I don’t practice Buddhism but I have been interested in it for a long time now. It is the only religion I have time for because it truly promotes peace without the need for an imaginary man in the sky and the fear and anything that is not peaceful associated with him.

Contents

Buddhist Texts

Buddhism, like all Indian religions, was initially an oral tradition in ancient times. The Buddha’s words, the early doctrines, concepts, and their traditional interpretations were orally transmitted from one generation to the next. The earliest oral texts were transmitted in Middle Indo-Aryan languages called Prakrits, such as Pali, through the use of communal recitation and other mnemonic techniques.

The first Buddhist canonical texts were likely written down in Sri Lanka, about 400 years after the Buddha died. The texts were part of the Tripitakas, and many versions appeared thereafter claiming to be the words of the Buddha. Scholarly Buddhist commentary texts, with named authors, appeared in India, around the 2nd century CE. These texts were written in Pali or Sanskrit, sometimes regional languages, such as palm-leaf manuscripts, birch bark, painted scrolls, carved into temple walls, and later on paper.

Unlike what the Bible is to Christianity and the Quran is to Islam, like all major ancient Indian religions, there is no consensus among the different Buddhist traditions as to what constitutes the scriptures or a common canon in Buddhism. The general belief among Buddhists is that the canonical corpus is vast. This corpus includes the ancient Sutras organised into Nikayas or Agamas, itself part of three baskets of texts called the Tripitakas. Each Buddhist tradition has its own collection of texts, much of which is a translation of ancient Pali and Sanskrit Buddhist texts of India. The Chinese Buddhist canon, for example, includes 2184 texts in 55 volumes, while the Tibetan canon comprises 1108 texts (all claimed to have been spoken by the Buddha) and another 3461 texts composed by Indian scholars revered in the Tibetan tradition. The Buddhist textual history is vast; over 40,000 manuscripts (mostly Buddhist, some non-Buddhist) were discovered in 1900 in the Dunhuang Chinese cave alone.

Read more here.

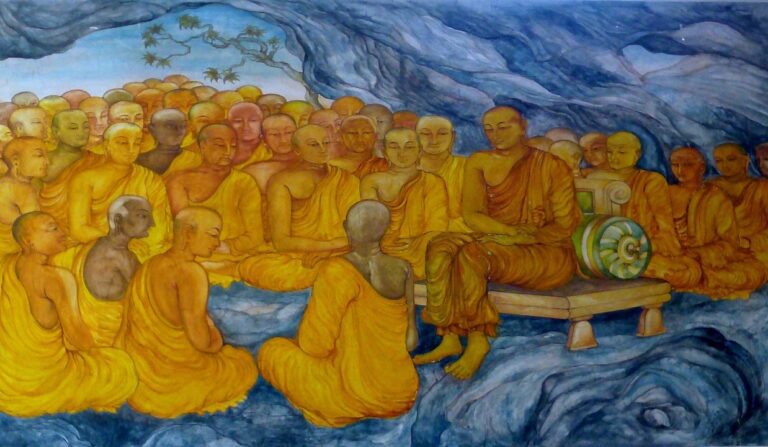

A Depiction Of The Supposed First Buddhist Council At Rajgir.

The image above shows the first Council at Rajagaha, at the Nava Jetavana, and the current Rajgir (around the 5th century BC).

The communal recitation was one of the original ways of transmitting and preserving Early Buddhist texts.

Early Buddhist Texts

Read more here.

The Early Buddhist Texts refer to the literature which is considered by modern scholars to be the earliest Buddhist material. The first four Pali Nikayas and the corresponding Chinese Āgamas are generally considered to be among the earliest material. Apart from these, there are also fragmentary collections of EBT materials in other languages such as Sanskrit, Khotanese, Tibetan and Gāndhārī. The modern study of early Buddhism often relies on comparative scholarship using these various early Buddhist sources to identify parallel texts and common doctrinal content. One feature of these early texts is literary structures which reflect oral transmission, such as widespread repetition.

