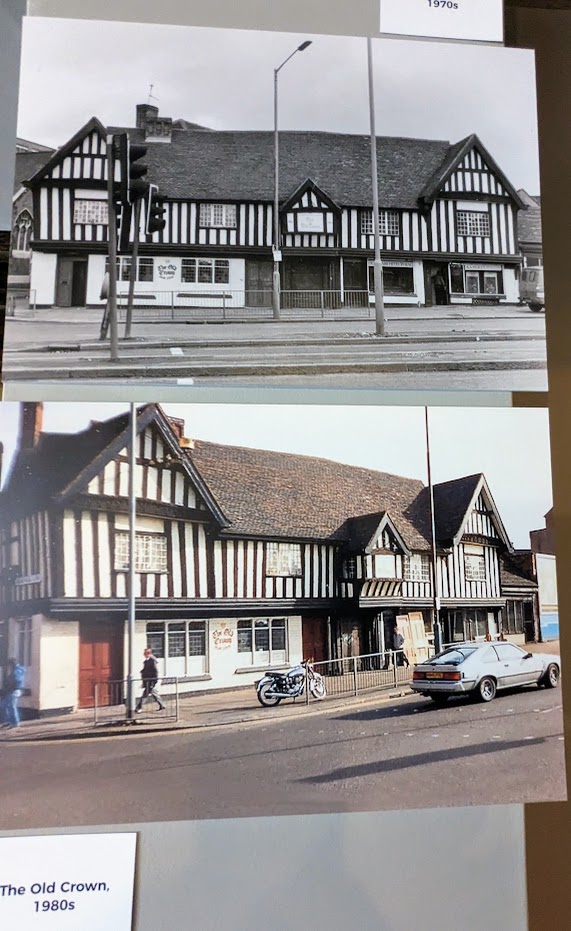

Bonfire Night always brings back happy memories over the decades, especially family ones from when I was younger in the 70’s and ’80s.

It is a great tradition that brings people together to watch a bonfire and/or watch fireworks and/or (for many) have a party with food and drink.

I don’t like being too near a fire as the flames have always been quite scary and made me nervous since I was younger but it fascinates me too, watching the shapes in the flames, the different colours and listening to the sounds of it are mesmerising.

When it is just me and I have a bonfire at home, it is a chance to sit by it (weather permitting), have some baked potatoes and reminisce about the Bonfire Night’s that has passed in time.

I think of the times I have made/helped make a Guy over the years. They have been filled with loads of leaves out of the gardens, newspaper and old clothes.

Once (in the 70’s) I glued a Guy Fawkes mask on an old cereal packet cut out from my favourite comic, Whoopee! You can see the design below.

I used to like going out with my Sister Julie and Brother Bill to do Penny For The Guy.

I remember having sparklers and writing my name in the dark night (although I wore gloves as they scared me and still this day I am not a great fan of them and can’t hold one).

I remember my Dad keeping fireworks in a biscuit tin, chestnuts cooked in the bonfire ashes, and my Mom bringing sweets out in another tin and piping hot baked potatoes wrapped in foil in another tin ready to add loads of butter/margarine, yummy!

I think of when my son Frank Jnr. and Daughter Debbie were younger and taking them to the bonfires at their Nan and Grandad’s and having bonfires with them at home (when it was possible). I remember when they were older and left home but came to visit and share the tradition with me. Jnr. as came with my Grandson Tyler and Deb came with my Grandaughter Kasey (when my grandkids were younger) and on those occasions, Mom was there all excited when the fireworks went off.

Speaking of fireworks I remember one time at a bonfire night at home, Dad picked up a jumping jack and thinking it was dead threw it in the bonfire and it shot out and hit the wall behind and above to the left of me and a friend, by a few feet. Luck was on our side that day, ha ha.

All these are wonderful memories now Mom and Dad are no longer with us.

Although it will never be as magical as it was back in the day, it is a tradition that I will celebrate at home by having a bonfire whatever the size of it (if there is anything to burn that is), have baked potatoes and finish Bonfire Night watching V For Vendetta as long as I can. Traditions mean a lot to me.

