I don’t practice Buddhism but I have been interested in it for a long time now. It is the only religion I have time for because it truly promotes peace without the need for an imaginary man in the sky and the fear and anything that is not peaceful associated with him.

Contents

Paths To Liberation

The Bodhipakkhiyādhammā are seven lists of qualities or factors that contribute to awakening (bodhi). Each list is a short summary of the Buddhist path, and the seven lists substantially overlap. The best-known list in the West is the Noble Eightfold Path, but a wide variety of paths and models of progress have been used and described in the different Buddhist traditions. However, they generally share basic practices such as sila (ethics), samadhi (meditation, dhyana) and prajña (wisdom), which are known as the three trainings. An important additional practice is a kind and compassionate attitude toward every living being and the world. Devotion is also important in some Buddhist traditions, and in Tibetan traditions, visualisations of deities and mandalas are important. The value of the textual study is regarded differently in the various Buddhist traditions. It is central to Theravada and highly important to Tibetan Buddhism, while the Zen tradition takes an ambiguous stance.

An important guiding principle of Buddhist practice is the Middle Way (madhyamapratipad). It was a part of Buddha’s first sermon, where he presented the Noble Eightfold Path which was a middle way between the extremes of asceticism and a hedonistic sense of pleasures. In Buddhism, states Harvey, the doctrine of dependent arising (conditioned arising, pratītyasamutpāda) to explain rebirth is viewed as the middle way between the doctrines that a being has a permanent soul involved in rebirth (eternalism) and death is final and there is no rebirth (annihilationism).

Read more here.

Paths To Liberation In The Early Texts

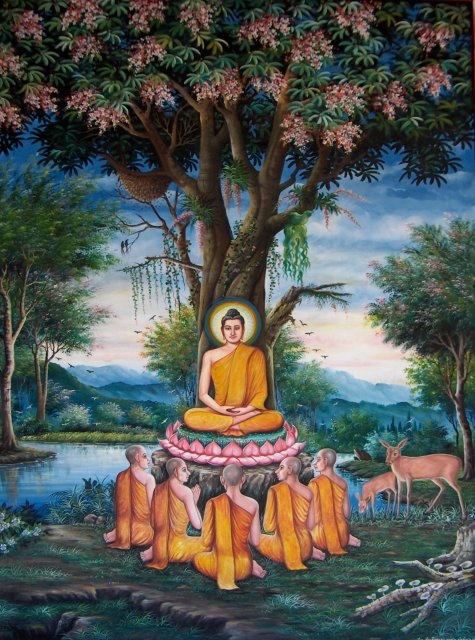

A common presentation style of the path (mārga) to liberation in the Early Buddhist Texts is the graduated talk, in which the Buddha lays out a step-by-step training.

In the early texts, numerous different sequences of the gradual path can be found. One of the most important and widely used presentations among the various Buddhist schools is The Noble Eightfold Path or Eightfold Path of the Noble Ones (Skt. ‘āryāṣṭāṅgamārga’). This can be found in various discourses, most famously in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (The discourse on the turning of the Dharma wheel).

Other suttas such as the Tevijja Sutta, and the Cula-Hatthipadopama-sutta give a different outline of the path, though with many similar elements such as ethics and meditation.

According to Rupert Gethin, the path to awakening is also frequently summarized by another short formula: “abandoning the hindrances, practice of the four establishings of mindfulness, and development of the awakening factors.”

Noble Eightfold Path

The Eightfold Path consists of a set of eight interconnected factors or conditions, that when developed together, lead to the cessation of dukkha. These eight factors are as follows:

Right View (or Right Understanding), Right Intention (or Right Thought), Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

This Eightfold Path is the fourth of the Four Noble Truths and asserts the path to the cessation of dukkha (suffering, pain, unsatisfactoriness). The path teaches that the way of the enlightened ones stopped their craving, clinging and karmic accumulations, and thus ended their endless cycles of rebirth and suffering.