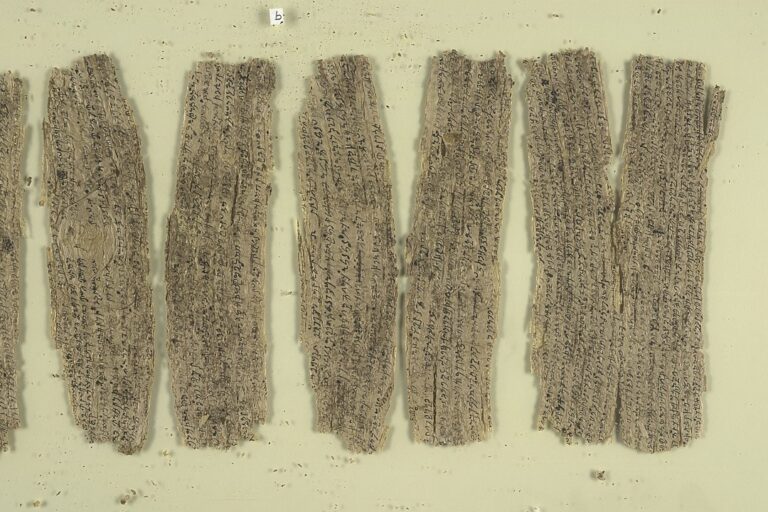

Gandhara Birchbark Scroll Fragments.

This manuscript from the British Library Collection (c. 1st century) is written on birchbark and is part of a group of early manuscripts from Gandhara (modern East Afghanistan).

The Tripitakas

After the development of the different early Buddhist schools, these schools began to develop their own textual collections, which were termed Tripiṭakas (Triple Baskets).

Many early Tripiṭakas, like the Pāli Tipitaka, was divided into three sections: Vinaya Pitaka (focuses on monastic rule), Sutta Pitaka (Buddhist discourses) and Abhidhamma Pitaka, which contain expositions and commentaries on the doctrine. The Pāli Tipitaka (also known as the Pali Canon) of the Theravada School constitutes the only complete collection of Buddhist texts in an Indic language which has survived until today. However, many Sutras, Vinayas and Abhidharma work from other schools survive in Chinese translation, as part of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. According to some sources, some early schools of Buddhism had five or seven pitakas.

Mahāyāna Texts

The Mahāyāna sūtras are a very broad genre of Buddhist scriptures that the Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition holds are original teachings of the Buddha. Modern historians generally hold that the first of these texts were composed probably around the 1st century BCE or 1st century CE. In Mahāyāna, these texts are generally given greater authority than the early Āgamas and Abhidharma literature, which are called Śrāvakayāna or Hinayana to distinguish them from Mahāyāna sūtras. Mahāyāna traditions mainly see these different classes of texts as being designed for different types of persons, with different levels of spiritual understanding. The Mahāyāna sūtras are alleged to be seen as being for those of greater capacity. Mahāyāna also has a very large literature of philosophical and exegetical texts. These are often called śāstra (treatises) or vrittis (commentaries). Some of this literature was also written in verse form (karikās), the most famous of which is the Mūlamadhyamika-karikā (Root Verses on the Middle Way) by Nagarjuna, the foundational text of the Madhyamika school.

Read more here.

Tantric Texts

During the Gupta Empire, a new class of Buddhist sacred literature began to develop, which are called the Tantras. By the 8th century, the tantric tradition was very influential in India and beyond. Besides drawing on a Mahāyāna Buddhist framework, these texts also borrowed deities and material from other Indian religious traditions, such as the Śaiva and Pancharatra traditions, local god/goddess cults, and local spirit worship (such as yaksha or nāga spirits).

Some features of these texts include the widespread use of mantras, meditation on the subtle body, worship of fierce deities, and antinomian and transgressive practices such as ingesting alcohol and performing sexual rituals.

Read more here.

The Tripiṭaka Koreana In South Korea.