About Bonfire Night

Bonfire Night, also known as Guy Fawkes Night, Guy Fawkes Day, and Fireworks Night, is an annual commemoration observed on the 5th of November, primarily in Great Britain, involving bonfires and fireworks displays. Its history begins with the events of the 5th of November, 1605, when Guy Fawkes, a member of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding explosives the plotters had placed beneath the House of Lords. The Catholic plotters had intended to assassinate Protestant king James I and his parliament. Celebrating that the king had survived, people lit bonfires around London. Months later, the Observance of 5th of November Act mandated an annual public day of thanksgiving for the plot’s failure.

Within a few decades Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was known, became the predominant English state commemoration. As it carried strong Protestant religious overtones it also became a focus for anti-Catholic sentiment. Puritans delivered sermons regarding the perceived dangers of popery, while during increasingly raucous celebrations common folk burnt effigies of popular hate figures, such as the Pope. Towards the end of the 18th century reports appeared of children begging for money with the effigies of Guy Fawkes and the 5th of November gradually became known as Guy Fawkes Day. Towns such as Lewes and Guildford were in the 19th-century scenes of increasingly violent class-based confrontations, fostering traditions those towns celebrate still, albeit peaceably. In the 1850’s changing attitudes resulted in the toning down of much of the day’s anti-Catholic rhetoric, and the Observance of the 5th November Act was repealed in 1859. Eventually, the violence was dealt with, and by the 20th century, Guy Fawkes Day had become an enjoyable social commemoration, although lacking much of its original focus. The present-day Bonfire Night is usually celebrated at large organised events.

Settlers exported Guy Fawkes Night to overseas colonies, including some in North America, where it was known as Pope Day. Those festivities died out with the onset of the American Revolution. Claims that Guy Fawkes Night was a Protestant replacement for older customs such as Samhain are disputed.

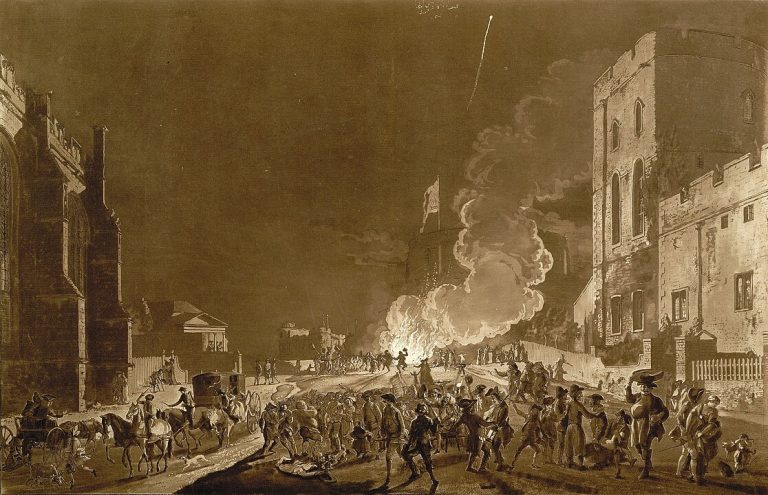

Festivities in Windsor Castle during Guy Fawkes night in 1776.

This is by artist Paul Sanby and is one of a group of four prints of Windsor Castle.

The Origins And History Of Bonfire Night

Guy Fawkes Night originates from the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a failed attempt by a group of provincial English Catholics to assassinate the Protestant King James I of England and VI of Scotland and replace him with a Catholic head of state. In the immediate aftermath of the November 5th arrest of Guy Fawkes, caught guarding a cache of explosives placed beneath the House of Lords, James’s Council allowed the public to celebrate the king’s survival with bonfires, so long as they were without any danger or disorder. This made 1605 the first year the plot’s failure was celebrated.

