Please note this page has been slightly edited for website purposes from the original booklet and is presented to you with kind permission from Jeffery.

The original booklet is available to download and as an e-book at the bottom of this page in the Links section and will appear slightly different to what you see here but the content is the same.

About The Allcott’s

In Jeffrey’s own words:

“The Allcott family were typical of the many thousands of people who once turned to the canals for their livelihood during the middle and latter part of the Victorian era. Times were especially hard for the poorest people in society, often moving about in order to find better employment or affordable accommodation, whilst the terrifying spectre of the workhouse loomed ever present should they fail to find both. Not surprising then that the canals should offer a viable alternative to life on land, with their boat providing a ready source of income, and a roof over their head. For most people boats were too expensive to have built, so they turned to well established canal carriers such as Pickford’s, Fellows Morton & Clayton and coal merchants such as Samuel Barlow for employment. Most of the canals by now had been absorbed by railway companies, such as the Shropshire Union Canal and the Trent & Mersey. By the time the Allcott’s entered life on the waterways, the great heyday of canal building was over, but they continued, even into the latter years of the 20th century, to play a key role in the economy of the country.”

About Jeffrey Allen

Jeffrey is my Cousin via my Mom’s long, lost Brother and it was by chance we found each other, call it fate, call it whatever but everything happens for a reason.

On October 21st, 2021 I decided to join the Canal World forum in the hope I could find anything about the Allcott’s and the long boating history that goes with them, stretching back to the 1800’s.

On November 10th, 2021 Jeffrey messaged me believing we were related via his Dad, Oliver Allcott and, I was happy he did and to confirm that we were indeed related. We have been in touch since.

For a long time, Mom always wondered how my Uncle Oliver was doing in life and would have loved to know all that I know now when she was alive but, sadly, that was never to be. I did, however, get to show her family photos and documents that I came by in her final months, before me and Jeffrey first got in touch.

Jeffrey didn’t do this booklet for monetary gain, just as a family keepsake and it was never intended for publication. I, on the other hand, think more people should see the hard work he has put into it and, hopefully, more information can subsequently come from it in the not-so-distant future. If you think you are related to anyone mentioned in this post then please contact me here.

Regardless if you are family or not, if you are a lover of history and canal life then you will enjoy this book as much as I did.

The Allcott’s By Jeffrey Allen

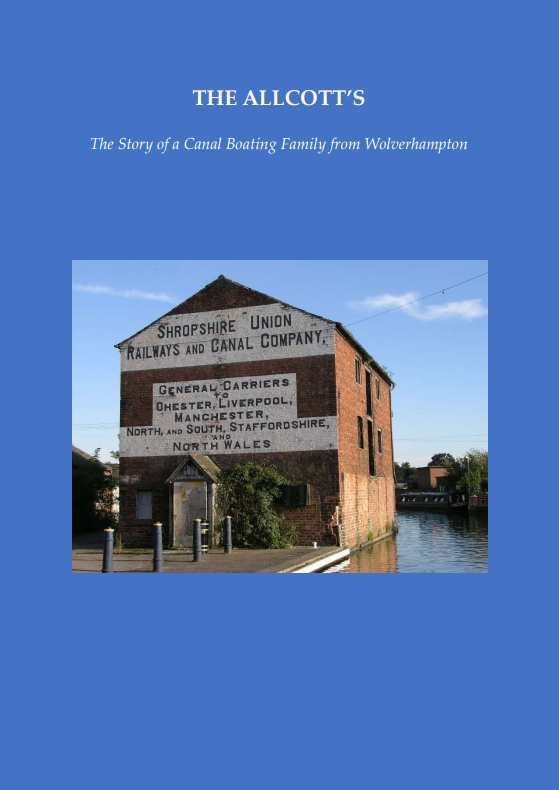

The Allcott’s

The Story of a Canal Boating Family from Wolverhampton.

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to my cousins Frank Parker and Janet Terry for supplying me with all the information on the Allcott’s. Without their kindness and love of family this booklet would not have been possible.

Dedication

In memory of my grandfather Oliver Allcott, My grandmother Beatrice Violet Allcott, Their daughter Beatrice Mary Allcott, my aunt, And their son, Oliver Allcott, my father.

Introduction

The Allcott family were typical of the many thousands of people who once turned to the canals for their livelihood during the middle and latter part of the Victorian era. Times were especially hard for the poorest people in society, often moving about in order to find better employment or affordable accommodation, whilst the terrifying spectre of the workhouse loomed ever present should they fail to find both. Not surprising then that the canals should offer a viable alternative to life on land, with their boat providing a ready source of income and a roof over their head. For most people boats were too expensive to have built, so they turned to well-established canal carriers such as Pickford’s, Fellows Morton & Clayton and coal merchants such as Samuel Barlow for employment. Most of the canals by now had been absorbed by railway companies, such as the Shropshire Union Canal and the Trent & Mersey. By the time the Allcott’s entered life on the waterways, the great heyday of canal building was over, but they continued, even into the latter years of the 20th century, to play a key role in the economy of the country.