This edition of the Chinese Buddhist canon is stored at Haeinsa (Temple of Reflection on a Smooth Sea). It is one of the foremost Chogye Buddhist temples in South Korea. The whole of the Buddhist Scriptures is carved onto 81,258 wooden printing blocks, which Haeinsa has housed since 1398.

Schools And Traditions

Buddhists generally classify themselves as either Theravāda or Mahāyāna. This classification is also used by some scholars and is the one ordinarily used in the English language. An alternative scheme used by some scholars divides Buddhism into the following three traditions or geographical or cultural areas: Theravāda (or Southern Buddhism, South Asian Buddhism), East Asian Buddhism (or just Eastern Buddhism) and Indo-Tibetan Buddhism (or Northern Buddhism).

Some scholars use other schemes and Buddhists themselves have a variety of other schemes. Hinayana (literally lesser or inferior vehicle) is sometimes used by Mahāyāna followers to name the family of early philosophical schools and traditions from which contemporary Theravāda emerged, but as the Hinayana term is considered derogatory, a variety of other terms are used instead, including Śrāvakayāna, Nikaya Buddhism, early Buddhist schools, sectarian Buddhism and conservative Buddhism.

Not all traditions of Buddhism share the same philosophical outlook or treat the same concepts as central. Each tradition, however, does have its own core concepts, and some comparisons can be drawn between them:

Both Theravāda and Mahāyāna accept and revere the Buddha Sakyamuni as the founder, Mahāyāna also reveres numerous other Buddhas, such as Amitabha or Vairocana as well as many other bodhisattvas not revered in Theravāda.

Both accept the Middle Way, Dependent origination, the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, the Three Jewels, the Three marks of existence and the Bodhipakṣadharmas (aids to awakening).

Mahāyāna focuses mainly on the bodhisattva path to Buddhahood which it sees as universal and to be practised by all persons, while Theravāda does not focus on teaching this path and teaches the attainment of arhatship as a worthy goal to strive towards. The bodhisattva path is not denied in Theravāda, it is generally seen as a long and difficult path suitable for only a few. Thus the Bodhisattva path is normative in Mahāyāna, while it is an optional path for a heroic few in Theravāda.

Mahāyāna sees the arhat’s nirvana as being imperfect and inferior or preliminary to full Buddhahood. It sees arhatship as selfish since bodhisattvas vow to save all beings while arhats save only themselves. Theravāda meanwhile does not accept that the arhat’s nirvana is an inferior or preliminary attainment, nor that it is a selfish deed to attain arhatship since not only are arhats described as compassionate but they have destroyed the root of greed, the sense of I am.

Mahāyāna accepts the authority of the many Mahāyāna sutras along with the other Nikaya texts like the Agamas and the Pali canon (though it sees Mahāyāna texts as primary), while Theravāda does not accept that the Mahāyāna sutras are buddhavacana (word of the Buddha) at all.