The following January, days before the surviving conspirators were executed, Parliament, at the initiation of James I, passed the Observance of 5th November Act, commonly known as the Thanksgiving Act. It was proposed by a Puritan Member of Parliament, Edward Montagu, who suggested that the king’s apparent deliverance by divine intervention deserved some measure of official recognition, and kept the 5th of November free as a day of thanksgiving while in theory making attendance at Church mandatory. A new form of service was also added to the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, for use on that date. Little is known about the earliest celebrations. In settlements such as Carlisle, Norwich, and Nottingham, corporations (town governments) provided music and artillery salutes. Canterbury celebrated the 5th of November, 1607 with 106 pounds (48 kg) of gunpowder and 14 pounds (6.4 kg) of match, and three years later food and drink were provided for local dignitaries, as well as music, explosions, and a parade by the local militia. Even less is known of how the occasion was first commemorated by the general public, although records indicate that in the Protestant stronghold of Dorchester a sermon was read, the church bells rung, and bonfires and fireworks lit.

A Guy Fawkes wax model being burned on a bonfire.

This was at the Billericay Fireworks Spectacular in Lake Meadows Park, Billericay, Essex, England.

Guy Fawkes on Bonfire Night, 2016.

This is a Guy Fawkes I made for a bonfire I had when I was living in my house in Kitts, Green, Birmingham, England. It isn’t as spectacular as the one above and it could have been better but it was a last-minute project made in around two hours. He was held together by duct tape, sellotape and safety pins but he looked cool in his cardboard V for Vendetta mask and his Wii remote lightsaber (he was a modern-day Guy who loves Sci-Fi) ha ha.

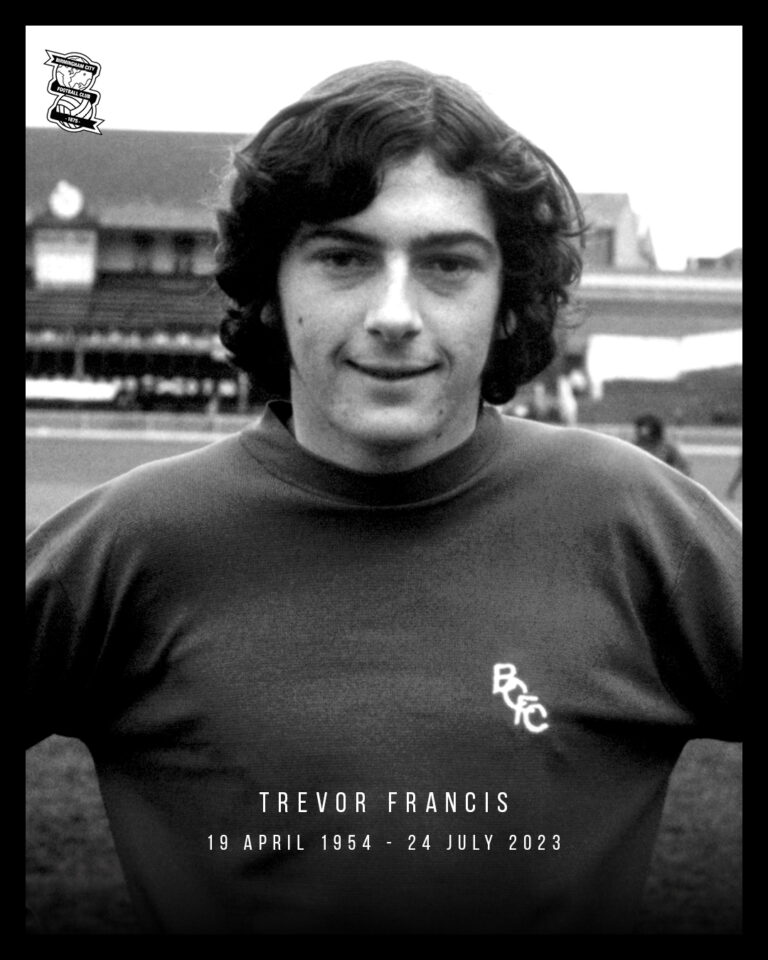

A Guy Fawkes mask from Whoopee! dated 28/10/1978.

There have been a few masks printed of Guy Fawkes in the comic Whoopee!, my favourite in the 1970’s and 1980’s, but this one is the one that I used for a family-made Guy in the 70’s.

Read about Whoopee! and lots of great old comics from my childhood here.