Family History

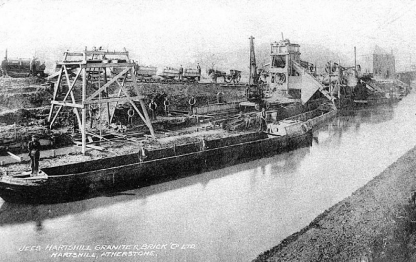

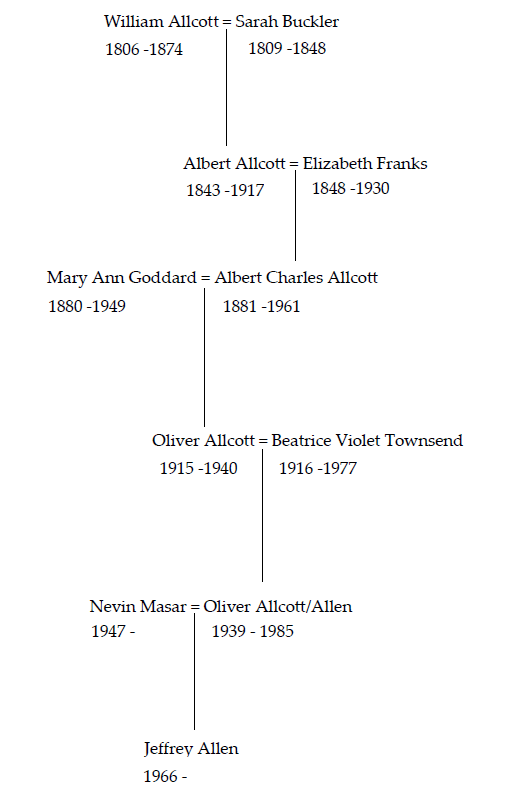

Allcott is a surname that existed in Nuneaton, Bedworth, Atherstone and Caldecote since the 17th century. Allcott derives from an Old English word eauld meaning old, and cot meaning a shelter or cottage; hence ‘a dweller in an old cottage.’ The name has its highest frequency in Herefordshire and the West Midlands. In Nuneaton for example, it first appears in records of the Quarter Sessions and Indictment Books for the years 1631-96 and the Hearth Tax of 1662. Albert Allcott was born at Hartshill, North Warwickshire, on the 17th of May 1843 to William and Sarah Allcott. Sarah (nee Buckler) was born at Bedworth on the 1st of October 1809. William was a labourer, whilst Sarah looked after their six children: Thomas (b. 20 March 1832), William (born June 15th 1833), David (born 1836), Hannah (born 1837), Sarah (born March 25th 1839) and Eliza (born 1841). Hartshill is a large village and civil parish in North Warwickshire. It borders the districts of Bedworth and Nuneaton, which is two and a half miles northwest of the village. The combined population of Bedworth and Nuneaton by 1863 was in excess of 8,600 people, and many of those were employed in silk ribbon weaving. Hartshill also borders Ansley to the south-west, where there was a coal mining colliery established in 1874; Mancetter to the north-west, Caldecote to the east, and the parish of Witherley in Leicestershire to the north-east. The market town of Atherstone is three and a half miles to the northwest. Hartshill had good communications with the rest of Warwickshire and neighbouring counties. There was a canal wharf on the Coventry Canal, (14 miles from the Coventry Basin), which served the Jees Granite & Brick Co. Ltd., which also had its own quarry. William Allcott may have worked for this company as a labourer. There was also a railway, part of the Coventry and Nuneaton branch line, with a signal box and sidings.

Not long after Albert’s birth, the family moved to Foleshill, where Sarah died in the later part of 1848 aged 39. By the mid-19th century Coventry was the centre of the ribbon trade, and at one time employed an estimated 30,000 workers, using steam-powered looms as part of a large-scale manufacturing process. William Allcott Snr. remarried two years later on the 22nd of June 1850 to Rhoda Ball from Nuneaton. The 1851 Census shows the family still living in Foleshill. William, and his son William Jnr., now aged 16, were both employed as coal miners, whilst Rhoda was a hand loom weaver, and Hannah, aged 11, was employed as a silk winder. Ten years later, both Rhoda, and her step-son Albert, now aged 18, were employed as silk weavers, whilst William was working as a day labourer. William and Rhoda had eleven children together, three boys, Henry (born June 5th 1852), Frederick (born February 28th 1858), and Joseph (born October 28th 1867); and eight girls, Emma (born September 23rd 1849), Matilda (born November 23rd 1854), Ellen (born May 8th 1856), Mary (born February 3rd 1859); all these children were born at Bedworth. Sometime after the birth of Mary in 1859, the family moved to Nuneaton, where Rose (17th of May 1863) was born, along with Sophia (22nd of May 1872) and Rhoda (31st of July 1869). Sadly, little Fanny Allcott (born 1861, Nuneaton), died when she was just three years old in 1864. Rhoda passed away in 1873 aged 47, and a year later William died aged 68. At least four of their youngest children, Rose, Sophia, Joseph and Rhoda, would not have been old enough to support themselves without their parents or older siblings.