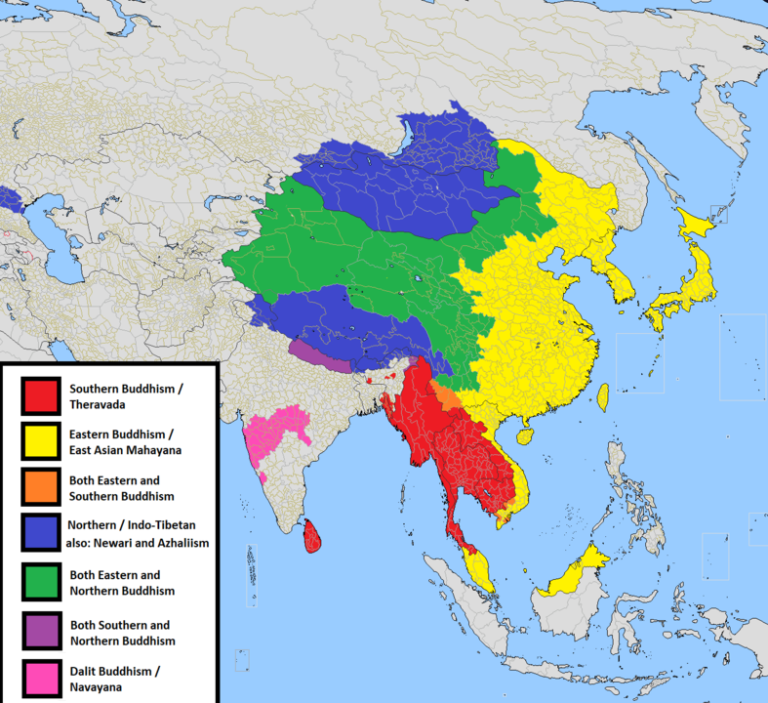

Distribution Of Major Buddhist Traditions.

This map of the main modern Buddhist sects is sourced from Rupert Gethin’s The Foundations of Buddhism.

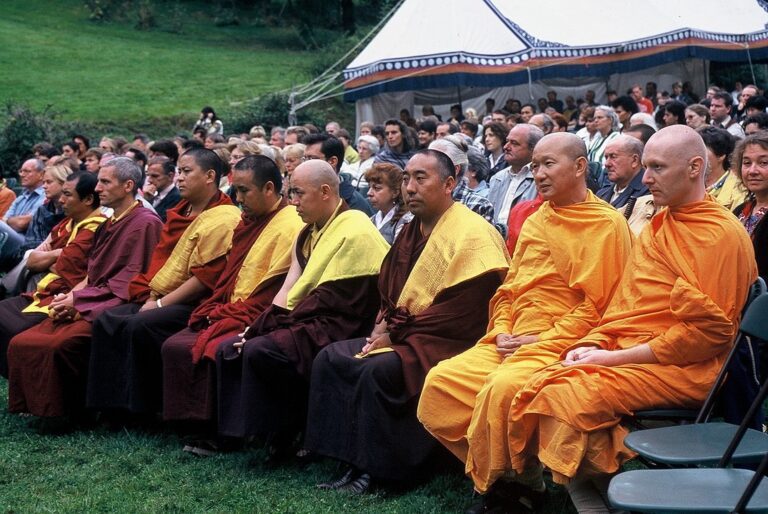

Buddhists In Belgium.

This is a meeting of Belgian Buddhist representatives at the Yeunten Ling Tibetan Institute, Huy on the 3rd of September, 1997.

Monasteries And Temples

Buddhist institutions are often housed and centred around monasteries (Sanskrit:viharas) and temples. Buddhist monastics originally followed a life of wandering, never staying in one place for long. During the three-month rainy season (vassa) they would gather together in one place for a period of intense practice and then depart again. Some of the earliest Buddhist monasteries were at groves (vanas) or woods (araññas), such as Jetavana and Sarnath’s Deer Park. There originally seem to have been two main types of monasteries, monastic settlements (sangharamas) were built and supported by donors, and woodland camps (avasas) were set up by monks. Whatever structures were built in these locales were made out of wood and were sometimes temporary structures built for the rainy season. Over time, the wandering community slowly adopted more settled cenobitic forms of monasticism.

There are many different forms of Buddhist structures. Classic Indian Buddhist institutions mainly made use of the following structures: monasteries, rock-hewn cave complexes (such as the Ajanta Caves), stupas (funerary mounds which contained relics), and temples such as the Mahabodhi Temple. In Southeast Asia, the most widespread institutions are centred on wats. East Asian Buddhist institutions also use various structures including monastic halls, temples, lecture halls, bell towers and pagodas. In Japanese Buddhist temples, these different structures are usually grouped together in an area termed the garan. In Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Buddhist institutions are generally housed in gompas. They include monastic quarters, stupas and prayer halls with Buddha images. In the modern era, the Buddhist meditation centre, which is mostly used by laypersons and often also staffed by them, has also become widespread.

Read more here.