The Noble Eightfold Path is grouped into three basic divisions.

Read more here.

Common Buddhist Practices

Hearing And Learning The Dharma

In various suttas which present the graduated path taught by the Buddha, such as the Samaññaphala Sutta and the Cula-Hatthipadopama Sutta, the first step on the path is hearing the Buddha teach the Dharma. This is then said to lead to the acquiring of confidence or faith in the Buddha’s teachings.

Mahayana Buddhist teachers such as Yin Shun also state that hearing the Dharma and study of the Buddhist discourses is necessary “if one wants to learn and practice the Buddha Dharma.” Likewise, in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, the Stages of the Path (Lamrim) texts generally place the activity of listening to Buddhist teachings as an important early practice.

Sermon In The Deer Park Depicted At Wat Chedi Liam, Near Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand.

Refuge

Traditionally, the first step in most Buddhist schools requires taking of the Three Refuges, also called the Three Jewels (Sanskrit: triratna, Pali: tiratana) as the foundation of one’s religious practice. This practice may have been influenced by the Brahmanical motif of the triple refuge, found in the Rigveda 9.97.47, Rigveda 6.46.9 and Chandogya Upanishad 2.22.3–4. Tibetan Buddhism sometimes adds a fourth refuge, in the lama. The three refuges are believed by Buddhists to be protective and a form of reverence.

The ancient formula which is repeated for taking refuge affirms that “I go to the Buddha as refuge, I go to the Dhamma as refuge, I go to the Sangha as refuge.” Reciting the three refuges, according to Peter Harvey, is considered not as a place to hide, rather a thought that “purifies, uplifts and strengthens the heart”.

Read more here.

Śīla – Buddhist Ethics

Śīla (Sanskrit) or sīla (Pāli) is the concept of moral virtues, which is the second group and an integral part of the Noble Eightfold Path. It generally consists of right speech, right action and right livelihood.

One of the most basic forms of ethics in Buddhism is the taking of precepts. This includes the Five Precepts for laypeople, Eight or Ten Precepts for monastic life, as well as rules of Dhamma (Vinaya or Patimokkha) adopted by a monastery.

Other important elements of Buddhist ethics include giving or charity (dāna), Mettā (Good-Will), Heedfulness (Appamada), self-respect (Hri) and regard for consequences (Apatrapya).

Read more here.

Buddhist Monks Collect Alms In Si Phan Don, Laos.

Giving is a key virtue in Buddhism.

Precepts

Buddhist scriptures explain the five precepts (Pali: pañcasīla; Sanskrit: pañcaśīla) as the minimal standard of Buddhist morality. It is the most important system of morality in Buddhism, together with the monastic rules.

The five precepts are seen as basic training applicable to all Buddhists. They are as follows:

“I undertake the training-precept (sikkha–padam) to abstain from onslaught on breathing beings.” This includes ordering or causing someone else to kill. The Pali suttas also say one should not “approve of others killing” and that one should be “scrupulous, compassionate, trembling for the welfare of all living beings.”

“I undertake the training-precept to abstain from taking what is not given.” According to Harvey, this also covers fraud, cheating, forgery as well as “falsely denying that one is in debt to someone.”

“I undertake the training-precept to abstain from misconduct concerning sense-pleasures.” This generally refers to adultery, as well as rape and incest. It also applies to sex with those who are legally under the protection of a guardian. It is also interpreted in different ways in the varying Buddhist cultures.

“I undertake the training-precept to abstain from false speech.” According to Harvey this includes “any form of lying, deception or exaggeration… even non-verbal deception by gesture or other indication… or misleading statements.” The precept is often also seen as including other forms of wrong speech such as “divisive speech, harsh, abusive, angry words, and even idle chatter.”

“I undertake the training-precept to abstain from alcoholic drink or drugs that are an opportunity for heedlessness.” According to Harvey, intoxication is seen as a way to mask rather than face the sufferings of life. It is seen as damaging to one’s mental clarity, mindfulness and ability to keep the other four precepts.

