There is only one team in Birmingham worth supporting with true passion and Birmingham City is it. I have been supporting them since 1978 when Jim Smith was the manager. He is my favourite manager to date. I am a blue nose ’til I die.

You can read lots more about Blues by clicking here.

Below you will find interviews etc. regarding Blues for September 2024 of the 2024/25 season. You can see all the months in full here.

October 2024

Birmingham City 1 – Huddersfield Town 0: Chris Davies Interview.

On the 1st of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about our SEVENTH win in a row, after Alfie May’s goal helped us see off The Terriers 1 – 0 at St. Andrew’s.

Birmingham City 1 – Huddersfield Town 0: Alfie May Interview.

On the 1st of October, 2024, Alfie May spoke to Blues T.V. about scoring his fifth goal of the season, ensuring we made it SEVEN WINS out of seven.

Birmingham City 1 – Huddersfield Town 0: Match Highlights.

Extended highlights of our 1 – 0 win over Huddersfield Town at St. Andrew’s, as Alfie May’s close-range finish made it SEVEN wins in a row.

Charlton Athletic 1 – Birmingham City 0: Chris Davies Interview.

On the 5th of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about our first league defeat of the season at the hands of Charlton Athletic.

Charlton Athletic 1 – Birmingham City 0: Alex Cochrane Interview.

On the 5th of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about the 1 – 0 loss to Charlton Athletic.

Charlton Athletic 1 – Birmingham City 0: Match Highlights.

Highlights of our trip to The Valley where we fell to our first defeat of the season.

Paik Seung-Ho’s Interview With Blues T.V.

On the 7th of October, 2024, Birmingham City midfielder Paik Seung-Ho sat down with Blues T.V. to talk about signing a contract extension to keep him at Blues until at least June 2028.

This is great news.

Shrewsbury Town 0 – Birmingham City 4: Chris Davies Interview.

On the 8th of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about witnessing his side deliver an impressive 4 – 0 victory over Shrewsbury Town in the E.F.L. Trophy.

Shrewsbury Town 0 – Birmingham City 4: Scott Wright Interview.

On the 8th of October, 2024, Scott Wright spoke to Blues T.V. about scoring two and assisting one in our 4 – 0 victory over Shrewsbury Town in the E.F.L. Trophy.

Shrewsbury Town 0 – Birmingham City 4: Match Highlights.

Extended highlights of our 4 – 0 win over Shrewsbury Town at Croud Meadow, as a double from Scott Wright helped us to a crucial three points in the E.F.L. Trophy.

Keshi Anderson’s Interview With Blues T.V.

On the 9th of October, 2024, Birmingham City midfielder Keshi Anderson sat down with Blues T.V. to talk about signing a contract extension to secure his future to the Club until at least June 2026.

This is great news.

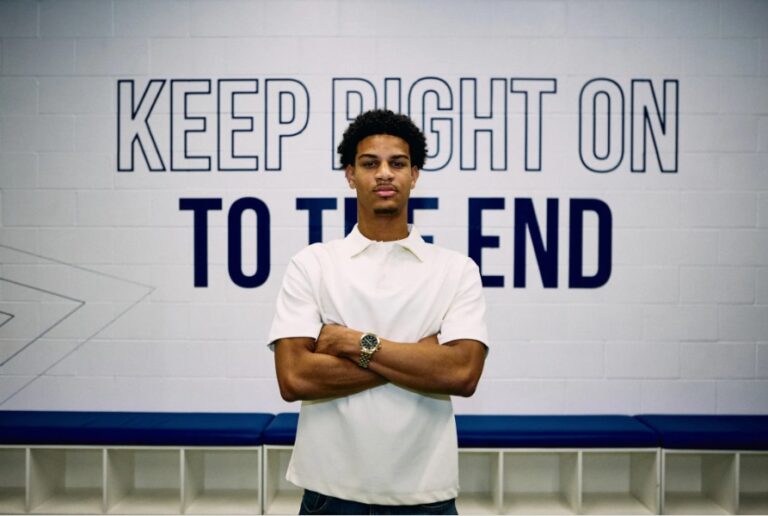

Ethan Laird’s Interview With Blues T.V.