The Mahabodhi Temple, Bodh Gaya, India.

Boudha Stupa In Kathmandu, Nepal.

Buddhism In The Modern Era

Colonial Era

Buddhism has faced various challenges and changes during the colonisation of Buddhist states by Christian countries and its persecution under modern states. Like other religions, the findings of modern science have challenged its basic premises. One response to some of these challenges has come to be called Buddhist modernism. Early Buddhist modernist figures such as the American convert Henry Olcott (1832 – 1907) and Anagarika Dharmapala (1864 – 1933) reinterpreted and promoted Buddhism as a scientific and rational religion which they saw as compatible with modern science.

East Asian Buddhism meanwhile suffered under various wars which ravaged China during the modern era, such as the Taiping Rebellion and World War II (which also affected Korean Buddhism). During the Republican period (1912 – 49), a new movement called Humanistic Buddhism was developed by figures such as Taixu (1899 – 1947), and though Buddhist institutions were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966 – 76), there has been a revival of the religion in China after 1977. Japanese Buddhism also went through a period of modernisation during the Meiji period. In Central Asia meanwhile, the arrival of Communist repression in Tibet (1966 – 1980) and Mongolia (between 1924 and 1990) had a strong negative impact on Buddhist institutions, though the situation has improved somewhat since the 80’s and 90’s.

A Buryat Buddhist monk in Siberia.

Buddhism In The West

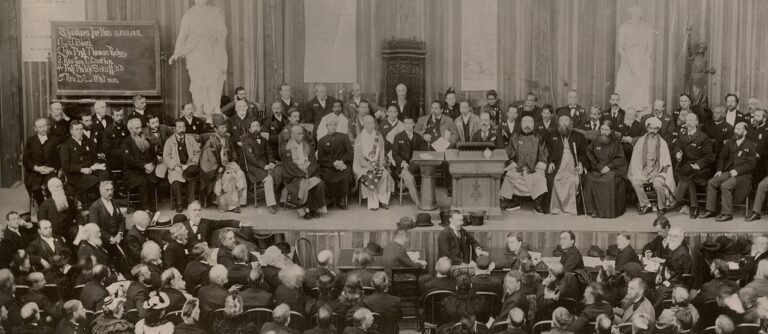

While there were some encounters of Western travellers or missionaries such as St. Francis Xavier and Ippolito Desideri with Buddhist cultures, it was not until the 19th century that Buddhism began to be studied by Western scholars. It was the work of pioneering scholars such as Eugène Burnouf, Max Müller, Hermann Oldenberg and Thomas William Rhys Davids that paved the way for modern Buddhist studies in the West. The English words such as Buddhism, Boudhist, Bauddhist and Buddhist were coined in the early 19th century in the West, while in 1881, Rhys Davids founded the Pali Text Society, an influential Western resource of Buddhist literature in the Pali language and one of the earliest publisher of a journal on Buddhist studies. It was also during the 19th century that Asian Buddhist immigrants (mainly from China and Japan) began to arrive in Western countries such as the United States and Canada, bringing with them their Buddhist religion. This period also saw the first Westerners to formally convert to Buddhism, such as Helena Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott. An important event in the introduction of Buddhism to the West was the 1893 World Parliament of Religions, which for the first time saw well-publicized speeches by major Buddhist leaders alongside other religious leaders.

The 20th century saw a prolific growth of new Buddhist institutions in Western countries, including the Buddhist Society, London (1924), Das Buddhistische Haus (1924) and Datsan Gunzechoinei in St Petersburg. The publication and translations of Buddhist literature in Western languages thereafter accelerated. After the second world war, further immigration from Asia, globalisation, the secularisation of Western culture as well a renewed interest in Buddhism among the ’60s counter-culture led to further growth in Buddhist institutions. Influential figures on post-war Western Buddhism include Shunryu Suzuki, Jack Kerouac, Alan Watts, Thích Nhất Hạnh, and the 14th Dalai Lama. While Buddhist institutions have grown, some of the central premises of Buddhism such as the cycles of rebirth and the Four Noble Truths have been problematic in the West. In contrast, states Christopher Gowans, for “most ordinary [Asian] Buddhists, today as well as in the past, their basic moral orientation is governed by belief in karma and rebirth”. Most Asian Buddhist laypersons, states Kevin Trainor, have historically pursued Buddhist rituals and practices seeking better rebirth, not nirvana or freedom from rebirth.