Undertaking and upholding the five precepts is based on the principle of non-harming (Pāli and Sanskrit: ahiṃsa). The Pali Canon recommends that you compare yourself with others, and on the basis of that, you do not hurt others. Compassion and a belief in karmic retribution form the foundation of the precepts. Undertaking the five precepts is part of regular lay devotional practice, both at home and at the local temple. However, the extent to which people keep them differs per region and time. They are sometimes referred to as the śrāvakayāna precepts in the Mahāyāna tradition, contrasting them with the bodhisattva precepts.

Read more here.

Vinaya

Vinaya is the specific code of conduct for a sangha of monks or nuns. It includes the Patimokkha, a set of 227 offences including 75 rules of decorum for monks, along with penalties for transgression, in the Theravadin tradition. The precise content of the Vinaya Pitaka (scriptures on the Vinaya) differs in different schools and traditions, and different monasteries set their own standards for its implementation. The list of pattimokkha is recited every fortnight in a ritual gathering of all monks. Buddhist text with Vinaya rules for monasteries has been traced in all Buddhist traditions, with the oldest surviving being the ancient Chinese translations.

Monastic communities in the Buddhist tradition cut normal social ties to family and community, and, as Richard F. Gombrich says, “live as islands unto themselves”.

Within a monastic fraternity, a sangha has its own rules. A monk abides by these institutionalised rules, and living life as the Vinaya prescribes it is not merely a means, but very nearly the end in itself. Transgressions by a monk on Sangha Vinaya rules invite enforcement, which can include temporary or permanent expulsion.

Read more here.

A Buddhist Ordination Ceremony.

This is the ordination ceremony at Wat Yannawa in Bangkok. The Vinaya codes regulate the various sangha acts, including ordination.

Restraint And Renunciation

Another important practice taught by the Buddha is the restraint of the senses (indriyasamvara). In the various graduated paths, this is usually presented as a practice which is taught prior to formal sitting meditation, and which supports meditation by weakening sense desires that are a hindrance to meditation. According to scholar and meditation teacher Bhikkhu Anālayo, sense restraint is when one “guards the sense doors in order to prevent sense impressions from leading to desires and discontent.” This is not an avoidance of sense impression, but a kind of mindful attention towards the sense impressions which does not dwell on their main features or signs (nimitta). This is said to prevent harmful influences from entering the mind. This practice is said to give rise to inner peace and happiness which forms a basis for concentration and insight.

A related Buddhist virtue and practice is renunciation or the intent for desirelessness (nekkhamma). Generally, renunciation is the giving up of actions and desires that are seen as unwholesome on the path, such as lust for sensuality and worldly things. Renunciation can be cultivated in different ways. The practice of giving, for example, is one form of cultivating renunciation. Another one is giving up on lay life and becoming a monastic (bhiksu o bhiksuni). Practising celibacy (whether for life as a monk or temporarily) is also a form of renunciation. Many Jataka stories such as focus on how the Buddha practiced renunciation in past lives.

One way of cultivating renunciation taught by the Buddha is the contemplation (anupassana) of the dangers (or negative consequences) of sensual pleasure (kāmānaṃ ādīnava). As part of the graduated discourse, this contemplation is taught after the practice of giving and morality.

Another related practice to renunciation and sense of restraint taught by the Buddha is restraint in eating or moderation with food, which for monks generally means not eating after noon. Devout laypersons also follow this rule during special days of religious observance (uposatha). Observing the Uposatha also includes other practices dealing with renunciation, mainly the eight precepts.

For Buddhist monastics, renunciation can also be trained through several optional ascetic practices called dhutaṅga.

In different Buddhist traditions, other related practices which focus on fasting are followed.

A Buddhist Monk In Khao Luang, Thailand.

Living at the root of a tree (trukkhamulik’anga) is one of the dhutaṅgas, a series of optional ascetic practices for Buddhist monastics.

