On Monday the 22nd of September, 2025, I joined Advance UK. I did this because I TRULY believe Ben Habib and his newly formed political party are our only hope of saving this country from the evil, fascist and oppressive control it is currently under. If you value any kind of freedom of speech, are, as in my case, PROUD TO BE ENGLISH and you want to put the GREAT back in Great Britain and be able to show your pride in flying whatever flag you like without being called a racist, or this phobic or that phobic, then click here via my recruiter page (at the bottom) to join TODAY!

I myself am not religious, but there is no doubt this country is a Christian country built on Christian/Family values, and it should, under no circumstances, be allowed to be changed from that way, FOR ANYONE!

Read all about Ben and the party below.

Introducing Advance UK.

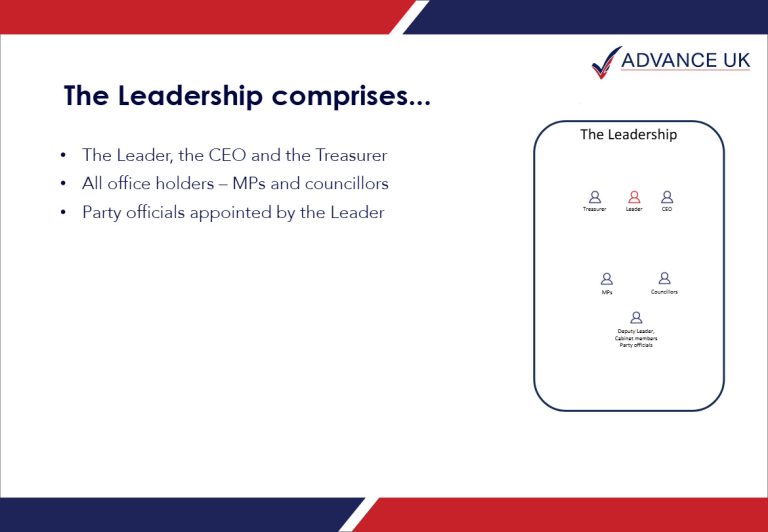

The Leadership

The Leadership Comrises.

The Leadership manage the party, lead campaign strategies, oversee branch activities and participate in policy making and candidate selection.

The Leader

The Leader.

Ben Habib

Ben Habib, Leader Of Advance UK.

A Voice For Courage And Conviction

Ben Habib is the Leader of Advance UK. A formidable businessman, seasoned politician, and steadfast advocate for Britain’s independence, prosperity, and national pride. He stands at the forefront of a movement to reclaim sovereignty and restore confidence in our democracy.

Born in Karachi to a Pakistani father and British mother, Ben moved to the UK at 13. He went on to become Head of Rugby School, before studying Natural Sciences at Cambridge University, where he also earned a Boxing Blue.

His early career was in finance in the City, before moving into private property development and investment in 1994. He went on to found First Property Group plc, an FCA-regulated and London Stock Exchange-listed fund manager, where he continues to serve as Chief Executive.

Ben entered politics in 2019, joining the Brexit Party in response to Theresa May’s failure to deliver Brexit. He was elected a Member of the European Parliament and later became Deputy Leader of Reform UK. Known for his principled opposition to the Northern Ireland Protocol, he has consistently fought to defend Britain’s sovereignty and independence.

He joined Reform UK in March 2023, becoming Deputy Leader later that year and helping take the party from 6% to 16% in the polls. He later resigned over disagreements on governance and political principles.

In June 2025, he founded Advance UK, which has grown at a remarkable pace, gaining over 30,000 members in just two months and becoming the seventh-largest party in the UK. Its growth continues.

As leader, Ben is determined to recruit the finest minds and most capable people in the country to deliver a proud, sovereign, and prosperous United Kingdom once again.

“I love my country, I love you, and I will not falter. I will deliver for you.”

Mission

Help Us Mend Broken Britain.

We will build a proud, independent and prosperous United Kingdom.

We stand for nation, freedom, democracy and equality under the law.

Nation

Our Nation is the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, in all its parts and with all its people.

The Party asserts every part of the Acts of Union which created the Nation. The Party stands against any arrangement which is not compliant with those Acts.

