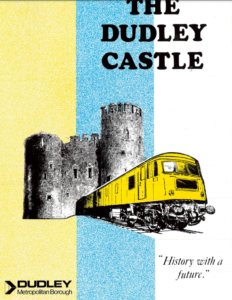

By the early 16th century the Dudley estate, now held by the Sutton family, had become severely in debt and was first mortgaged to distant relative John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, before being sold outright in 1535. Following Dudley’s execution in 1553, the estate returned to the Sutton family, during whose ownership the town was visited by Queen Elizabeth during a tour of England.

In 1605, conspirators of the Gunpowder Plot fled to Holbeche House in nearby Wall Heath, where they were defeated and captured by the forces of the Sheriff of Worcestershire.

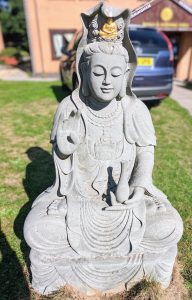

During the English Civil, War Dudley served as a Royalist stronghold, with the castle besieged twice by the Parliamentarians and later partly demolished on the orders of the Government after the Royalist surrender. It is also from around this time that the oldest excavated condoms, found in the remains of Dudley Castle, were believed to have originated.

Dudley had become an incredibly impoverished place during the 16th and 17th centuries, but the advent of the Industrial Revolution began to reverse this trend. In the early 17th century, Dud Dudley, an illegitimate son of Edward Sutton, 5th Baron Dudley and Elizabeth Tomlinson, devised a method of smelting Iron ore using coke at his father’s works in Cradley and Pensnett Chase, though his trade was unsuccessful due to circumstances of the time. Abraham Darby was descended from Dud Dudley’s sister, Jane, and was the first person to produce iron commercially using coke instead of charcoal at his works in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire in 1709. Abraham Darby was born near Wrens Nest Hill near the town of Dudley and it is claimed that he may have known about Dud Dudley’s earlier work.

Dud Dudley’s discovery, together with improvements to the local road network and the construction of the Dudley Canal, made Dudley into an important industrial and commercial centre. The first Newcomen steam engine, used to pump water from the mines of the Lord Dudley’s estates, was installed at the Conygree coal works a mile east of Dudley Castle in 1712, though this is challenged by Wolverhampton, which also claims to have been the location of the first working Newcomen engine.

Read more here.

The above articles were sourced from Wikipedia and are subject to change.