Mindfulness And Clear Comprehension

The training of the faculty called mindfulness (Pali: sati, Sanskrit: smṛti, literally meaning recollection, remembering) is central in Buddhism. According to Analayo, mindfulness is a full awareness of the present moment which enhances and strengthens memory. The Indian Buddhist philosopher Asanga defined mindfulness thus: “It is non-forgetting by the mind with regard to the object experienced. Its function is non-distraction.” According to Rupert Gethin, sati is also “an awareness of things in relation to things, and hence an awareness of their relative value.”

There are different practices and exercises for training mindfulness in the early discourses, such as the four Satipaṭṭhānas (Sanskrit: smṛtyupasthāna, establishments of mindfulness) and Ānāpānasati (Sanskrit: ānāpānasmṛti, mindfulness of breathing).

A closely related mental faculty, which is often mentioned side by side with mindfulness, is sampajañña (clear comprehension). This faculty is the ability to comprehend what one is doing and what is happening in the mind and whether it is being influenced by unwholesome states or wholesome ones.

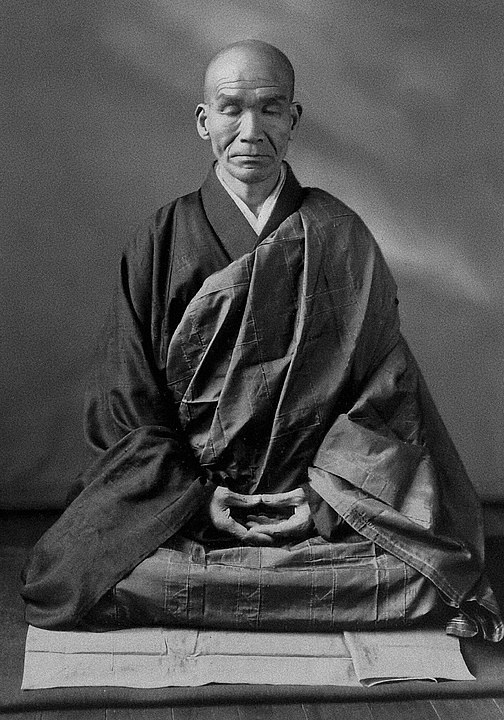

Meditation – Sama–Amādhi And Dhyāna

A wide range of meditation practices has developed in the Buddhist traditions, but meditation primarily refers to the attainment of samādhi and the practice of dhyāna (Pali: jhāna). Samādhi is a calm, undistracted, unified and concentrated state of awareness. It is defined by Asanga as “one-pointedness of mind on the object to be investigated. Its function consists of giving a basis to knowledge (jñāna).” Dhyāna is a state of perfect equanimity and awareness (upekkhā–sati–parisuddhi), reached through focused mental training.

The practice of dhyāna aids in maintaining a calm mind and avoiding disturbance of this calm mind by mindfulness of disturbing thoughts and feelings.

Kodo Sawaki.

He is practising Zazen here (sitting dhyana).

Origins

The earliest evidence of yogis and their meditative tradition, states Karel Werner, is found in the Keśin hymn 10.136 of the Rigveda. While evidence suggests meditation was practised in the centuries preceding the Buddha, the meditative methodologies described in the Buddhist texts are some of the earliest among texts that have survived into the modern era. These methodologies likely incorporate what existed before the Buddha as well as those first developed within Buddhism.

There is no scholarly agreement on the origin and source of the practice of dhyāna. Some scholars, like Johannes Bronkhorst, see the four dhyānas as a Buddhist invention. Alexander Wynne argues that the Buddha learned dhyāna from Brahmanical teachers.

Whatever the case, the Buddha taught meditation with a new focus and interpretation, particularly through the four dhyānas methodology, in which mindfulness is maintained. Further, the focus of meditation and the underlying theory of liberation guiding the meditation has been different in Buddhism. For example, states Bronkhorst, verse 4.4.23 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad with its “become calm, subdued, quiet, patiently enduring, concentrated, one sees soul in oneself” is most probably a meditative state. The Buddhist discussion of meditation is without the concept of the soul and the discussion criticises both the ascetic meditation of Jainism and the real self, soul meditation of Hinduism.