Early Significance

According to historian and author Antonia Fraser, a study of the earliest sermons preached demonstrates an anti-Catholic concentration mystical in its fervour. Delivering one of five 5th of November sermons printed in A Mappe of Rome in 1612, Thomas Taylor said that Fawkes’s cruelty had been almost without bounds. Such messages were also spread in printed works such as Francis Herring’s Pietas Pontifica (republished in 1610 as Popish Piety), and John Rhode’s A Brief Summe of the Treason intended against the King & State. By the 1620’s the Fifth was honoured in market towns and villages across the country, though it was some years before it was commemorated throughout England. Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was then known, became the predominant English state commemoration. Some parishes made the day a festive occasion, with public drinking and solemn processions. Concerned though about James’s pro-Spanish foreign policy, the decline of international Protestantism, and Catholicism in general, Protestant clergymen who recognised the day’s significance called for more dignified and profound thanksgivings each November the 5th.

What unity English Protestants had shared in the plot’s immediate aftermath began to fade when in 1625 James’s son, the future Charles I, married the Catholic Henrietta Maria of France. Puritans reacted to the marriage by issuing a new prayer to warn against rebellion and Catholicism, and on the 5th of November that year, effigies of the pope and the devil were burnt, the earliest such report of this practice and the beginning of centuries of tradition. During Charles’s reign, Gunpowder Treason Day became increasingly partisan. Between 1629 and 1640 he ruled without Parliament, and he seemed to support Arminianism, regarded by Puritans such as Henry Burton as a step toward Catholicism. By 1636, under the leadership of the Arminian Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud, the English church was trying to use November the 5th to denounce all seditious practices, and not just popery. Puritans went on the defensive, some pressing for further reformation of the Church.

Bonfire Night assumed a new fervour during the events leading up to the English Interregnum. Although Royalists disputed their interpretations, Parliamentarians began to uncover or fear new Catholic plots. Preaching before the House of Commons on the 5th of November 1644, Charles Herle claimed that Papists were tunnelling “from Oxford, Rome, Hell, to Westminster, and there to blow up, if possible, the better foundations of your houses, their liberties and privileges”.

Following Charles I’s execution in 1649, the country’s new republican regime remained undecided on how to treat November the 5th. Unlike the old system of religious feasts and State anniversaries, it survived, but as a celebration of parliamentary government and Protestantism, and not of monarchy. Commonly the day was still marked by bonfires and miniature explosives, but formal celebrations resumed only with the Restoration, when Charles II became king. Courtiers, High Anglicans and Tories followed the official line. Generally, the celebrations became more diverse. By 1670 London apprentices had turned the 5th of November into a fire festival, attacking not only popery but also sobriety and good order, demanding money from coach occupants for alcohol and bonfires. The burning of effigies, largely unknown to the Jacobeans, continued in 1673 when Charles’s brother, the Duke of York, converted to Catholicism. In response, accompanied by a procession of about 1,000 people, the apprentices fired an effigy of the Whore of Babylon, bedecked with a range of papal symbols. Similar scenes occurred over the following few years. On the 17th of November 1677, anti-Catholic fervour saw the Accession Day marked by the burning of a large effigy of the pope (his belly was filled with live cats) and two effigies of devils whispering in his ear. Two years later, as the exclusion crisis reached its zenith, an observer noted that the 5th at night, being gunpowder treason, there were as many bonfires and burning of popes as had ever been seen. Violent scenes in 1682 forced London’s militia into action, and to prevent any repetition the following year a proclamation was issued, banning bonfires and fireworks.

Fireworks were also banned under James II (previously the Duke of York), who became king in 1685. Attempts by the government to tone down Gunpowder Treason Day celebrations were, however, largely unsuccessful, and some reacted to a ban on bonfires in London (born from a fear of more burnings of the pope’s effigy) by placing candles in their windows as a witness against Catholicism. When James was deposed in 1688 by William of Orange – who, importantly, landed in England on November the 5th and the day’s events turned also to the celebration of freedom and religion, with elements of anti-Jacobitism. While the earlier ban on bonfires was politically motivated, a ban on fireworks was maintained for safety reasons.