The 1893 World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, Illinois, United States.

Interior of the Thai Buddhist wat in Nukari, Nurmijärvi, Finland.

Neo-Buddhism Movements

A number of modern movements in Buddhism emerged during the second half of the 20th century. These new forms of Buddhism are diverse and significantly depart from traditional beliefs and practices.

In India, B.R. Ambedkar launched the Navayana tradition (literally, “new vehicle”). Ambedkar’s Buddhism rejects the foundational doctrines and historic practices of traditional Theravada and Mahayana traditions, such as monk lifestyle after renunciation, karma, rebirth, samsara, meditation, nirvana, Four Noble Truths and others. Ambedkar’s Navayana Buddhism considers these as superstitions and re-interprets the original Buddha as someone who taught about class struggle and social equality. Ambedkar urged low-caste Indian Dalits to convert to his Marxism-inspired reinterpretation called Navayana Buddhism, also known as Bhimayana Buddhism. Ambedkar’s effort led to the expansion of Navayana Buddhism in India.

The Thai King Mongkut (r. 1851 – 68), and his son Chulalongkorn (r. 1868 – 1910), were responsible for modern reforms of Thai Buddhism. Modern Buddhist movements include Secular Buddhism in many countries, Won Buddhism in Korea, the Dhammakaya movement in Thailand and several Japanese organisations, such as Shinnyo-en, Risshō Kōsei Kai or Soka Gakkai.

Some of these movements have brought internal disputes and strife within regional Buddhist communities. For example, the Dhammakaya movement in Thailand teaches a true self doctrine, which traditional Theravada monks consider as heretically denying the fundamental anatta (not-self) doctrine of Buddhism.

Read more here.

Cultural Influence

Buddhism has had a profound influence on various cultures, especially in Asia. Buddhist philosophy, Buddhist art, Buddhist architecture, Buddhist cuisine and Buddhist festivals continue to be influential elements of the modern Culture of Asia, especially in East Asia and the Sinosphere as well as in Southeast Asia and the Indosphere. According to Litian Fang, Buddhism has “permeated a wide range of fields, such as politics, ethics, philosophy, literature, art and customs,” in these Asian regions. Buddhist teachings influenced the development of modern Hinduism as well as other Asian religions like Taoism and Confucianism. Buddhist philosophers like Dignaga and Dharmakirti were very influential in the development of Indian logic and epistemology. Buddhist educational institutions like Nalanda and Vikramashila preserved various disciplines of classical Indian knowledge such as grammar, astronomy/astrology and medicine and taught foreign students from Asia.

In the Western world, Buddhism has had a strong influence on modern New Age spirituality and other alternative spiritualities. This began with its influence on 20th-century Theosophists such as Helena Blavatsky, which were some of the first Westerners to take Buddhism seriously as a spiritual tradition. More recently, Buddhist meditation practices have influenced the development of modern psychology, particularly the practice of Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and other similar mindfulness-based modalities. The influence of Buddhism on psychology can also be seen in certain forms of modern psychoanalysis.

Shamanism is a widespread practice in some Buddhist societies. Buddhist monasteries have long existed alongside local shamanic traditions. Lacking an institutional orthodoxy, Buddhists adapted to the local cultures, blending their own traditions with pre-existing shamanic culture. Research into Himalayan religion has shown that Buddhist and shamanic traditions overlap in many respects: the worship of localized deities, healing rituals and exorcisms. The shamanic Gurung people have adopted some of the Buddhist beliefs such as rebirth but maintain the shamanic rites of guiding the soul after death.