On the 26th of March 1877 Albert Allcott, now in his mid-thirties, married Elizabeth Franks at the parish church of St Matthew, Lower Horseley Fields, Wolverhampton. His marriage certificate gives his occupation as a labourer. He may have worked for the Minerva Iron & Steel Company founded in 1857 by Isaac Jenks, who owned the Beaver Works at Lower Horseley Fields. The company exported 80% of the UK’s steel to America and had 21 puddling furnaces, 4 mills, and several forges. At one time the canal carriers Pickford’s had a wharf directly opposite the steel works at Horseley Fields.

But just four years later at the birth of their son, Albert Charles Allcott, (at Canal Street, in the town of Coseley, Wolverhampton), Albert Snr. is now a ‘boatman.’ Albert Charles was christened on the 8th of January 1882 at St Mary’s Church, Wolverhampton.

Wolverhampton was particularly noted for its iron manufacture, consisting of locks, hinges, buckles, corkscrews and japanned ware; a type of lacquer similar to shellack polish used by furniture makers. The technique of applying a heavy black lacquer originated from India, China and Japan, where it was used to glaze pottery, but in Europe, the technique was extended to small items of metal.

Trade directories from the first half of the 19th century show that there were 20 firms of japanners in Wolverhampton, ranging from small family workshops attached to the proprietor’s home to larger purpose-built factories employing between 250 to 300 workers. It is possible that Albert may have been working as a wharf labourer at Horseley Fields, where there is a junction on the Birmingham Main Line and Wyrley & Essington Canal, eventually leading to his employment as a boatman’s mate. The main advantage for families living and working on narrowboats was that money was saved on renting a house, but living conditions could be challenging. The typical cabin size would be around 8ft long by 6ft wide, and 5ft in height. Space was limited to just a couple of cupboards and a fold-out table. There was no toilet or running water aboard the vessel. Drinking water was obtained from pumps sited along the towpath and at canal wharves. The pay was low and only the skipper of the boat got paid. This meant the whole family helped to get the boat to its destination as quickly as possible, with children running ahead to open and close lock gates. The more cargo a boat could carry, the more the skipper got paid. Typical loads were around 20 – 30 tons for a single boat, but if a second boat was worked, referred to as the ‘butty,’ which was simply pulled along by the lead boat, the skipper would earn twice as much money, as well as having the additional living space of a second cabin.

On long hauls, a family might work anything up to 15, sometimes 18 hours a day in order to reduce the journey time. It was also physically demanding for both men and women, with parents sometimes ‘bow-hauling’ a vessel through lock gates, or ‘legging’ a boat through the damp and murky conditions of a tunnel; literally pushing the boat along with their feet as they lay on their backs at the stern.

It was also incredibly dangerous work, especially for young children, with death by drowning all too common. Albert Ledward aged 11 was drowned in the Bridgewater Canal in June 1876. According to the newspaper report in the Runcorn Guardian, the family left Anderton Wharf on a Wednesday afternoon:

“… with a pair of narrow boats laden with salt to be discharged at Runcorn, and when near to Bate’s Bridge at Halton, the deceased [Albert Ledward], who had had his supper, got ashore from the second boat to drive the horse, while his brother, nine years old, who had been driving, got on board to have his supper. It was then half past eleven o’clock, and dark, and as the deceased passed the first boat which he (witness) [the father] was steering, he spoke to him [Albert], and he afterwards heard him speak to the horse. When they got to the Delf Bridge the deceased came and spoke to him, and he told him to go on and get to the horse’s head, and he did. He [the father] heard him speak to the horse, and when it got near to the gas works it “shied” at a light, but again went all right until it got opposite the Soapery, when it turned back, and he (witness) called to it to stop, and it did so. He then called out to the deceased [Albert], and receiving no answer got ashore to look for him. Not seeing him, he began to feel about in the canal with a boat hook, and there being no person near but his wife, she ran for assistance, and soon brought some men and grapples, and in about half an hour the body of the deceased was found in the canal opposite to the Soapery, and near to the spot where the horse turned. He could not tell how the deceased got into the canal, for he neither heard any splash nor a scream.”

The incident at Runcorn happened just five years prior to the birth of Albert and Elizabeth’s first child, Albert Charles. By the time of the 1901 Census, Albert and Elizabeth Allcott had five children living at home, William, Joseph, Minnie, Sarah Jane and Frederick. The registration took place at Calf Heath, Wolverhampton. Calf Heath Bridge and Wharf are on the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal, which commences at a junction with the River Severn at Stourport, and terminates at Great Haywood by a junction with the Trent & Mersey Canal, once owned by the North Staffordshire Railway Company. Albert Charles was now 19 years old and living away from home. At the time of the census, he was a canal boatman’s mate aboard the Fancy, moored up at Welshpool Wharf, Montgomeryshire, a Shropshire Union Canal depot. Fancy entered service in September 1899 for the London Midland & Scottish Railway Company, and it was captained by Thomas Hyde, aged 28 from Barbridge in Cheshire. Also on board was Thomas’ wife Mary and their baby girl, Jane. Hyde may have been a relative of John Hyde, an iron merchant at Wrexham who supplied large quantities of pig iron via the Shropshire Union Canal Company to factories in Wolverhampton. The Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company (SURCCo.) was founded in 1854. The Company owned 23½ miles of railway, which was leased to the North Western Railway Company in perpetuity for a 50% dividend of North Western’s stock. They had offices in London, Birmingham, Albion Wharf at Wolverhampton, and Chester. The main line of its canal navigation was the Shropshire Union Canal from Autherley Junction near Wolverhampton to Ellesmere Port near the Wirral, a total of 66½ miles consisting of 46 locks. Thirty-eight miles into the journey from Autherley is the Nantwich Basin, the birthplace of two of Albert’s sons, William (1884) and Frederick (1895). Both went on to become boatmen.