The Party promotes and celebrates the Nation’s Christian constitution, roots, traditions, culture, and values.

The sovereignty of the Nation stands as a bulwark against the undemocratic influence of supra-national institutions and international law.

Freedom Of Speech

A cornerstone of democracy is the freedom of speech.

All people should be free to think, speak and act according to their conscience and beliefs if they do not incite violence.

Children should be protected from ideological and political indoctrination.

There should be minimal Government intervention in people’s lives.

Democracy

The Government should serve the British people and be accountable to them.

There can be no dilution of the Government’s ability to discharge this obligation, and the people’s ability to hold them to account, by membership of international bodies, the entering into of international treaties, international law and domestic quangos.

There should be minimal Government intervention in people’s lives.

Equality Under The U.K. Law

All people living in the UK should be equal before and subject only to UK law.

All people should be able to live free from the threat of terror or violent crime and without prejudice.

There should be no discrimination based on ethnicity, sex or sexual orientation.

The British legal system must be the only legal system in the Nation and its application must be impartial and free of political influence or control.

Security of life and property are fundamental in creating a peaceful and prosperous society.

Our Mission Statement

Our Mission Statement.

Structure

How We Will Work Together.

Information.

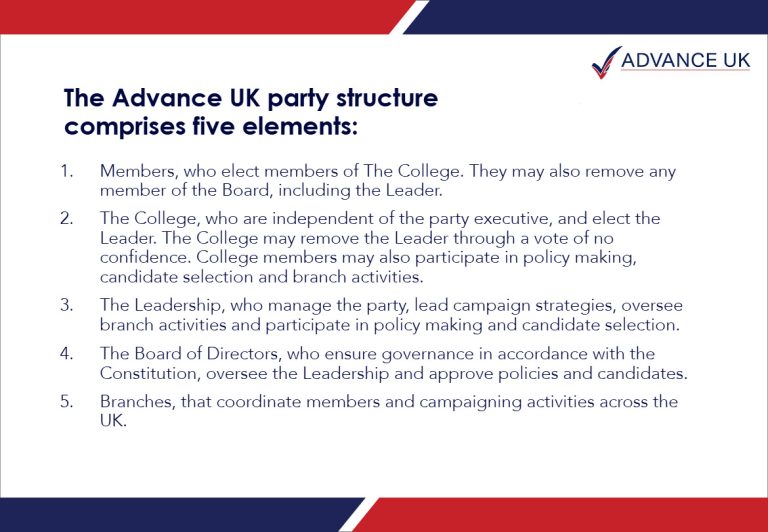

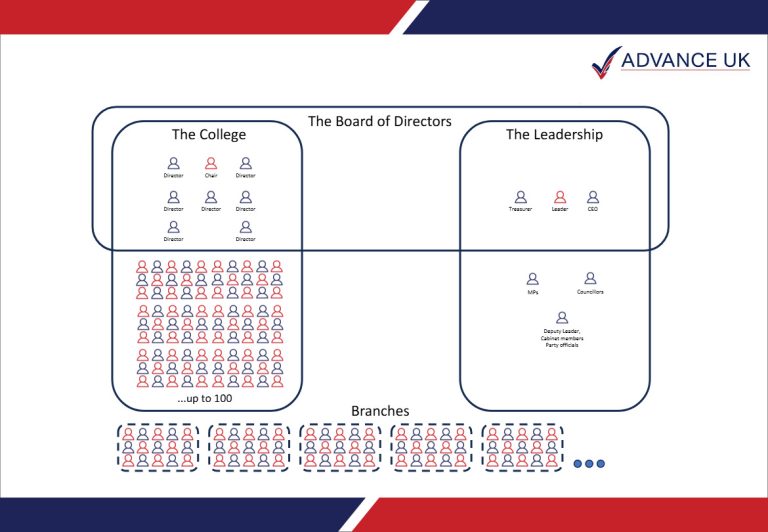

The Advance UK party structure comprises five elements.

Members

Members And Branches.

Members elect members of The College. They may also remove any member of the Board, including the Leader.

Members of the Party will, subject to due process, be eligible to:

Receive notices and communications.

Attend members’ meetings.

Stand for election to the College.

Join the Party executive.