Guy Fawkes Day

William III’s birthday fell on the 4th of November, and for an orthodox Whig, the two days therefore became an important double anniversary. William ordered that the Thanksgiving service for the 5th of November be amended to include thanks for his “happy arrival” and “the Deliverance of our Church and Nation”. In the 1690’s he re-established Protestant rule in Ireland, and the Fifth, occasionally marked by the ringing of church bells and civic dinners was consequently eclipsed by his birthday commemorations. From the 19th century, November the 5th celebrations there became sectarian in nature. Its celebration in Northern Ireland remains controversial, unlike in Scotland where bonfires continue to be lit in various cities. In England though, as one of 49 official holidays, for the ruling class, the 5th of November became overshadowed by events such as the birthdays of Admiral Edward Vernon, or John Wilkes, and under George II and George III, with the exception of the Jacobite Rising of 1745, it was largely a polite entertainment rather than an occasion for vitriolic thanksgiving. For the lower classes, however, the anniversary was a chance to pit disorder against order, a pretext for violence and uncontrolled revelry. In 1790 newspaper The Times reported instances of children begging for money for Guy Fawkes.

Lower-class rioting continued, with reports in Lewes of annual rioting, intimidation of respectable householders and the rolling through the streets of lit tar barrels. In Guildford, gangs of revellers who called themselves guys terrorised the local population. Proceedings were concerned more with the settling of old arguments and general mayhem, than any historical reminiscences. Similar problems arose in Exeter, originally the scene of more traditional celebrations. In 1831 an effigy was burnt of the new Bishop of Exeter Henry Phillpotts, a High Church Anglican and High Tory who opposed Parliamentary reform, and who was also suspected of being involved in creeping popery. A local ban on fireworks in 1843 was largely ignored, and attempts by the authorities to suppress the celebrations resulted in violent protests and several injured constables.

On several occasions during the 19th century, The Times also reported that the tradition was in decline. Civil unrest brought about by the union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland in 1800 resulted in Parliament passing the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, which afforded Catholics greater civil rights, continuing the process of Catholic Emancipation in the two kingdoms. The traditional denunciations of Catholicism had been in decline since the early 18th century and were thought by many, including Queen Victoria, to be outdated, but the pope’s restoration in 1850 of the English Catholic hierarchy gave renewed significance to November the 5th, as demonstrated by the burnings of effigies of the new Catholic Archbishop of Westminster Nicholas Wiseman, and the pope. At Farringdon Market 14 effigies were processed from the Strand and over Westminster Bridge to Southwark, while extensive demonstrations were held throughout the suburbs of London. Effigies of the 12 new English Catholic bishops were paraded through Exeter, already the scene of severe public disorder on each anniversary of the Fifth. Gradually, however, such scenes became less popular. With little resistance in Parliament, the thanksgiving prayer of November the 5th contained in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer was abolished, and in March 1859 the Anniversary Days Observance Act repealed the Observance of 5th November Act.

As the authorities dealt with the worst excesses, public decorum was gradually restored. The sale of fireworks was restricted, and the Guildford guys were neutralised in 1865, although this was too late for one constable, who died of his wounds. Violence continued in Exeter for some years, peaking in 1867 when incensed by rising food prices and banned from firing their customary bonfire, a mob was twice in one night driven from Cathedral Close by armed infantry. Further riots occurred in 1879, but there were no more bonfires in Cathedral Close after 1894. Elsewhere, sporadic instances of public disorder persisted late into the 20th century, accompanied by large numbers of firework-related accidents, but a national Firework Code and improved public safety have in most cases brought an end to such things.

Lewes Bonfire Night in 2010.

Revellers in East Sussex, England.

The Guy Fawkes of 1850.

This commentary on the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in England, in 1850 is from Punch magazine, November of that year. The artist is unknown.

Songs, Guys And Later Developments

One notable aspect of the Victorians’ commemoration of Guy Fawkes Night was its move away from the centres of communities to their margins. Gathering wood for the bonfire increasingly became the province of working-class children, who solicited combustible materials, money, food and drink from wealthier neighbours, often with the aid of songs. Most opened with the familiar “Remember, remember, the fifth of November, Gunpowder Treason and Plot”. The earliest recorded rhyme, from 1742, is reproduced below alongside one bearing similarities to most Guy Fawkes Night ditties, recorded in 1903 at Charlton on Otmoor.