On the 3rd of August 1903 at Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, Albert Charles married Mary Ann Goddard, aged 19 from Wolverhampton. Interestingly, Mary was born at Horseley Fields, where Albert Allcott Snr., married Elizabeth Franks some 26 years earlier. Mary’s father William was also a boatman, and it is quite possible that William Goddard and Albert Allcott had previously worked together on the same boat or stretch of canal, forming a life-long friendship between the two families, eventually leading to kinship through the marriage of their children. William’s father, Richard Goddard (1822 – 1883), first appears in the records as a boatman in 1851 at Brook Lane Wharf, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire. In subsequent census’ he is to be found aboard canal boats Lincoln (1861), Emily (1871), and Birmingham (1881). The Goddard’s may have been instrumental in introducing Albert Allcott Snr. to life on the canals. Ellesmere Port is six miles north of Chester and eleven miles south of Liverpool. In 1905 the Wolverhampton Corrugated Iron Company built a factory at Ellesmere, employing 300 workers and their families from Wolverhampton. The company was seeking to exploit its international trade through nearby ports of Birkenhead and Liverpool. The community that grew up around the factory was affectionately referred to as ‘Wolverham.’ The following year Mary gave birth to their first child, Minnie Allcott, at Ellesmere Port. Canal boat Snap was given as the family residence, and Minnie was delivered by Harriet Didsbury, midwife, living at no. 6 Porters Row, Whitley, a row of Victorian cottages built in 1833 to house canal workers and their families. Snap was a SURCCo. boat working the Shropshire Union Canal. Albert Charles and Mary had three more children, Frederick (1905), Sarah Ann (1908) and Albert (1911). Albert Allcott Snr. was 68 at the time of the 1911 Census. He may have been retired from the boats as his occupation was not recorded. Times may have been hard for the family as Elizabeth was said to be a ‘washerwoman,’ and Sarah Jane, aged 17, was a ‘presser’ for a company manufacturing iron brackets. In those days a typical working-class family budget would have been around 22 shillings a week, with bread, flour and meat alone costing around 8s, more than a third of the household budget. Rent could be anywhere between 3 to 5s a week.

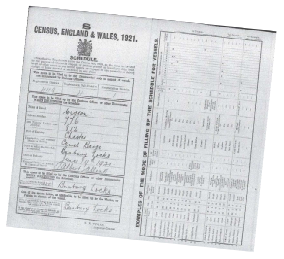

Their youngest son Frederick was 15 at the time of the census and a boatman’s mate aboard the canal boat Jim, moored at Etruria Locks, Stoke on Trent. The master was William Mallard aged 32 and his wife Emma and two children James and Mary. Their niece Elizabeth Clewes aged 18 was the third mate. Jim worked the Trent & Mersey Canal navigation. Fred’s older brother Joseph, aged 24, was a boat hand on a Shropshire Union Canal boat the Flying Fox. Flying Fox was registered on the 13th of June 1899 at Chester, reg. 550, and entered service for the SURCCo. in August 1899 fleet no. 529. As her name suggests, she may well have been a ‘fly-boat.’ Flyboats usually carried smaller loads of high-value merchandise, with a two-man crew working day and night. A fly boat could travel from Ellesmere Port to Birmingham in little more than 36 hours. In its heyday, Pickford’s specialised in the fly-boat trade, with 116 boats and 398 horses. It was an offence enforceable by law not to give their boats right of way at lock gates. By 1925 Joseph was working for the Midlands & Coastal Canal Carriers Ltd., transporting goods between Stoke-on-Trent and Ellesmere Port. He is recorded as being on their boat Mermaid, originally a motor boat registered in Wolverhampton, no. 1118. Its engines were removed in the same year, turning it into a butty. Joseph was also on a MCCC boat called Diamond, first registered in 1922 at Wolverhampton, (no. 1088). Since Albert Allcott Snr. was living in Wolverhampton at the time of the 1911 Census, the Albert Allcott mentioned as master of the Winconsin, must refer to his son Albert Charles. Winconsin was moored at the Anderton Wharf, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, working the Trent & Mersey Canal. His son Albert Jnr. was born at Rode Heath, Cheshire, (1911), where the Trent & Mersey runs through the middle of the village. Four years later and Mary Ann gave birth to their fifth child, Oliver Allcott, on the 2nd of June 1915. The family residence was given as canal boat Sutherland, moored at Hay Basin, Broad Street, Wolverhampton. Built by Calder Valley Marine, Sutherland belonged to the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company, fleet no. 481, and was ‘gauged’ for the Birmingham Canal Navigations in 1896. When war raged across Europe in 1914, Frederick Allcott enlisted in the 2nd Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment, at Wolverhampton. Fred was killed in action at Delville Wood, the Somme, after a German counter attack on the 28th of July 1916. He was just 21. His personal effects were returned to his family on the 4th of November 1916, along with £5 6d to his father, Albert Allcott Snr. On the 21st of October 1919, his mother Elizabeth Allcott received a further payment from the army of £9. Fred’s name can be found on the Common Wealth War Graves Commission memorial at Thiepval, the Somme, and on the Roll of Honour of the London and North Western Railwaymen; because he had been employed as a boatman at Wolverhampton delivering coal to the railways. Six months after the loss of his son, Albert snr., the first Allcott to have started work on the narrowboats, died on the 13th of February 1917, at no. 2 Southampton Street, Wolverhampton; Elizabeth, his dutiful wife of 40 years, was at his bedside. By the time of the 1921 Census, held on the 19th of June, Albert Charles was skipper of the canal boat Widgeon, moored at Bunbury Locks, on the Shropshire Union Canal. Originally built for the Chester & Liverpool Lighterage Co. Ltd., Widgeon joined the SURCCo. in March 1917, fleet no. 776. It was registered at Chester on the 10th of April 1917, registration no. 812.