Stand as candidates in local and national elections.

Join local associations.

Campaign for the Party.

By a simple majority, vote in the election of College members.

By a simple majority, vote to remove directors of the Party (including the leader).

Become A Member

You can join via my recruiter page (at the bottom) by clicking here.

The College

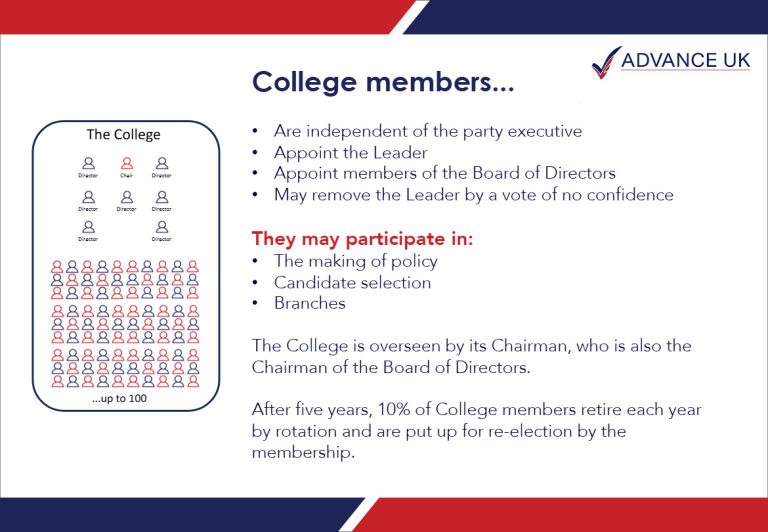

The College are independent of the party executive, and elect the Leader. The College may remove the Leader through a vote of no confidence. College members may also participate in policy making, candidate selection and branch activities.

The College is overseen by its Chairman, who is also the Chairman of the Board of Directors. After five years, 10% of College members retire each year by rotation and are put up for re-election by the membership.

College Members

College Members.

Craig Walton

Craig Walton.

Read more about Craig here.

gavin Maxwell

Gavin Maxwell.

Read more about Gavin here.

nick buckley

Nick Buckley.

Read more about Nick here.

richard thompson

Richard Thompson.

Read more about Richard here.

Bepi Pezzulii

Bepi Pezzulii.

Read more about Bepi here.

justin downes

Justin Downes.

Read more about Justin here.

andrew cadman

Andrew Cadman.

Read more about Andrew here.

paul thorpe

Paul Thorpe.

Read more about Paul here.

aileen quinton

Aileen Quinton.

Read more about Aileen here.

norman fenton

Norman Fenton.

Read more about Norman here.

howard cox

Howard Cox.

Read more about Howard here.

paul burgess

Read more about Paul here.

Paul Burgess.

richie taylor

Richie Taylor.

Read more about Richie here.

katie waissel

Katie Waissel.

Read more about Katie here.

jim ferguson

Jim Ferguson.

Read more about Jim here.

kathy gyngell

Read more about Kathy here.

Kathy Gyngell.

The Board Of Directors

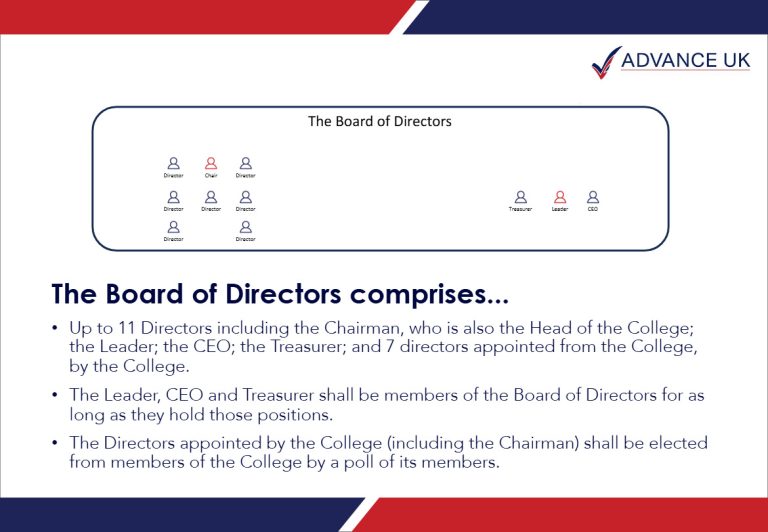

The Board Of Directors Comprises.