The Formless Attaiments

Often grouped into the jhāna-scheme are four other meditative states, referred to in the early texts as arupa samāpattis (formless attainments). These are also referred to in commentarial literature as immaterial/formless jhānas (arūpajhānas). The first formless attainment is a place or realm of infinite space (ākāsānañcāyatana) without form or colour or shape. The second is termed the realm of infinite consciousness (viññāṇañcāyatana). The third is the realm of nothingness (ākiñcaññāyatana). The fourth is the realm of neither perception nor non-perception. The four rupa–jhānas in Buddhist practice lead to rebirth in successfully better rupa Brahma heavenly realms, while arupa–jhānas lead into arupa heavens.

Meditation And Insight

In the Pali canon, the Buddha outlines two meditative qualities which are mutually supportive: samatha (Pāli; Sanskrit: śamatha; calm) and vipassanā (Sanskrit: vipaśyanā, insight). The Buddha compares these mental qualities to a swift pair of messengers who together help deliver the message of Nibbana (SN 35.245).

The various Buddhist traditions generally see Buddhist meditation as being divided into those two main types. Samatha is also called calming meditation, and focuses on stilling and concentrating the mind i.e. developing samadhi and the four dhyānas. According to Damien Keown, vipassanā meanwhile, focuses on “the generation of penetrating and critical insight (paññā)”.

There are numerous doctrinal positions and disagreements within the different Buddhist traditions regarding these qualities or forms of meditation. For example, in the Pali Four Ways to Arahantship Sutta (AN 4.170), it is said that one can develop calm and then insight, or insight and then calm, or both at the same time. Meanwhile, in Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakośakārikā, vipaśyanā is said to be practised once one has reached samadhi by cultivating the four foundations of mindfulness (smṛtyupasthānas).

Beginning with comments by Belgian Indologist and scholar Louis Étienne Joseph Marie de La Vallée-Poussin, a series of scholars have argued that these two meditation types reflect a tension between two different ancient Buddhist traditions regarding the use of dhyāna, one which focused on insight-based practice and the other which focused purely on dhyāna. However, other scholars such as Analayo and Rupert Gethin have disagreed with this two paths thesis, instead seeing both of these practices as complementary.

Kamakura Daibutsu.

The Kamakura Daibutsu is in Kōtoku-in, Kamakura, Japan.

The Brahma-Vihara

The four immeasurables or four abodes, also called Brahma–viharas, are virtues or directions for meditation in Buddhist traditions, which helps a person be reborn in the heavenly (Brahma) realm. These are traditionally believed to be characteristic of the deity Brahma and the heavenly abode he resides in.

The four Brahma–vihara are:

Loving-kindness (Pāli: mettā, Sanskrit: maitrī) is active goodwill towards all.

Compassion (Pāli and Sanskrit: karuṇā) results from metta; it is identifying the suffering of others as one’s own.

Empathetic joy (Pāli and Sanskrit: muditā): is the feeling of joy because others are happy, even if one did not contribute to it; it is a form of sympathetic joy.

Equanimity (Pāli: upekkhā, Sanskrit: upekṣā): is even-mindedness and serenity, treating everyone impartially.

Read more here.

A Statue Of Buddha In Wat Phra Si Rattana Mahathat, Phitsanulok, Thailand.

Tantra, Visualization And The Subtle Body

Some Buddhist traditions, especially those associated with Tantric Buddhism (also known as Vajrayana and Secret Mantra) use images and symbols of deities and Buddhas in meditation. This is generally done by mentally visualizing a Buddha image (or some other mental image, like a symbol, a mandala, a syllable, etc.), and using that image to cultivate calm and insight. One may also visualize and identify oneself with the imagined deity. While visualization practices have been particularly popular in Vajrayana, they may also be found in Mahayana and Theravada traditions.