Read more here.

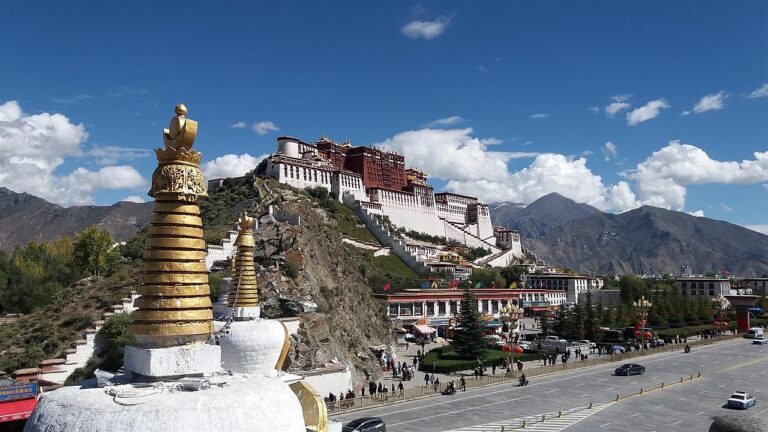

Lhasa’s Potala Palace In Tibet.

The Palace, pictured here in 2019, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Demographics

Buddhism is practised by an estimated 488 million, 495 million, or 535 million people as of the 2010’s, representing 7% to 8% of the world’s total population. China is the country with the largest population of Buddhists, approximately 244 million or 18% of its total population. They are mostly followers of Chinese schools of Mahayana, making this the largest body of Buddhist traditions. Mahayana also practised in broader East Asia, is followed by over half of world Buddhists.

Buddhism is the dominant religion in Bhutan, Myanmar, Cambodia, Hong Kong, Japan, Tibet, Laos, Macau, Mongolia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam. Large Buddhist populations live in Mainland China, Taiwan, North Korea, Nepal and South Korea. In Russia, Buddhists form majority in Tuva (52%) and Kalmykia (53%). Buryatia (20%) and Zabaykalsky Krai (15%) also have significant Buddhist populations.

Buddhism is also growing by conversion. In New Zealand, about 25 to 35% of the total Buddhists are converts to Buddhism. Buddhism has also spread to the Nordic countries; for example, the Burmese Buddhists founded in the city of Kuopio in North Savonia the first Buddhist monastery of Finland, named the Buddha Dhamma Ramsi monastery.

Read more here.

Blog Posts

Notes And Links

The Birmingham Buddhist Vihara on Facebook.

The image above of A Depiction Of The Supposed First Buddhist Council At Rajgir is copyright of Wikipedia user Anandajoti. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 2.0).

The image above of Gandhara Birchbark Scroll Fragments is in the Public Domain.

The image above of The Tripiṭaka Koreana In South Korea is copyright of Lauren Heckler. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 2.0). You can find more great work from her by clicking here.

The image above of Distribution Of Major Buddhist Traditions is copyright of Wikipedia user Javierfv1212. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of Buddhists In Belgium is copyright of Wikipedia user Phra Nicholas Thanissaro and is in the Public Domain.

The image above of The Mahabodhi Temple, Bodh Gaya, India is copyright of Wikipedia user Cacahuate. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.5).

The image above of Boudha Stupa In Kathmandu, Nepal is copyright of Wikipedia user Nabin K. Sapkota. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The image above of Buryat Buddhist monk in Siberia is copyright of Wikipedia user Аркадий Зарубин. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The image above of The 1893 World Parliament Of Religions is in the Public Domain.

The image above of Interior of the Thai Buddhist wat in Nukari is copyright of Wikipedia user CartingCarl. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The image above of Lhasa’s Potala Palace In Tibet is copyright of Wikipedia user 钉钉. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Creative Commons – Official website. They offer better sharing, advancing universal access to knowledge and culture, and fostering creativity, innovation, and collaboration.