The Board Of Directors.

The Board of Directors ensure governance in accordance with the Constitution, oversee the Leadership and approve policies and candidates.

Branches

Branches coordinate members and campaigning activities across the U.K.

Information.

Get In Touch With Advance UK

General Enquiries

If you are an Advance UK member or supporter, or you have questions or feedback about our work, please get in touch using the form here. You may also find the answer to your question in the Frequently Asked Question’s below.

Press Enquiries

If you are a member of the press, and you have questions about Advance UK, please email our press office by clicking here.

Frequently Asked Questions

Click here to see any F.A.Q.’s for Advance UK.

Events

To see all of Advance UK’s events, click here.

JOIN TODAY!

If you are tired of being lied to and treated like a stranger in your own country, and you want a government that will TRULY care about its citizens, then you can join Advance UK via my recruiter page (at the bottom) by clicking here and help grow our party that will become second to none.

Blog Posts

Notes And Links

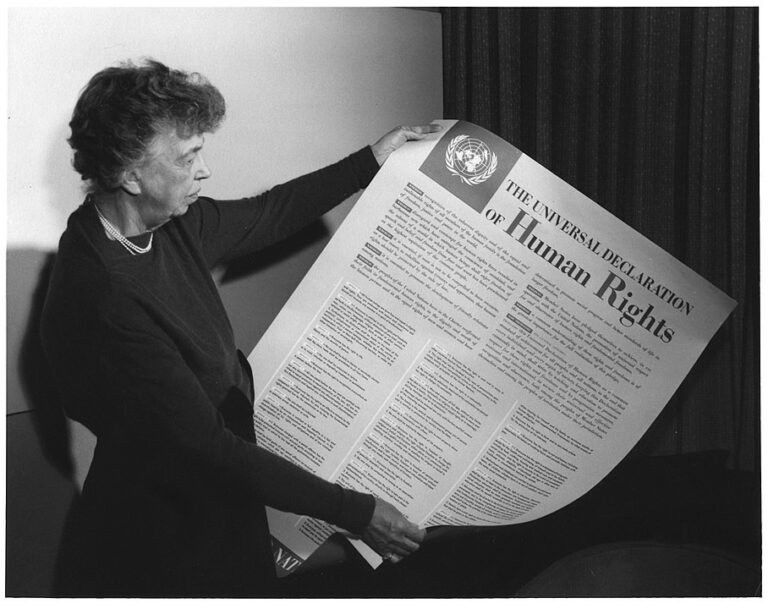

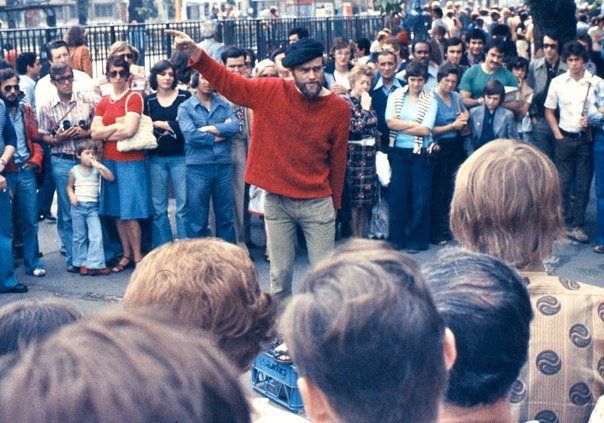

The image shown at the top of this page, and subsequent photos, are the copyright of Advance UK.

Advance UK – Official website.

Advance UK on Facebook – This is their official Facebook page.

Advance UK on X – This is their official X page.

Advance UK on Instagram – This is their official Instagram page.

Advance UK on YouTube – This is their official YouTube page.

Ben Habib on Facebook – This is his official Facebook page.

Ben Habib on X – This is his official X page.

Ben Habib on Instagram – This is his official Instagram page.

Ben Habib on YouTube – This is his official YouTube page.