In Tibetan Buddhism, unique tantric techniques which include visualization (but also mantra recitation, mandalas, and other elements) are considered to be much more effective than non-tantric meditations and they are one of the most popular meditation methods. The methods of Unsurpassable Yoga Tantra, (anuttarayogatantra) are in turn seen as the highest and most advanced. Anuttarayoga practice is divided into two stages, the Generation Stage and the Completion Stage. In the Generation Stage, one meditates on emptiness and visualizes oneself as a deity as well as visualizing its mandala. The focus is on developing a clear appearance and divine pride (the understanding that oneself and the deity are one). This method is also known as deity yoga (devata yoga). There are numerous meditation deities (yidam) used, each with a mandala, a circular symbolic map used in meditation.

An 18th Century Mongolian Miniature Depicting The Generation Of The Vairocana Mandala.

Insight And Knowledge

Prajñā (Sanskrit) or paññā (Pāli) is wisdom or knowledge of the true nature of existence. Another term which is associated with prajñā and sometimes is equivalent to it is vipassanā (Pāli) or vipaśyanā (Sanskrit), which is often translated as insight. In Buddhist texts, the faculty of insight is often said to be cultivated through the four establishments of mindfulness. In the early texts, Paññā is included as one of the five faculties (indriya) which are commonly listed as important spiritual elements to be cultivated (see for example AN I 16). Paññā along with samadhi, is also listed as one of the trainings in the higher states of mind (adhicittasikkha).

The Buddhist tradition regards ignorance (avidyā), a fundamental ignorance, misunderstanding or misperception of the nature of reality, as one of the basic causes of dukkha and samsara. Overcoming this ignorance is part of the path to awakening. This overcoming includes the contemplation of impermanence and the non-self nature of reality, and this develops dispassion for the objects of clinging, and liberates a being from dukkha and saṃsāra. Prajñā is important in all Buddhist traditions. It is variously described as wisdom regarding the impermanent and not-self nature of dharmas (phenomena), the functioning of karma and rebirth, and knowledge of dependent origination. Likewise, vipaśyanā is described in a similar way, such as in the Paṭisambhidāmagga, where it is said to be the contemplation of things as impermanent, unsatisfactory and not self.

The Yogic Practice Of Tummo.

The image above shows a section of the Northern wall mural at the Lukhang Temple depicting tummo, the three channels (nadis) and phowa.

