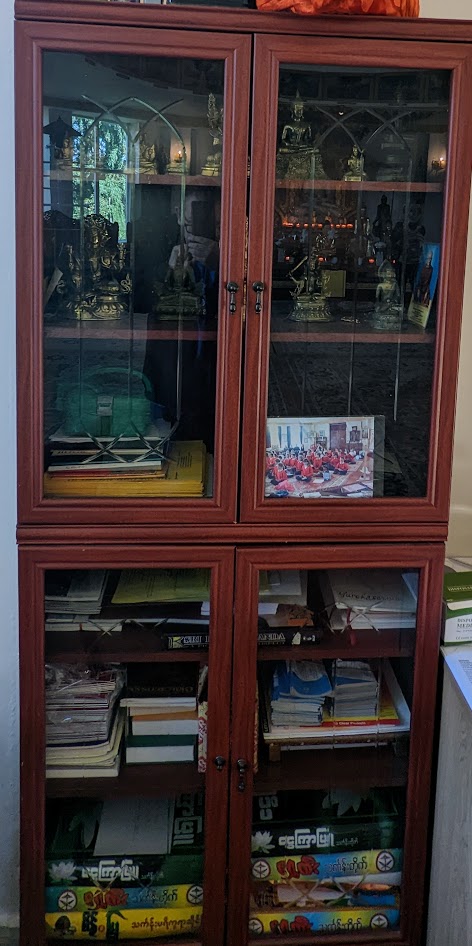

The Birmingham Buddhist Vihara on Facebook.

The image above of the Dharma Wheel is the copyright of Wikipedia user Shazz. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0). You can find more great work from her by clicking here.

The image above of the Vesak Decorations In Sri Lankais the copyright of Wikipedia user Mithila Wijekoon. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of Mahākāśyapa is the copyright of Wikipedia user Daderot. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC0 1.0) and is in the Public Domain.

The image above of Ajanta Caves, Cave 10 is the copyright of an unknown Wikipedia user. It is in the Public Domain.

The image above of Sanchi Stupa Number 3 is the copyright of Wikipedia user Daderot. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of Buddhist Missions is the copyright of Wikipedia user Javierfv1212. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The image above of The Extent Of Buddhism And Trade is the copyright of Wikipedia user World Imaging. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of the Buddhist expansion throughout Asia is the copyright of Wikipedia user Gunawan Kartapranata. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0). You can find more great work from him by clicking here.

The image above of A Buddhist Triad is copyright unknown. It is in the Public Domain. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of Nalanda University is the copyright of Wikipedia user myself. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.5).

The image above of Vajrayana is copyright unknown. It is in the Public Domain.

The image above of The Angkor Thom is the copyright of Wikipedia user Dmitry A. Mottl. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 4.0). You can find more great work from him by clicking here.

The image above of the ancient map is the copyright of Wikipedia user Avantiputra7. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of the Emaciated Buddha Statue is the copyright of Wikipedia user Chainwit. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0). You can find more great work from this photographer by clicking here.

The image above of the Enlightenment Of Buddha is the copyright of Wikipedia user Chainwit. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC0 1.0) and is in the Public Domain.

The image above of The Wheel Of Life is copyright unknown. It is in the Public Domain.

The image above of the Ramabhar Stupa is the copyright of Wikipedia user myself. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.5).

The image above of Buddha’s Spiritual Liberation is the copyright of Wikipedia user Photo Dharma (Anandajoti Bhikkhu). It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 2.0). You can find more great work from him by clicking here.

The image above of Dharma Wheel And Triratna Symbols From Sanchi Stupa Number 2 is the copyright of Kevin Standage. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 2.0). You can find more great work from him by clicking here.

The image above of Buddhist Monks And Nuns Praying In The Buddha Tooth Relic Temple Of Singapore is the copyright of Wikipedia user Basile Morin. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 4.0). You can find more great work from him by clicking here.

Creative Commons – Official website. They offer better sharing, advancing universal access to knowledge and culture, and fostering creativity, innovation, and collaboration.