From 1742:

“Don’t you Remember,

The Fifth of November,

‘Twas Gunpowder Treason Day,

I let off my gun,

And made’em all run.

And Stole all their Bonfire away.”

From 1903:

“The fifth of November, since I can remember,

Was Guy Faux, Poke him in the eye,

Shove him up the chimney pot, and there let him die.

A stick and a stake, for King George’s sake,

If you don’t give me one, I’ll take two,

The better for me, and the worse for you,

Ricket-a-racket your hedges shall go.”

Organised entertainment also became popular in the late 19th century, and 20th-century pyrotechnic manufacturers renamed Guy Fawkes Day as Firework Night. Sales of fireworks dwindled somewhat during the First World War but resumed in the following peace. At the start of the Second World War, celebrations were again suspended, resuming in November 1945. For many families, Bonfire Night became a domestic celebration, and children often congregated on street corners, accompanied by their own effigy of Guy Fawkes. This was sometimes ornately dressed and sometimes a barely recognisable bundle of rags stuffed with whatever filling was suitable. A survey found that in 1981 about 23 per cent of Sheffield schoolchildren made Guys, sometimes weeks before the event. Collecting money was a popular reason for their creation, the children taking their effigy from door to door or displaying it on street corners. But mainly, they were built to go on the bonfire, itself sometimes comprising wood stolen from other pyres that helped bolster another November tradition, Mischief Night. Rival gangs competed to see who could build the largest, sometimes even burning the wood collected by their opponents In 1954 the Yorkshire Post reported on fires late in September, a situation that forced the authorities to remove latent piles of wood for safety reasons. Lately, however, the custom of a penny for the Guy has almost completely disappeared. In contrast, some older customs still survive. In Ottery St. Mary residents run through the streets carrying flaming tar barrels, and since 1679 Lewes has been the setting of some of England’s most extravagant November the 5th celebrations, the Lewes Bonfire.

Generally, modern November the 5th celebrations are run by local charities and other organisations, with paid admission and controlled access. In 1998 an editorial in the Catholic Herald called for the end of Bonfire Night, labelling it an offensive act. Author Martin Kettle, writing in The Guardian in 2003, bemoaned an occasionally nannyish attitude to fireworks that discourages people from holding firework displays in their back gardens, and an unduly sensitive attitude toward the anti-Catholic sentiment once so prominent on Bonfire Night. David Cressy summarised the modern celebration with these words, “The rockets go higher and burn with more colour, but they have less and less to do with memories of the Fifth of November … it might be observed that Guy Fawkes’ Day is finally declining, having lost its connection with politics and religion. But we have heard that many times before.”

In 2012 Tom de Castella said, “It’s probably not a case of Bonfire Night decline, but rather a shift in priorities… there are new trends in the bonfire ritual. Guy Fawkes masks have proved popular and some of the more quirky bonfire societies have replaced the Guy with effigies of celebrities in the news (including Lance Armstrong and Mario Balotelli) and even politicians. The emphasis has moved. The bonfire with a Guy on top (indeed the whole story of the Gunpowder Plot) has been marginalised. But the spectacle remains.

Children from Bontnewydd collecting for the Guy.

This photo by Geoff Charles of children in Caernarfon, Wales was taken in November 1962. The sign reads Penny for the Guy in Welsh.

Spectators around a Bonfire at Himley Hall.

This photo was taken by Sam Roberts in Dudley, England.

In Other Countries

Gunpowder Treason Day was exported by settlers to colonies around the world, including members of the Commonwealth of Nations such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and various Caribbean nations. In Australia, Sydney (founded as a British penal colony in 1788) saw at least one instance of the parading and burning of a Guy Fawkes effigy in 1805, while in 1833, four years after its founding, Perth listed Gunpowder Treason Day as a public holiday. By the 1970’s, Bonfire Night had become less common in Australia, with the event simply an occasion to set off fireworks with little connection to Guy Fawkes. Mostly they were set off annually on a night called cracker night which would include the lighting of bonfires. Some states had their fireworks night or cracker night at different times of the year, with some being let off on the 5th of November, but most often, they were let off on the Queen’s birthday. After a range of injuries to children involving fireworks, Fireworks nights and the sale of fireworks were banned in all states except the Australian Capital Territory by the early 1980’s, which saw the end of cracker night.