Two years after the census, on the 27th of October 1923, Albert Charles’ eldest daughter Minnie, aged 19, married John Pountney, himself a boatman aged 32. Canal boat Cardigan was given as the residence of both Minnie and John on their marriage certificate. Cardigan was a Fellows Morton & Clayton boat, fleet no. 42, built at Uxbridge Docks (West London), and entered service in January 1906, registration no. Uxbridge 401.

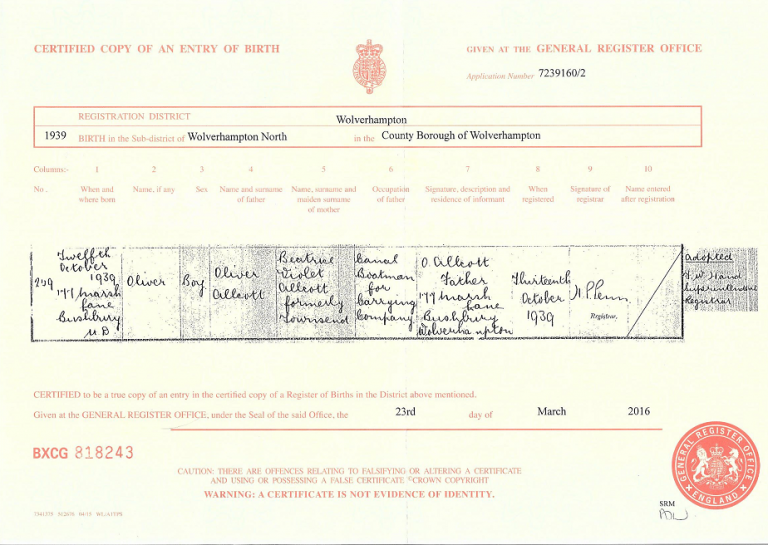

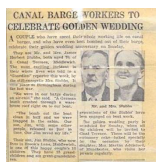

Thirteen years after the death of her husband Albert, Elizabeth Allcott died at no. 9 Barker Street, Wolverhampton, on the 10th of January 1930, aged 73. She never got to see the marriage of her son Oliver to Beatrice Violet Townsend on the 8th of April 1935. They were married at the parish church of St Chads, Staffordshire, in the presence of Ernest Williams and Sarah Ann Williams. Their address was given as 120, Jeffcock Road, Wolverhampton, but as Oliver was, like his father and grandfather before him, a boatman, it is likely that his boat was moored nearby on the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal, and that Jeffcock Road was a temporary residence used for the purposes of official registration. On the 28th of January 1936, Beatrice gave birth to the couple’s first child, Beatrice Mary Allcott. The address was given as no. 19, Purcel Road, Low Hill, Wolverhampton. Three years later Beatrice gave birth to a son, Oliver Allcott Jnr., this time at 177 Marsh Lane, Bushbury, Wolverhampton, on the 12th of October 1939.