On the 11th of October, 2024, Birmingham City defender Ethan Laird sat down with Blues T.V. to talk about his delight at signing a contract extension with the Club, until at least June 2028.

This is great news and a great interview. I like Ethan and his cheerful personality a lot. Playing first-team football or not he is an important man to have at the club to boost morale and lift people up.

Lincoln City 1 – Birmingham City 3: Chris Davies Interview.

On the 19th of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about our impressive victory over Lincoln City, cementing our place at the top of League One.

Lincoln City 1 – Birmingham City 3: Ryan Allsop Interview.

On the 19th of October, 2024, Ryan Allsop spoke to Blues T.V. about how his penalty-saving heroics helped us to a 3 -1 victory over Lincoln City.

Lincoln City 1 – Birmingham City 3: Match Highlights.

Extended highlights of our 3 – 1 win over Lincoln City, which included a double for Keshi Anderson and another goal for Willum Willumsson.

Birmingham City 2 – Bolton Wanderers 0: Chris Davies Interview.

On the 22nd of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about our impressive 2 – 0 victory over Bolton Wanderers, keeping us at the summit of Sky Bet League One.

Birmingham City 2 – Bolton Wanderers 0: Ben Davies Interview.

On the 22nd of October, 2024, Ben Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about another impressive individual and team performance, after goals from Tomoki Iwata and Jay Stansfield kept us at the summit of League One.

Birmingham City 2 – Bolton Wanderers 0: Match Highlights.

Extended highlights of our comprehensive 2 – 0 victory over Bolton Wanderers, courtesy of goals from Tomoki Iwata and Jay Stansfield.

Mansfield Town 1 – Birmingham City 1: Chris Davies Interview.

On the 26th of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about our 1 – 1 draw with Mansfield Town, after a strike from Willum Willumsson was cancelled out by Mansfield’s free-kick.

Mansfield Town 1 – Birmingham City 1: Willum Willumsson Interview.

On the 26th of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about scoring his fourth goal of the season in our 1 – 1 draw with Mansfield Town.

Mansfield Town 1 – Birmingham City 1: Match Highlights.

Extended highlights of our 1 – 1 draw with Mansfield Town in League One, with Willum Willumsson’s fourth goal of the season not enough to secure all three points for Birmingham City.

Birmingham City 7 – Fulham Under-21’s 1: Chris Davies Interview.

On the 29th of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about our 7 – 1 victory over Fulham Under-21’s in the E.F.L. Trophy Southern Section Group A, courtesy of goals from nearly half the team.

Birmingham City 7 – Fulham Under-21’s 1: Marc Leonard Interview.

On the 29th of October, 2024, Chris Davies spoke to Blues T.V. about our resounding 7-1 victory over Fulham Under-21’s in the E.F.L. Trophy Southern Section Group A.

Birmingham City 7 – Fulham Under-21’s 1: Match Highlights.

Highlights of our 7 – 1 win over Fulham Under-21’s in the E.F.L. Trophy Southern Section Group A.

All Other Videos For The 2024/25 Season

Blog Posts

Birmingham City: Blues History.

Birmingham City: First Team Squad For The 2024/25 Season.

Birmingham City: Fixtures, Results And Goal Scorers For The 2024/25 Season.

Birmingham City: Kits For The 2024/25 Season.

Birmingham City: News For The 2024/25 Season.

Birmingham City: Our 2023/24 Season In Review.

Birmingham City: Staff For The 2024/25 Season.

Birmingham City: The 2023/24 Season Archive.

Birmingham City: Trevor Francis.

Notes And Links

The Birmingham City Club logo shown at the top of this page is the copyright of Birmingham City F.C. and came from their social media pages.

Birmingham City F.C. – Official website.

Birmingham City on Facebook – Official Facebook page.

Birmingham City on Twitter – Official Twitter page.

Birmingham City on Instagram – Official Instagram page.

Birmingham City on YouTube – Official YouTube page.

Blues Store – Official club store website.

Birmingham City Foundation – Official website.

Nike – Official website.

Undefeated – Official website.