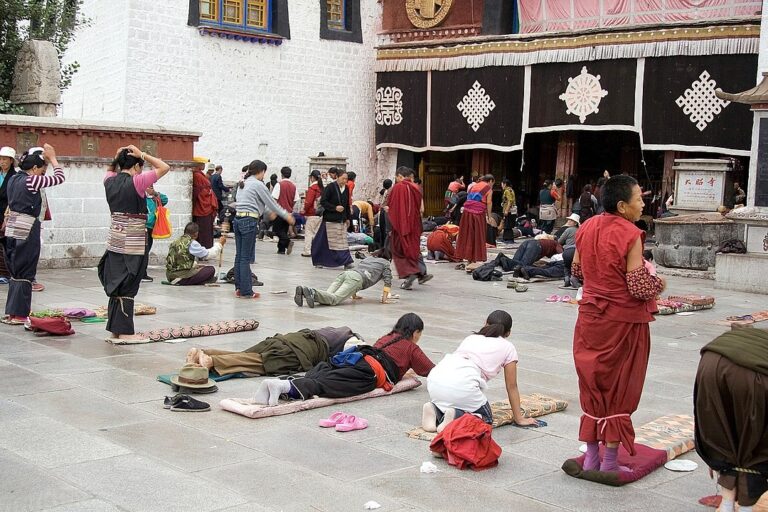

Devotion

According to Peter Harvey most forms of Buddhism “consider saddhā (Skt śraddhā), trustful confidence or faith, as a quality which must be balanced by wisdom, and as a preparation for, or accompaniment of, meditation.”. Because of this devotion (Skt. bhakti; Pali: Bhatti) is an important part of the practice of most Buddhists. Devotional practices include ritual prayer, prostration, offerings, pilgrimage, and chanting. Buddhist devotion is usually focused on some object, image or location that is seen as holy or spiritually influential. Examples of objects of devotion include paintings or statues of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, stupas, and bodhi trees. Public group chanting for devotional and ceremonial is common to all Buddhist traditions and goes back to ancient India where chanting aided in the memorization of the orally transmitted teachings. Rosaries called Malas are used in all Buddhist traditions to count repeated chanting of common formulas or mantras. Chanting is thus a type of devotional group meditation which leads to tranquillity and communicates Buddhist teachings.

Read more here.

Tibetan Buddhist Prostration Practice At Jokhang, Tibet.

Vegetarianism And Animal Ethics

Based on the Indian principle of ahimsa (non-harming), the Buddha’s ethics strongly condemn the harming of all sentient beings, including all animals. He thus condemned the animal sacrifice of the Brahmins as well as hunting, and killing animals for food. However, early Buddhist texts depict the Buddha as allowing monastics to eat meat. This seems to be because monastics begged for their food and thus were supposed to accept whatever food was offered to them. Norm Phelps states that this was tempered by the rule that meat had to be “three times clean” which meant that “they had not seen, had not heard, and had no reason to suspect that the animal had been killed so that the meat could be given to them”. Also, while the Buddha did not explicitly promote vegetarianism in his discourses, he did state that gaining one’s livelihood from the meat trade was unethical. In contrast to this, various Mahayana sutras and texts like the Mahaparinirvana sutra, Surangama sutra and the Lankavatara sutra state that the Buddha promoted vegetarianism out of compassion. Indian Mahayana thinkers like Shantideva promoted the avoidance of meat. Throughout history, the issue of whether Buddhists should be vegetarian has remained a much-debated topic and there is a variety of opinions on this issue among modern Buddhists.

Read more here.

A Vegetarian Meal At A Buddhist Temple.

East Asian Buddhism tends to promote vegetarianism.

Blog Posts

Notes And Links

The Birmingham Buddhist Vihara on Facebook.

The image above of Sermon In The Deer Park Depicted At Wat Chedi Liam, Near Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand is copyright unknown. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of Buddhist Monks Collect Alms In Si Phan Don, Laos is the copyright of Wikipedia user Basile Morin. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 4.0). You can find more great work from him by clicking here.

The image above of A Buddhist Ordination Ceremony is copyright of Wikipedia user Photogoddle. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 4.0).

The image above of A Buddhist Monk In Khao Luang, Thailand is copyright of Wikipedia user Tevaprapas. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 3.0). You can find more great work from him/her by clicking here.

The image above of Kodo Sawaki is in the Public Domain.

The image above of The Kamakura Daibutsu is in the Public Domain.

The image above of A Statue Of Buddha In Wat Phra Si Rattana Mahathat, Phitsanulok, Thailand is copyright of Wikipedia user JJ Harrison. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 3.0). You can find more great work from him by clicking here.

The image above of An 18th Century Mongolian Miniature Depicting The Generation Of The Vairocana Mandala is in the Public Domain.

The image above of The Yogic Practice Of Tummo is in the Public Domain.

The image above of Tibetan Buddhist Prostration Practice At Jokhang, Tibet is the copyright of Wikipedia user Luca Galuzzi. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.5). You can find more great work from him by clicking here.

The image above of A Vegetarian Meal At A Buddhist Temple is copyright of Andrea Schaffer. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 2.0). You can find more great work from her by clicking here.

The image above of A Depiction Of The Supposed First Buddhist Council At Rajgir is copyright of Wikipedia user Anandajoti. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 2.0).

Creative Commons – Official website. They offer better sharing, advancing universal access to knowledge and culture, and fostering creativity, innovation, and collaboration.