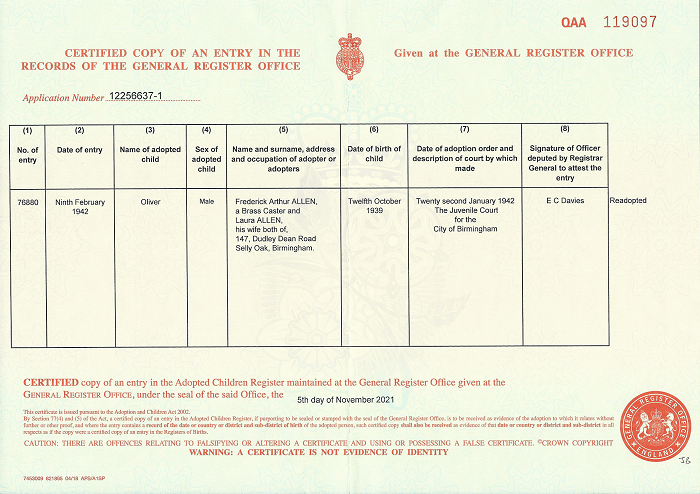

By now Oliver Snr. was seriously ill with tuberculosis, and little more than five months after the birth of his son, he passed away on the 9th of February 1940 aged just 24. He died at 376 Wolverhampton Road, Heath Town, a pseudonymous address of the former New Cross Workhouse, which became a hospital in 1930. Although officially a hospital, it still performed some of the services of the former workhouse. The death certificate gives Oliver’s occupation as ‘a Wharf Labourer for Coal Merchant,’ possibly Samuel Barlow. Two years after the death of his father, Oliver Allcott Jnr. was adopted by Frederick and Laura Allen on the 22nd of January 1942. Laura (nee Townsend) was the older sister of Beatrice Violet Allcott, so the two-year-old Oliver was being adopted by his own aunt. The couple were living at no. 147, Durley Dean Road, Selly Oak, Birmingham.

Unlike the Allcott’s, the Townsend family were involved in Birmingham’s enormous metal industry, with the family home, 37 Tower Street, not far from the famous Jewellery Quarter. In 1921, Laura was a ‘capstan lathe’ operator, putting threads on metal items usually made of brass. She may have worked for Young’s Ltd at their Ryland Street works, Edgbaston, where her younger brother Albert, aged 14, was employed as an errand boy.

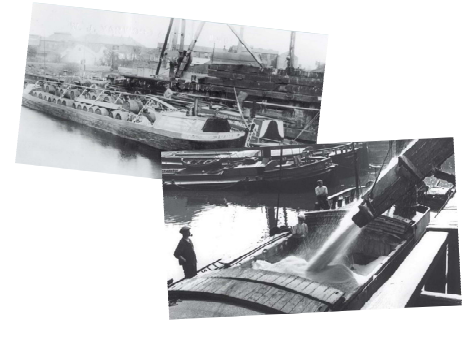

Although the canal boating tradition had come to an end for one branch of the Allcott family, it continued for another. During the Second World War, William Allcott, the eldest son of Albert and Elizabeth Allcott, was working for the Grand Union Canal Carrying Company, transporting cargoes such as coal, steel, timber and grain between London and the Midlands.

According to a manning list of paired boats for September 1944, William was the skipper of Arcas and Malus. Arcas was built by Harland and Wolff Ltd on the 16th of November 1935, and registered at Brentford, West London, on the 18th of December 1935, no. 558. She was gauged for the Grand Union Canal on the 20th of October 1936, gauge no. 12582. Malus (the butty) was built by W. J. Yarwoods & Sons of Northwich in September 1935. It was delivered on the 4th of October 1935, fleet no. 307 and registered at Coventry no. 535. She was gauged on the Grand Union Canal on the 24th of October 1936, and given the gauge no. 12412. Arcas and Malus were part of the company’s expansion program of its Southern Division during the 1930’s and 1940’s.

William’s family lived near Stowe Hill Wharf, Heyford Lane, in the village of Weedon Bec, Northamptonshire, about 6 miles south of the market town of Daventry.

The Second World War brought with it hazards all of its own, with thousands of German bombs raining down on Birmingham in Hitler’s effort to destroy Britain’s manufacturing base. During the war, Eliza Stubbs (nee Goddard) and her husband James were working for Fellows Morton & Clayton and moored up in Birmingham. Eliza was the sister-in-law of Albert Charles Allcott. Albert and his future wife Mary Ann Goddard, (Eliza’s sister), were witnesses to the wedding of Eliza and James at Ellesmere Port on the 25th of May 1903. “We were in our barge during an air-raid,” recalled Eliza. “A German bomb crashed through a warehouse roof right on to our boat. The bomb cut the boat clean in half and we were trapped in the cabin. Our son, Jim, with some other people, released us just in time.” Eliza and James were one of the 622 families then living and working on the waterways, helping to transport an estimated 12 million tonnes of essential goods a year on Britain’s canals.

A year after nationalisation took place in Britain, Albert Charles Allcott remarried in 1949 following the death of Mary Ann. His bride was Sarah Emma Shaw (nee Stubbs), sister of James Herbert Stubbs, who was also Albert Charles’ best man at the wedding. The reception was held at no. 3, Canal Terrace, Middlewich, Cheshire, the family home of Eliza and James.

