The terminology used for describing motion pictures varies considerably between British and American English. In British usage, the name of the medium is film. The word movie is understood but seldom used. Additionally, the pictures (plural) is used semi-frequently to refer to the place where movies are exhibited, while in American English this may be called the movies, but it is becoming outdated. In other countries, the place where movies are exhibited may be called a cinema or movie theatre. By contrast, in the United States, movie is the predominant form. Although the words film and movie are sometimes used interchangeably, film is more often used when considering artistic, theoretical, or technical aspects. The term movies more often refers to entertainment or commercial aspects, such as where to go for a fun evening on a date. For example, a book titled How to Understand a Film would probably be about the aesthetics or theory of film, while a book entitled Let’s Go to the Movies would probably be about the history of entertaining movies and blockbusters.

Further terminology is used to distinguish various forms and media used in the film industry. Motion pictures and moving pictures are frequently used terms for film and movie productions specifically intended for theatrical exhibition, such as, for instance, Star Wars. DVD and videotape are video formats that can reproduce a photochemical film. A reproduction based on such is called a transfer. After the advent of theatrical film as an industry, the television industry began using videotape as a recording medium. For many decades, the tape was solely an analogue medium onto which moving images could be either recorded or transferred. Film and filming refer to the photochemical medium that chemically records a visual image and the act of recording respectively. However, the act of shooting images with other visual media, such as with a digital camera, is still called filming and the resulting works are often called films as interchangeable with movies, despite not being shot on film. Silent films need not be utterly silent but are films and movies without an audible dialogue, including those that have a musical accompaniment. The word, Talkies, refers to the earliest sound films created to have audible dialogue recorded for playback along with the film, regardless of a musical accompaniment. Cinema either broadly encompasses both films and movies, or it is roughly synonymous with film and theatrical exhibition, and both are capitalised when referring to a category of art. The silver screen refers to the projection screen used to exhibit films and, by extension, is also used as a metonym for the entire film industry.

Widescreen refers to a larger width to height in the frame, compared to earlier historic aspect ratios. A feature-length film, or feature film, is of a conventional full length, usually 60 minutes or more, and can commercially stand by itself without other films in a ticketed screening. A short is a film that is not as long as a feature-length film, often screened with other shorts, or preceding a feature-length film. An independent is a film made outside the conventional film industry.