Some measure of celebration remains in New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa. On the Cape Flats in Cape Town, South Africa, Guy Fawkes Day has become associated with youth hooliganism. In Canada in the 21st century, celebrations of Bonfire Night on November the 5th are largely confined to the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. The day is still marked in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and in Saint Kitts and Nevis, but a fireworks ban by Antigua and Barbuda during the 1990’s reduced its popularity in that country.

In North America, the commemoration was at first paid scant attention, but the arrest of two boys caught lighting bonfires on the 5th of November 1662 in Boston suggests, in historian James Sharpe’s view, that an underground tradition of commemorating the Fifth existed. In parts of North America, it was known as Pope Night, celebrated mainly in colonial New England, but also as far south as Charleston. In Boston, founded in 1630 by Puritan settlers, an early celebration was held in 1685, the same year that James II assumed the throne. Fifty years later, again in Boston, a local minister wrote about a great number of people going to Dorchester where at night they made a Great Bonfire and plaid off many fireworks. The day ended in tragedy when four young men coming home in a Canoe were all Drowned. Ten years later the raucous celebrations were the cause of considerable annoyance to the upper classes and a special Riot Act was passed, to prevent riotous tumultuous and disorderly assemblies of more than three persons, all or any of them armed with Sticks, Clubs or any kind of weapons, or disguised with vizards, or painted or discoloured faces, or in any manner disguised, having any kind of imagery or pageantry, in any street, lane, or place in Boston. With inadequate resources, however, Boston’s authorities were powerless to enforce the Act. In the 1740’s gang violence became common, with groups of Boston residents battling for the honour of burning the pope’s effigy. But by the mid-1760’s these riots had subsided, and as colonial America moved towards revolution, the class rivalries featured during Pope Day gave way to anti-British sentiment. Author Alfred Young said Pope Day provided the scaffolding, symbolism, and leadership for resistance to the Stamp Act in 1764–65, forgoing previous gang rivalries in favour of a unified resistance to Britain.

The passage in 1774 of the Quebec Act, which guaranteed French Canadians free practice of Catholicism in the Province of Quebec, provoked complaints from some Americans that the British were introducing Popish principles and French law. Such fears were bolstered by opposition from the Church in Europe to American independence, threatening a revival of Pope Day.

The tradition continued in Salem as late as 1817, and was still observed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1892. In the late 18th century, effigies of prominent figures such as two Prime Ministers of Great Britain, the Earl of Bute and Lord North, and the American traitor General Benedict Arnold, were also burnt. In the 1880’s bonfires were still being lit in some New England coastal towns, although no longer to commemorate the failure of the Gunpowder Plot. In the area around New York City, stacks of barrels were burnt on Election Day eve, which after 1845 was a Tuesday early in November.

See Also

Blog Posts

Links

The image above of Guy Fawkes on Bonfire Night, 2016 is copyright of Frank Parker.

The image above of the festivities in Windsor Castle during Guy Fawkes night in 1776 is copyright of Wikipedia user William Warby. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 2.0).

A Guy Fawkes mask from Whoopee! dated 28/10/1978 is by artist Brian Walker. It comes from the website Great News For All Readers!

The image above of Lewes Bonfire Night in 2010 is copyright of Wikipedia user Heather Buckley. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 2.0).

The image above of the Guy Fawkes of 1850 is by artist unknown. It is in the Public Domain.

The image above of Children from Bontnewydd collecting for the Guy is by Geoff Charles. It is in the Public Domain.

The image above of spectators around a Bonfire at Himley Hall is by Sam Roberts. It comes with a Creative Commons licence (CC BY 2.0).

Great News For All Readers! – Official website. This website is from a collector of comics published in Britain in the 1970’s and 1980’s. It shows his memories of being a reader of these comics as a child, his observations as a collector today and an attempt to catalogue the comics from a fan’s perspective.

Great News For All Readers! on Facebook.

Great News For All Readers! on Twitter.

Creative Commons – Official website. They offer better sharing, advancing universal access to knowledge and culture, and fostering creativity, innovation, and collaboration.