The Middlewich Branch of the Shropshire Union Canal runs through the town before joining the Trent & Mersey Canal at Wardle Lock. In 1826 authorization had been given for the section of canal at Middlewich to join with the Trent & Mersey, linking Chester with the potteries in the Midlands. The Great Heywood Junction is 19 miles from Stoke-On-Trent, which connects to the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal with Wolverhampton. Albert died on the 18th of December 1961 at 175 Marsh Lane, Wolverhampton, aged 80. The boating tradition was carried on in the next generation of the Allcott’s. According to an article in Narrowboat Magazine, ‘British Waterways Boating’ (Spring 2018), two boats, Purton and Capella, were worked by Joseph and Lucy Allcott in the 1950’s and 1960’s on the Grand Union Canal. Joseph Allcott was born at Wolverhampton in 1927, the son of William Allcott (b. 1884). Lucy Elizabeth Jackson was five years older, being born at Northampton in 1922. They married at Brixworth, Northamptonshire on the 24th of September 1951. Along with her father Thomas Jackson, Lucy was already employed by British Waterways, a ‘boatwoman’ in her own right.

Purton was built by W.J. Yarwoods & Sons Ltd. with a National DM2 engine and joined the GUCCCo. in September 1936 fleet no. 162. She was registered at Rickmansworth on the 20th of October 1936, registration no. 104, and gauged for the Grand Union Canal on the 7th of November 1936, gauge no. 12614.

Capella (the butty) was built by Harland & Wolf Ltd. and joined the GUCCCo. in December 1935, fleet no. 247. She was registered at Brentford on the 18th of December 1935, registration no. 572, and gauged for the Grand Union Canal in December 1935, gauge no. 12549.

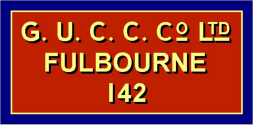

Sometime during the 1960’s British Waterways gave Purton a new Lister HA2 engine, and shortened its length to approximately 56ft. She was eventually sold off in 1987 when the transportation of goods by canal boat finally came to an end. Joseph was the steerer of Purton from January 1951 to August 1956, but not always with Capella as the butty; others included Ruislip, Asla and Hadfield. According to the Birmingham Public Health Department records, by March 1957 Joseph was steering a 72ft motor boat called Fulbourne, with Chesham as its butty. Fulbourne was built by Harland & Wolf at Woolwich and was completed in March 1937. She is a steel-hulled motor boat in the ‘Town Class’ of narrow boats, so named because twenty-four of them were named after British towns. Fulbourne was registered at Rickmansworth and gauged for the Grand Union Canal, no. 12740. She remained in the GUCCCo. fleet until nationalisation in 1947. British Waterways fleet lists from May 1958 to January 1959 show that Joseph and Lucy were still on Fulbourne, with Halton as the butty. During his time on Fulbourne, Joseph carried coal to Apsley, Colne Valley Sewage Works, Croxley and Nash Mill. They delivered grain to Wellingborough on the River Nene, took spelt from Brentford to Birmingham, and lime juice from Limehouse to Boxmoor. On one occasion they took the boat to Weston Point on the Manchester Ship Canal to unload a ship, but since the dockers were on strike at the time, they were turned away and had to pick up an alternative cargo elsewhere. Joseph died aged 61 on the 4th of December 1988. Lucy passed away eight years later in the June quarter of 1996.

Postscript

Of the many newspaper reports throughout the canal network from 1881 to 1936, the Allcott’s feature in none of them. Whilst some boaters were often in trouble with the law for theft, drunkenness, and often cruelty to their animals, (and occasionally to each other), the Allcott’s were a peaceable hardworking family. The four main canal systems they worked, from Ellesmere Port in the north west, to London in the south east, spanned some 255 miles with a total of 207 locks, but Wolverhampton remained their home base for many years. With a great sense of pride, it has been my privilege to learn about the Allcott family, the many relatives connected to them, and how they lived and worked on Britain’s inland waterways.

Jeffrey Allen

March 23rd, 2022

Oliver Allen (Allcott), October 12th 1939 – July 6th 1986

This booklet has been a journey of discovery. My father, Oliver Allen, never knew his real parents. All that he had been told by his adoptive parents Fred and Laura, was that he was born on the 12th of October 1939 in Wolverhampton and that he had been adopted. He thought his original surname was Parker, and that he may have had a sister. It was not until the end of last year, 2021, that I finally, by pure chance, found a blood relative whilst searching online, my first cousin Frank Parker. Through Frank and his sister Janet, the story of the Allcott family slowly began to emerge, and the tragic circumstances which led to my father’s adoption in 1942. The great irony is, for all those years we lived in Daventry, he was actually surrounded by living descendants of the Allcott family. Some were living in the town itself, whilst others were working in the neighbouring villages of Weedon Bec and Braunston. In accordance with his wishes, my father’s ashes were scattered on Screel Hill, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, where we spent many a happy family holiday.

July 6th, 2022

Addendum

The following is not in the above booklet and some information and photo’s are repeated but there is further information on the Allcott’s.

Canal Boats Worked By The Allcott Family From 1881 – 1944 By Jeffrey Allen

1877 – 1881

Albert Allcott (born 1843 – died 1917) was the first family member to work the canal boats, sometime between the 26th of March 1877 and the 13th of December 1881. His occupation at the time of the 1861 Census was ‘silk weaver,’ and by the time of his marriage to Elizabeth Franks in 1877, he was a labourer. They were married at the Parish Church of St Matthew in Lower Horseley Fields, Wolverhampton, where there is a junction between the Birmingham Main Line and the Wyrley & Essington Canal. It’s possible that Albert was working as a wharf labourer loading the barges before he became a boatman himself. By the time of his first child, Albert Charles Allcott in 1881, Albert’s occupation is recorded as ‘Boatman,’ with the family residence given as Canal Street in the town of Coseley, Wolverhampton.