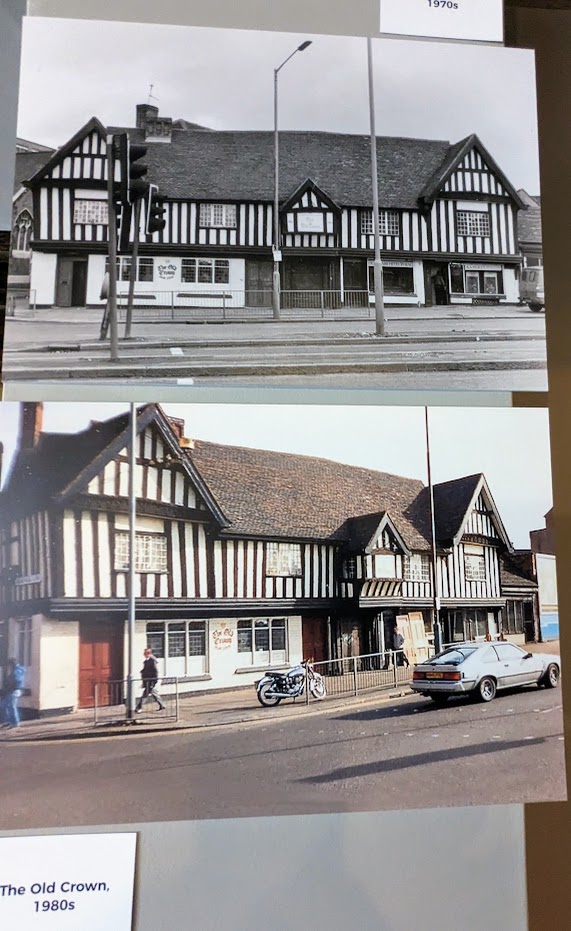

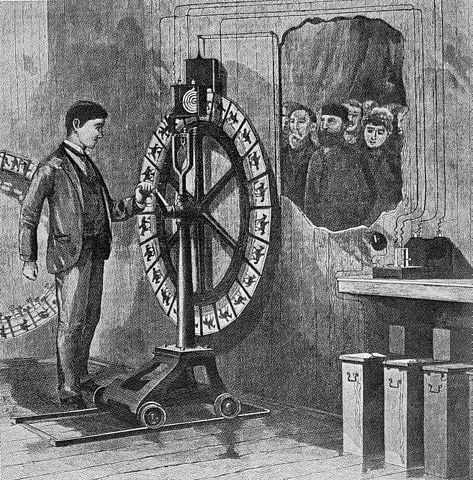

In U.S. usage, one talks of a screening or projection of a movie or video on a screen at a public or private theatre. In British English, a film showing happens at a cinema, never a theatre, which is a different medium and place altogether. A cinema usually refers to an arena designed specifically to exhibit films, where the screen is affixed to a wall, while a theatre usually refers to a place where live, non-recorded action or combination thereof occurs from a podium or other type of stage, including the amphitheatre. Theatres can still screen movies in them, though the theatre would be retrofitted to do so. One might propose going to the cinema when referring to the activity, or sometimes to the pictures in British English, whereas the U.S. expression is usually going to the movies. A cinema usually shows a mass-marketed movie using a front-projection screen process with either a film projector or, more recently, with a digital projector. But, cinemas may also show theatrical movies from their home video transfers that include Blu-ray Disc, DVD, and videocassette when they possess sufficient projection quality or based upon need, such as movies that exist only in their transferred state, which may be due to the loss or deterioration of the film master and prints from which the movie originally existed. Due to the advent of digital film production and distribution, physical film might be absent entirely. A double feature is a screening of two independently marketed, stand-alone feature films. A viewing is a watching of a film. Sales and at the box office refer to tickets sold at a theatre, or more currently, rights sold for individual showings. A release is the distribution and often simultaneous screening of a film. A preview is a screening in advance of the main release.

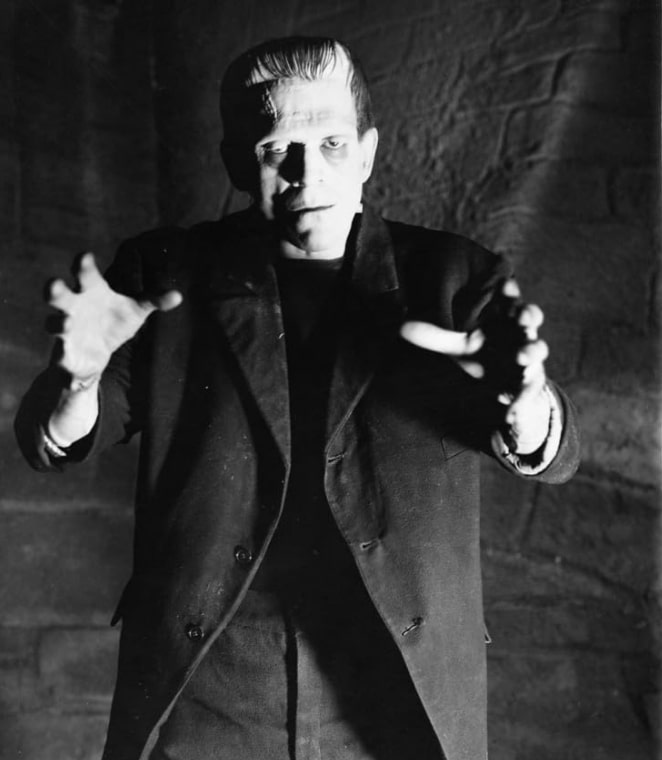

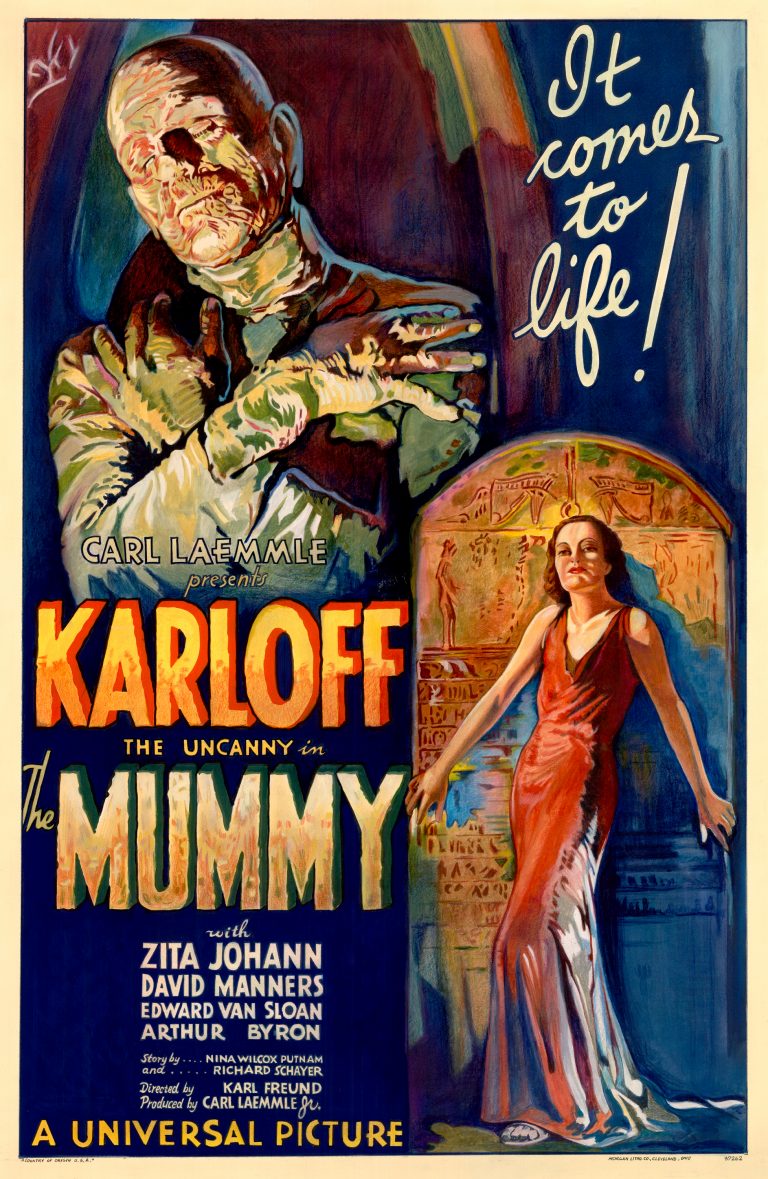

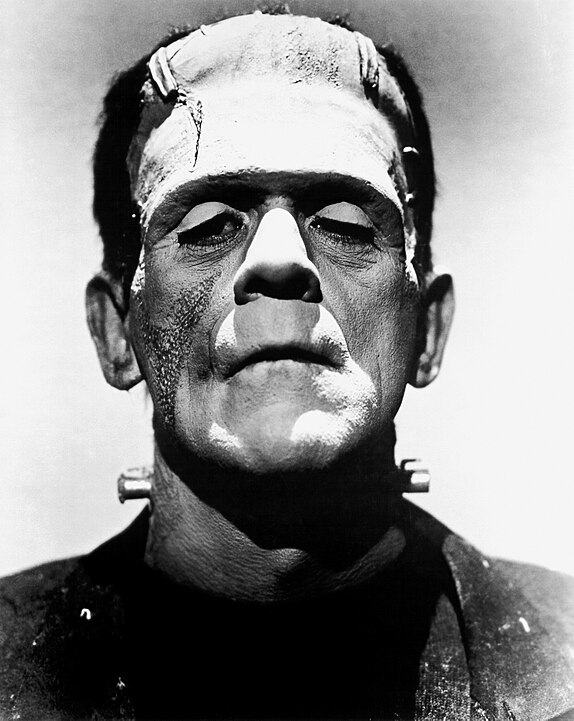

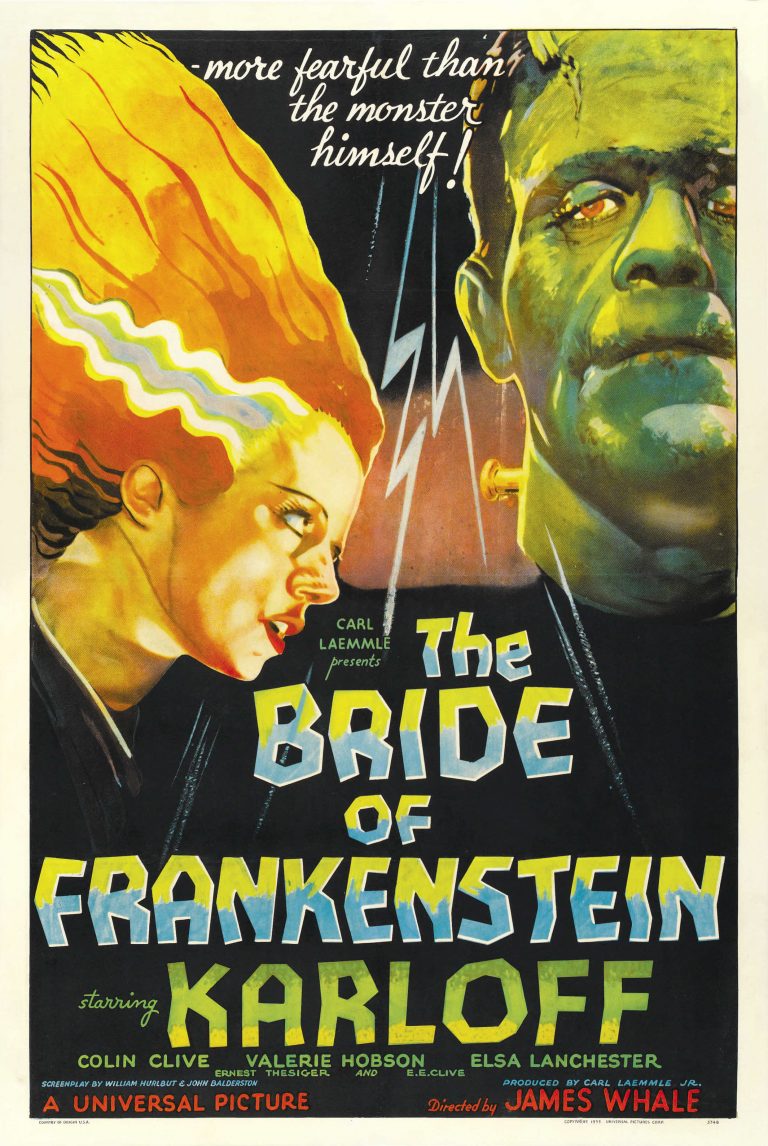

Any film may also have a sequel, which portrays events following those in the film. Bride of Frankenstein is an early example. When there are more films than one with the same characters, story arcs, or subject themes, these movies become a series, such as the James Bond series. And, existing outside a specific story timeline usually, does not exclude a film from being part of a series. A film that portrays events occurring earlier in a timeline with those in another film, but is released after that film, is sometimes called a prequel, an example being Butch and Sundance: The Early Days.

The credits, or end credits, are a list that gives credit to the people involved in the production of a film. Films from before the 1970’s usually start a film with credits, often ending with only a title card, saying The End or some equivalent, often an equivalent that depends on the language of the production. From then onward, a film’s credits usually appear at the end of most films. However, films with credits that end a film often repeat some credits at or near the start of a film and therefore appear twice, such as that film’s acting leads, while less frequently some appearing near or at the beginning only appear there, not at the end, which often happens to the director’s credit. The credits appearing at or near the beginning of a film are usually called titles or beginning titles. A post-credits scene is a scene shown after the end of the credits. Ferris Bueller’s Day Off has a post-credit scene in which Ferris tells the audience that the film is over and they should go home.

A film’s cast refers to a collection of the actors and actresses who appear, or star, in a film. A star is an actor or actress, often a popular one, and in many cases, a celebrity who plays a central character in a film. Occasionally the word can also be used to refer to the fame of other members of the crew, such as a director or other personality, such as Martin Scorsese. A crew is usually interpreted as the people involved in a film’s physical construction outside cast participation, and it could include directors, film editors, photographers, grips, gaffers, set decorators, prop masters, and costume designers. A person can both be part of a film’s cast and crew, such as Woody Allen, who directed and starred in Take the Money and Run.

A film goer, movie goer, or film buff is a person who likes or often attends films and movies, and any of these, though more often the latter, could also see oneself as a student of films and movies. Intense interest in films, film theory, and film criticism, is known as cinephilia. A film enthusiast is known as a cinephile or cineaste.