1901

FANCY (SURCCo.)

Shropshire Union Canal

In the 1901 Census, Albert was a mate aboard the FANCY, moored at Welshpool Wharf, a Shropshire Union Canal depot. FANCY entered service in September 1899 for the LMS Railway, fleet no. 534. Registration no. Chester 555.

The Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company (SURCCo.) was founded in 1854. The Company owned 23½ miles of railway, which was leased to the North Western Railway Company in perpetuity for a 50% dividend of North Western’s stock. They had offices in London, Birmingham, Albion wharf at Wolverhampton, and Chester. The main line of its canal navigation was the Shropshire Union Canal from Autherley Junction near Wolverhampton to Ellesmere Port near the Wirral, a total of 66½ miles consisting of 46 locks. Thirty-eight miles into the journey from Autherley is the Nantwich Basin, Cheshire, the birthplace of two of Albert’s sons, William (1884) and Frederick (December 1895). Frederick was baptised at Lilleshall, Shropshire on January the 18th 1896. Both men went on to become boatmen.

Frederick Allcott

1904

SNAP (SURCCo.)

Shropshire Union Canal

Given as the family residence at Ellesmere Port, Whitley, on the birth certificate of Minnie Allcott (born 1904 – died 1968).

1911

WINCONSIN & JIM

Trent & Mersey Canal

In the 1911 Census, Albert was master of the WINCONSIN moored at Anderton Wharf, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire.

At the time of the 1911 Census, Frederick Allcott was 15 years old and worked as a canal boat mate, the master was William Mallard aged 32. The address was given as Etruria Locks, Stoke on Trent, Staffordshire. Frederick enlisted in the 2nd Batallion, South Staffordshire Regiment, at Wolverhampton.

Rank: Private, Service No. 16384, Frederick was killed in action at the Battle of the Somme in 1916 in the Battle of Delville Wood. You can read more about Delville Wood here.

He was commemorated on the roll of honour of the London and North Western Railwaymen.

You can read more about Thiepval Memorial, France here.

1915

SUTHERLAND (SURCCo.)

Shropshire Union Canal

Built by Calder Valley Marine, SUTHERLAND belonged to the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company, fleet no. 481, and was gauged for the Birmingham Canal Navigations in 1896. It was a powered motor boat 17.68 metres (58 ft) long, with a beam of 2.14 metres (7 ft) wide. It was a long-distance cabin boat in which the steerer plus family (and/or mate) would have been resident, at least when in transit, if not as their home. It was given as the family’s address on the birth certificate of Oliver Allcott, 2nd of June 1915, Hay Basin, Broad Street, Wolverhampton. Albert Charles Allcott was the steerer. Registered with the Canal & River Trust, No. 512465.

1923

CARDIGAN (FM&C)

Coventry Canal

Given as the family residence of Minnie Allcott and John Pountney on their marriage certificate, October 27th 1923. CARDIGAN was moored near the Foleshill Road, Coventry. Possibly a boat of Fellows Morton & Clayton, a nation-wide canal carrying company, fleet no. 42, built at Uxbridge Dock (West London), entered service in January 1906. Registration no. Uxbridge 401.

1944

ARCAS & MALUS (GUCCCo. paired boats, fleet no. 11)

Grand Union Canal

According to a manning list of paired boats for September 1944, William Allcott (born 1884) was working for the Grand Union Canal Carrying Company during WW2 on canal boats ARCAS and MALUS. The family lived at Stowe Hill Wharf, Heyford Lane, in the village of Weedon Bec, Northamptonshire. (Weedon is 6 miles from the market town of Daventry, where I grew up. We moved to Daventry in about 1969, living at 109 Hemans Road).

ARCAS was built by Harland and Wolff Ltd and entered service in November 1935. Registration no. Brentford 558 (West London).

MALUS (the butty) was built by W. J. Yarwoods & Sons of Northwich in September 1935 for the GUCCCo. It was delivered on 4 October 1935, fleet no. 307. Registration no. Coventry 535. She was gauged on the Grand Union Canal on October 24th 1936, and given the gauging number 12412. She was used for the carriage of cargoes such as coal, steel, timber and grain from London to the Midlands. In order to remain profitable, boatmen/boatwomen didn’t like to run between jobs without cargo. To avoid this some on the London run would load up with cocoa or chocolate crumbs before returning to Cadbury’s in the Midlands.

Blog Posts

Notes And Links

Download The Allcotts in PDF format by clicking here.

Read an online e-book version of The Allcott’s here.

Roger Kidd’s page on Geograph – The Marsh Lane image above is the copyright of Roger Kidd. Here you will find more great work from the photographer Roger.

Geograph – The Geograph Britain and Ireland project offers lots of free, good-quality images and aims to collect geographically representative photographs and information for every square kilometre of Great Britain and Ireland, and you can be part of it.